Instead of a teaser – the CD is already available all over Europe: stay at home and go to the PWM’s online shop: https://pwm.com.pl/en/sklep/publikacja/drach-dramma-per-musica,aleksander-nowak,24030,ksiegarnia.htm. The LP on vinyl is ready for purchase here: https://pwm.com.pl/en/sklep/publikacja/drach-dramma-per-musica,aleksander-nowak,23931,ksiegarnia.htm.

***

The action of the second chapter of Szczepan Twardoch’s novel Drach is set in the years 1241, 1906, and 1918. As in the whole book, events take place on all the temporal levels at once. The chapter opens with the words: “A tree, a human, a roe deer, a stone. All the same.” A moment later, we hear the same words spoken in Silesian by old Pindur, who is a village philosopher and at the same time a village fool, derided by everyone around, but penetrating deep into the past with his instinct. For a brief moment we find ourselves in 1906 and sit on a fallen trunk with Pindur and eight-year-old Josef, called Zeflik by some. The libretto of the opera Drach, written by Twardoch himself, starts with similar words, but in Silesian: Czowiek, chop i baba, sŏrnik, hazŏk, kot a pies, a strōm, wszyjsko to samo (“A human, man and woman, roe deer, hare, cat and dog, and the tree, all the same”), sung this time by Drach, who is Pindur at the same time. He is a doubly omniscient narrator; not only a holy fool whom little Zeflik listened to, swinging his legs shod in shapely bootees; not only the dragon of Silesian legends, but the serpent of old, the gnostic Ouroboros, god of fertility and the dead, symbol of all things being one. He is everything: taste and smell, light and darkness, pure sunshine, tree and stone, a sacrificial offering and the barking of dogs, the earth damaged by tanks’ caterpillar tracks and furrowed by trenches, the soil that devours dead bodies and spits new life out of its entrails in the spring. He is a creature that sees, feels and hears everything, has a part in everything, is everyone, and is inferior to none.

When Aleksander Nowak told me of his intention to compose Drach and later sent me Twardoch’s complete libretto, I was afraid even to look at the text. True enough, I had already had the chance to see how Nowak takes advantage of his extraordinary sense of operatic potential inherent in contemporary literature, and of his equally uncommon ability to persuade writers that they should grapple with a form seemingly alien to their own sensitivity. The scripts of his successive operas have emerged as a result of painstaking negotiations and of equally laborious effort to educate the authors, who, though inexperienced in this field, under the composer’s guidance came up, to their own surprise, with clear and coherent narrations unfolding simultaneously on several levels and suited to the conventions of the music theatre. The libretto of Space Opera, written by Georgi Gospodinov, the Bulgarian master of ‘private apocalypse’, tells the story of the first manned flight to Mars from the perspective of an astronaut (married) couple, a stowaway fly that travels with them, the cynical flight manager, and a Chorus of Souls, made up of all the creatures ever sent by humans into the outer space. Its masterly construction in sixteen scenes (including prologue and epilogue) brings to mind associations with Britten’s Death in Venice. During his work on Ahat-ilī – Sister of Gods, based on Olga Tokarczuk’s Anna In in Tombs of the World, the composer managed to persuade the writer to shift the accents in her narration, confuse the protagonists’ tongues, and make the tale theatrical using all the means available. Both these projects undeniably proved a success. As for Drach, the idea was initiated in October 2018 by Filip Berkowicz, originator and curator of Auksodrone festival in Tychy, who wanted a ‘Silesian’ opera based on a Silesian topic and featuring a Silesian orchestra – AUKSO, under the baton of another Silesian, Marek Moś; an opera emerging as the joint work of a composer and a writer from that region. Still, I could hardly imagine how a vast and multi-layered saga of two families could possibly be condensed into a music work for three soloists and chamber orchestra with harpsichord, taking a bit more than an hour to perform.

Gleiwitz, Germaniaplatz, ca. 1915

Nowak warned his audience in advance that the unusual libretto replaces the traditional protagonists with personified emotions, whereas of the original plots and dramatic concepts only some vestigial traces have been preserved. As the composer had predicted, Szczepan Twardoch had rejected this proposal at first. Though they had Silesian roots in common, and shared memories of secondary school, artistically speaking they seemed to be poles apart. Twardoch later admitted that the idea appeared to him just as absurd as if he had been asked to dance in a ballet. He changed his mind, though, during a wintertime walk in the waterlogged fields near Pilchowice. He spotted roe deer, and when the beautiful creatures bolted away, he recalled that they also lived in Jakobswalde, had no names, and left their faeces in the fields. He recalled that he remembered it all, like Drach and Pindur, and so he decided he would start with the deer. He thus got down to writing, or rather – to distilling Drach into a myth about Silesia’s arché, the cyclic nature of time, and the inseparable link between humans and nature. The work took him less than a year. Nowak indefatigably supported his new librettist and patiently introduced him to the secrets of contemporary opera.

