The artists who today can honestly be described as ambassadors of Polish culture in the world include several individuals whose careers I have followed from the very beginning. Agnieszka Budzinska-Bennett occupies a unique position among them: primarily because she has triumphantly followed the same path I began to tread tentatively in the early 1990s. The beginnings of a female medieval music ensemble which I co-led with Aldona Czechak for nearly a decade were as crazy as the whole era. I have said that it was beautiful but difficult. Experience gained at masterclasses in the West – where we were able to go with money scrimped and saved, borrowed or scrounged from institutions and foundations – were more often the subject of derision rather than genuine interest in Polish musical circles. I still find it hard to believe that we nevertheless notched up several important successes: first of all, abandon the „imitative” model of historically informed performance, common in Poland at the time, in favour of an engaged model requiring source research, work on manuscripts, comparative studies of vocal traditions and development of conscious improvisation skills. However, it so happened that I took up music criticism at more or less the same time. The conflict of interest grew. I gradually moved away from performance. Or maybe I simply lacked the determination, diligence, charisma and talent – all the qualities that have taken Agnieszka to the top and made her one of the leading specialists in this narrow and difficult field. By European, if not global standards.

I remember when she contacted me for the first time, while she was still a musicology student at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. She had already participated in several prestigious courses, including those with the British sopranos Evelyn Tubb and Emma Kirkby, for years associated with The Consort of Musicke. At the time I was involved in a research programme focused on the oeuvre of Hildegard von Bingen, initiated by Barbara Thornton and supported by Benjamin Bagby of the legendary ensemble Sequentia. I spent nearly two years shuttling between Poland, Belgium and Germany, gathering knowledge and experience, which we confronted every few months during intensive sessions at Barbara and Benjamin’s home in Cologne. Agnieszka – in love with the Middle Ages since childhood, engrossed in recordings by pioneers of period performance since high school, and confronting her life’s passions with the musicological knowledge at the university – inquired about everything in minute detail. Her passion, determination and a sense of self-worth as steadfast as it was justified made an electrifying impression on me. This exotic-looking, bright, energetic girl was a force of nature. I thought to myself that if she managed to take part in the courses taught by Sequentia’s co-founders, she would benefit a hundredfold more from them than I ever would. She managed to do that twice. And my intuition did not fail me.

Years later we started calling each other “sister”. This is because the beginnings of our foray into early music were surprisingly similar. From the beginning Agnieszka was fascinated by cooperation, teamwork. Although she conscientiously went through all levels of musical education in her hometown of Szczecin and received a diploma in piano at the end of her high school education, she never became friends with the three-legged black giant. She felt lonely at the keyboard: she was fascinated by the world of medieval dragons and heroes, courtly love and sophisticated poetry, over which she had been poring with dictionaries since childhood, absorbing the magic of foreign-sounding words and the melody of forgotten languages. She read Scandinavian sagas and Nibelungenlied, and then confronted them with Wagner’s Tetralogy. She devoured Beowulf as if it were the best crime novel. To this day she still has a weakness for fantasy literature and quirky television series, including Ragnarok, a Norwegian tale with more than one moral, the authors of which have brilliantly reinterpreted Norse myths to attract modern teenage viewers uncertain of their own identity. We recently shared our impressions of several episodes on Messenger, laughing uproariously and making sure no one was looking over our shoulders.

I spent years honing my reviews, essays and columns, while Agnieszka devoted herself wholeheartedly to musical archaeology and increasingly successful attempts to bring this world to life in performance practice. After the last semester of Poznań musicology, in 1997, she began her studies in Switzerland, at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, one of the most important centres of medieval music studies and the bastion of period performance. SCB students included Gustav Leonhardt and Jordi Savall; Sequentia, the fruit of Thornton and Bagby’s joint graduation concert, was also born within SCB’s walls; singing was taught there by the charismatic countertenor Richard Levitt, a member of the legendary Studio der frühen Musik, and a favourite teacher of Agnieszka, Andreas Scholl and… Sting, who used his advice when preparing an album of Dowland songs. It was there, in Heidrun Rosenzweig’s class, that Agnieszka mastered the basics of playing the medieval harp. It was there that in 1997 she founded the all-female ensemble Peregrina – or Wanderer – the name of which refers not only to a “pilgrimage” of musical ideas across medieval Europe, but also to the biographies of the ensemble’s members, who had come to Switzerland from the United States, United Kingdom and Finland in search of the musical Holy Grail.

