In the Eye of a Cyclone

When about two weeks ago I was flying to Berlin via a roundabout route, black clouds of war were already gathering over Europe. That day, however, my attention was completely focused on the storm Eunice and on the fear that it might thwart my reviewing plans. I got to Berlin safely and before going to the first performance I had a discussion with my Berlin friends, during which we made various predictions – all of them wrong, as it later turned out – about the course of events beyond Poland’s eastern border. Unease was growing, but for the time being I was looking forward to two Wagner performances at the Deutsche Oper, performances of productions which had been in the company’s repertoire for quite some time, but which, strangely enough, I had not had the opportunity to see before.

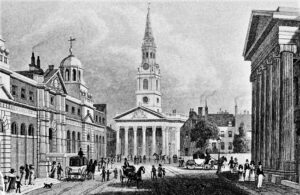

Both originated at a unique moment in the company’s history. Tannhäuser, directed by Kirsten Harms, was premiered in 2008, more or less half way through her management of the company – two years after the famous scandal with the suspension of Hans Neuenfels’ staging of Idomeneo, following signals from the police and the Home Office that the epilogue added by Neuenfels and featuring the severed heads of Poseidon, Buddha, Christ and Mohammed could provoke serious unrest in the city. As a result of this unprecedented act of censorship the theatre came under severe criticism, which soon, however, abated following a change of the fateful decision and Harms’ numerous subsequent achievements as a manager and artist. During her tenure the Deutsche Oper saw both the attendance and its income rise, with the company’s repertoire expanding to include a number of musical rarities and works of composers who had been silenced by history. After Harms’ departure the company experienced an interregnum of more than a year, the final phase of which was marked by the premiere of Lohengrin in April 2012, shortly before Dietmar Schwarz took over as General Manager. The production was directed by Kasper Holten, the newly appointed Director of Opera at the Royal Opera House in London.

Tannhäuser, Act 2. Photo: Bettina Stöß

In the first few seasons of its stage existence it was Harms’ Tannhäuser that received much more favourable reviews. Holten’s Lohengrin had to face comparisons with the legend of Götz Friedrich’s 1990 concept – so beloved by the Berlin audience – and lost the first round. However, time proved kinder to Lohengrin, a production not without some faults, but nevertheless coherent and drawing attention to unsettling aspects of the story – perhaps unjustly neglected by the earlier directors.

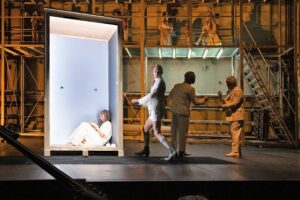

The minimalistic and fairly conventional Tannhäuser offends primarily by its lack of any axis keeping the narrative together. The only trope that seems to lead anywhere – in line with the composer’s intention, it has to be said – is the combination of the figure of Venus and Elisabeth into one, also one singer. Yet in Harms’ interpretation nothing comes out of this. The conflict is not resolved, the scales do not turn the favour of either side of the female nature; even in the finale it remains unclear whose image Tannhäuser has in mind as he is dying and whether he is dying in the first place – perhaps he is just waking up from nightmares tormenting both the protagonist and the audience in equal measure. The whole poetry of theatre disappears after the first scene, in which an armour-clad supernumerary plunges slowly into the abyss of Venus’ grotto. After that there are only images, some spectacular (sets, lighting and costumes by Bernd Damovsky), but, to put it mildly, loosely linked to the action, the libretto and the score. Why is the pilgrims’ chorus in Act I roasting in hell, surrounded by a pack of demons straight from Gustave Doré’s illustrations to Milton’s Paradise Lost? Why in Act III do all the pilgrims end up in a field hospital, as if the pilgrimage to Rome has been clearly harmful to them? Why does the song contest in Act II look like a cross between Terry Gilliam’s Jabberwocky and animated miniatures from the Codex Manesse? I am not judging the ideas in themselves – the could have certainly been enacted on stage brilliantly, if only the director had had any sense of humour and distance from the matter of the work. I also have the impression that the technical team were not convinced by Harms’ concept either. They did not make sure that the horse dummies pulled on wheels would not drown out the music in the hunting scene, nor did they intervene when one of the dozens of inflatable knights suspended from the flies began to swing jauntily from right to left and back again.