Nowak labelled his new piece with the old-fashioned term dramma per musica, thus referring to the origins of the operatic form and to the historical characteristics of late 16th / early 17th-century ‘music drama’, such as: declamatory recitatives resembling human speech; the use of the instrumental layer to emphasise the message and meaning of each situation; intense interplay of affections, supported by the introduction of selected rhetorical figures. The whole opens with a prologue, featuring a harpsichord in meantone temperament, which affords a highly expressive use of chromatic progressions. Already this extensive introduction comprises musical suggestions of the ‘eternal return’, from incessant repetitions of one and the same note to a rhetorical katabasis in the form of a descending melodic line. From the very beginning, the harpsichord produces disturbing and false-sounding ‘patterns’ centred around a few stable tonal centres.

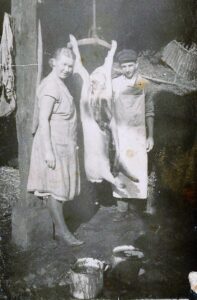

Pig slaughter near Pilchowice at the beginning of 1920th

The drama proper, told in three languages (Polish, Silesian, and German), takes on a curious, seductively beautiful musical form, meandering (or rather circularly reverting) from the Baroque beginnings to the extremes of modernism and back. This music curls in on itself like the immortal Drach – from expressive solo parts supported by a harmonically distorted accompaniment, to an interplay of tensions, brought to a halt and then relaxed in the ensemble sections, to truly Strauss-like tutti culminations. Nowak subdivided his work into three brief chapters, in which, as in Space Opera, the action takes place on several parallel planes. There is ‘realistic’ narration, in the form of He’s flashes of memories from his childhood and from the Great War; the story of his marriage to the girl who owned six acres in Żernica; as well as the episode of infidelity, which led him to murder and eventually madness. This interweaves with the ‘expressive’ narration, which represents pure emotions, both human and animal: the anxiety of a chased doe and her lost fawn; the mortal fear of a pig being slaughtered; the longing of a mother; the hunger of dogs; the pain of a neglected wife, and the lust of an unfaithful husband who does not have the courage to tell his spouse about “yonder German lass from Gliwice.” The vehicle of both these narrations is He’s baritone and She’s soprano, who stand for the male and all his women – the mother, the wife, and the lover. Both also symbolise the eternal ‘voice of all things’ – of the hare, the cat, the dog, the stone, and the tree. Of those creatures that live on Drach’s body and those that rot inside it after their death; also those that are born of the soil fertilised with the mortal remains. The human voice imperceptibly transforms into a pig’s squealing or a fawn’s grunting. All the same. Drach comments on all this from a distance, with the ambivalent voice of a countertenor, closing each ‘chapter’ of the drama with a prayer to himself, multiplied by a looper, which sounds now like a medieval lament, now – like a luminous Lutheran chorale.

Drach is not an opera about Silesia, just as the original novel is not about the writer’s Heimat. The operatic and the literary Drach is a soul that informs all living creatures. By paying homage to this soul, Nowak and Twardoch ennoble their Silesian homeland and elevate it into the sphere of myth, as the ultimate cause of all being and the fundamental component of reality; of a world governed by deterministic chance and by the ruthless laws of nature, in which everything is one, everything has its end, and everything returns. Thus all things are in Drach and are from Drach; Drach is dirt, coal, flesh, and sunshine.

The First Holy Communion of my uncle Henryk. Kattowitz, Königshütter Straße in the first half of 1940th

Time gets even denser in the last chapter of Twardoch’s novel, whose action takes place in 1915–1918, 1921, 1925, 1938, 1939, 1945, 1986, and 2014. This chapter ends with the sentence: “Frozen bare-calved corpses in the snowbound fields in front of the hospital; the January wind tears at their hospital gowns.” In the third chapter of Nowak’s opera, a soldier shoots at his own brother near Gliwice; a pack of dogs hunts down a doe between Pilchowice and Stanica, and Josef tightens the deadly grip around Caroline’s neck. Everything dies. “The light shineth not in darkness; and the darkness comprehendeth it.” And yet, catharsis will come, for it is only through death that the secret can be found out. Death lets one fathom the mystery of Silesia, get reconciled to its tragic history, refer to the collective wisdom and experience of the Silesian population. Curled in on himself, trampled by humans and deer, riddled with mineshafts, Drach watches from aside and prophesies: “Whoever is born shall die, and who dies must be born again.” This is the order of every world, even the smallest one.

Translated by: Tomasz Zymer