Agnieszka Budzińska-Bennett. Photo: Laelia Milleri

Along the way, in passing, as it were, Agnieszka learned six languages, including Latin, indispensable in her work. She completed a programme in Scandinavian studies, and a post-graduate course in musicology at the University of Basel. While working as an assistant at the Microfilm Archive of the Institute of Musicology there, she met her future husband Lucas Bennett, and thus happily married the worlds of medieval and contemporary music (Lucas, a theorist and musicologist, specialises in twentieth- and twenty-first-century works; his father, the composer Gerald Bennett, a longtime collaborator of Pierre Boulez, whom he helped found the famous IRCAM in Paris, is one of the world’s foremost authorities on computer and electroacoustic music). Agnieszka sealed her impressive education with an honours degree in vocal ensemble conducting from the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis and a doctorate, defended in Poznań, on subtilitas, that is what can and cannot be heard in motets of the ars antiqua period. That was in 2010.

Peregrina already had two albums to its credit at the time: Mel et lac with twelfth-century Marian hymns and Filia praeclara with chants of the Poor Clares from Stary Sącz, for which I nominated Agnieszka for the first time for the Polityka weekly’s Passport Award. The nomination went unnoticed. The following year I mustered a small lobby, thanks to which Agnieszka made it to the top three “for her passion as a researcher who prepares concert and recording programmes through painstaking musicological, philological and historical work. For the excellent Crux album of Parisian Easter music from the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century”. The Passport eluded her again. In 2012, with a persistence worthy of Cato the Elder, I urged the award jury members to open their ears to the artist’s new achievements, submitting her nomination “for another excellent album, Veiled Desires, an anthology that recounts the life, spirituality and sexuality of medieval nuns by means of music of that era. For her ability to embed artistic activity in a broader social and historical discourse. For the reliability of her source research, which is an essential part of the work of musicians performing early music”. Made it to the final again, passport denied again. Agnieszka hugged me backstage and asked me politely but firmly not to nominate her again.

I complied. However, I missed no opportunity to preach about Saint Agnieszka of Basel and her solid craftsmanship, which needs no passports. I appreciated the fact that in 2016 she was entrusted with the artistic supervision of a huge project of recording all the Melodies for the Polish Psalter by Mikołaj Gomółka with the Polish Radio Choir, but I still thought there was not enough response in Poland to what was closest to the hearts of both of us: medieval music. Music that is free of splendour, only seemingly easy, but in fact requiring maximum precision and concentration from the performers – in some ways similar to the Japanese Zen gardens, which encompass the entire universe, where gravel is raked into waves for hours, and a few stones are placed within a tiny space in such a way that it is impossible to take them all in at once.

Not everyone likes monochromatic landscapes of sand, moss and rock chips. Nor does everyone feel safe in them. So Agnieszka decided to rake, arrange and water her beloved music all the more calmly to give the listeners space and help them extract as much meaning from it as possible. She herself once recalled a mesmerising performance by Benjamin Bagby, who improvised an extensive passage from the Old English epic poem Beowulf, accompanying himself on a six-stringed lyre. His monologue went on for more than an hour, only some intelligible words could be extracted from the text, and yet, according to Agnieszka, everyone guessed at which point the monster “moved the third claw of its left hind paw”.

Agnieszka with Ensemble Dragma. Photo: Alejandro Lozano

With time similar things began to happen at her concerts. It is as if each one begins, as in Beowulf, with the famous cry of “Hwaet!”, which is usually translated as “Listen!”. In fact, it literally means “wait” and so the listeners obediently wait. Until a meaning emerges, until an image is outlined before their eyes, until hundreds of sounds, inconspicuous as couch grass flowers, form a symbolic pattern. The more inquisitive among the listeners will later start looking for contexts. The less inquisitive – or those simply tired of the chaos of the modern world – will be content with the sheer beauty of the composition.