Tannhäuser, Act 3. Photo: Bettina Stöß

The minimalism of Holten’s Lohengrin from the very beginning was intended to serve a purpose; it emphasises all the more the spectacular nature of key scenes in the drama, including the appearance of the Swan Knight and his subsequent marriage to Elsa. This is a grim, dark production about war – not about Henry the Fowler’s expedition against the Hungarians, but about war as such, always the same, suggested by Steffen Aarfing’s costumes and sets, which refer equally to the fairy-tale Middle Ages and to the Dano-Prussian War of 1864 as well as earlier conflicts in northern Europe. It is also a production about wartime manipulation, a desperate search for a leader whom the oppressed people welcome with open arms: even if he comes from nowhere, even if he sets absurd conditions and treats everyone instrumentally, including Elsa of Brabant, who is waiting for a mysterious saviour. Instead of providing easy answers to the questions in this crime story with Gottfried in the background, Holten piles up even more mysteries. He leaves us uncertain as to whose victim Elsa’s brother was and whether he indeed was transformed into a swan. Lohengrin himself is a usurper swan, parading with wings attached to his back, a false archangel saviour, who in the Die Gralserzählung frantically turns the pages, as if until the last moment he could not decide with which version of the events to beguile his naive followers. The production features several memorable images: the “police-style” outline of a corpse, which from the very first scenes suggests that Gottfried will never return, the marital bed, which turns out to be a funeral catafalque, the sheet, unstained by traces of the wedding night, which in Act III will cover Telramund’s corpse. Again, no one will die in the finale, but shortly before the curtain comes down the chorus will stop Lohengrin, not letting him leave for an imaginary Monsalvat. We do not know what will happen next – except for a clear suggestion that the war machine has been operating in the same manner from times immemorial.

Lohengrin, Act 1. Photo: Bettina Stöß

Ironically, in musical terms the two productions stood in contrast with the stage concept. The moving Lohengrin, heavy-handed by the conductor Donald Runnicles, devoid of energy and with climaxes coming in the least expected moments in the score, was disappointing vocally as well. David Butt Philip, clearly indisposed that day, may have tackled the eponymous role too early. It is not enough to have a strong, handsome tenor with baritone hues to convey the multi-layered nature of the character and, above all, wisely pace yourself over the three treacherous acts of the opera. Jennifer Davis (Else), a singer with an otherwise pretty soprano, was flat almost throughout the entire evening; Ain Anger’s bass is too common and not very rich for the role of Henry; Iréne Theorin (Ortrud) too often had to make up for the deficiencies of her tired voice with overacting. The only bright point in the cast was Jordan Shanahan as Telramund – his full, healthy baritone was very much up to the demands of this truly tragic role: a man prepared to resort to any meanness to defend the time-honoured ancestral rules.

On the other hand the theatrically bland, at time grotesque Tannhäuser captivated the audience with the music – colourful, passionate and lively under the baton of a young Australian, Nicholas Carter. Stephen Gould may not be a singer who enchants with the power of his expression, but he has mastered the title role right down to the tiniest details and can still sing it thoughtfully with a technically-assured voice, just as the composer intended. Camilla Nylund, an artist with a luminous and excellently placed soprano, brilliantly sung the double role of Venus and Elisabeth. Markus Brück, an heir of the good old German school of baritone singing, proved to be one of the best Wolframs I had heard in recent years. Another singer deserving appreciation is Ante Jerkunica, whose warm, slightly “grainy” bass infused the role of Landgrave Hermann with plenty of tenderness and lyricism.

Lohengrin, Act 2. Photo: Markus Lieberenz

And yet it is Lohengrin that became embedded in my memory after this short, wind- and rain-lashed visit to Berlin. I came back to Poland to enjoy some sun. Three days later a war started: a war like the one in the vision presented by Holten, who in some prophetic inspiration revealed its less obvious mechanisms in the Berlin production. But even he may not have predicted that on the first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine Lohengrin would return to Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre after an absence of one hundred years. With a less ambiguous message than in Holten’s vision, I’m afraid. Over there they still trust knights who come from nowhere.

Translated by: Anna Kijak