Agnieszka is fully aware that it is impossible to impose on the audience one correct model of listening. Medievalist-musicians sometimes spend months preparing a short piece. They have to decipher it on several levels: read and understand the text, accurately interpret the notation, place the composition in a social, historical or liturgical context, combine it with the appropriate instrumentation if necessary. If doubts arise, they have to resolve them in the archives or ask colleagues for help. Once everything is ready, they have to check, if it can be played or sung at all. If not, they have to go back to the beginning and start all over again. They go to a lot of trouble and the listener may still turn a deaf ear to such an inconspicuous trifle. It thus takes a skill to arrange a programme, which in the case of medieval music is much more susceptible to the vagaries of acoustics, interior architecture and the general nature of the space.

This is why when I set off to attend the Swiss concerts under the “Kras 52” project, carried out by Agnieszka in cooperation with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, I asked the organisers to let me listen to the same programme twice: in the late-Gothic Calvinist church in Biel in the Canton of Bern and the following day in the fifteenth-century Haus zum Hohen Dolder in Basel, the former seat of a medieval society from the monastery village of St. Alban, whose duties included overseeing local vineyards, settling border disputes and fire protection of the monastery’s estates.

A manuscript marked by the mysterious signature Kras 52 was once kept in Warsaw’s Krasiński Library in Okólnik Street. It ended up there in 1857, as part of the legacy of Konstanty Swidziński, a bibliophile, art collector and patron who before his death had amassed a collection larger than that of the Ossoliński Library at the time. More than half of the collection – including the building – went up in smoke in October 1944, in a fire set by the occupiers after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising. The manuscript was miraculously found three years after the war in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, where Karol Estreicher recognised it by its light-coloured leather binding and ornate inscription “Manuscript from the fifteenth century”. In addition to the sermons of Jacobus de Voragine, Gesta Romanorum collection and a treatise on the expulsion of demons, it contains more than forty works in black mensural notation with music by composers of the late ars nova period and early Franco-Flemish polyphony, as well as seven of the nine surviving compositions by Mikołaj of Radom, and other musical relics associated with Kraków and the court of Władysław Jagiełło.

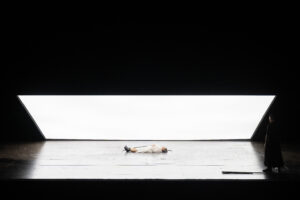

Photo: Alejandro Lozano

The first part of the project, entitled Regina Gloriosa, is based on a Marian repertoire – a fascinating testimony to the interpenetration of Italian, Avignonian and local influences, as well as the earliest Polish, still tentative experiments with Western polyphony. Agnieszka, this time with Ensemble Dragma – made up of her regular collaborators – presented one of the most subtle and sophisticated programmes of recent years. Divided into four parts (Marian Mass, music for Christmas and Epiphany, music for the Presentation of the Lord, and Marian prayers separated by the Magnificat), and performed with only five musicians, it not only revealed the light texture of these works, translucent like parchment, but also, with its thoughtful arrangement and a few wisely chosen additions from other sources, effectively sustained the attention of the entire audience. Without flamboyance, but with the tried-and-tested method of delicate contrasts – Agnieszka’s sensual soprano with Tessa Roos’ angelic, focused voice, intriguing dialogues between the harp and Marc Lewon’s lute, conversations carried out in such an expressive whisper of the instruments that whenever Jane Achtman and Elizabeth Rumsey’s vielles and Lewon’s gittern joined in, the medieval ensemble gave the impression of total completeness.

The same music – which rose like a pillar of light towards the vault of the Calvinist church – heard in the tiny hall of the Haus zum Hohen Dolder with its squeaky boards spoke directly to the listeners, sometimes from a distance of less than a metre. And once again I was able to experience the quality of these performances, just as I experience the mastery of opera singing in modest five-hundred-seat theatre. In such conditions musicians stand before the audience exposed as they were at birth. Ecce homo. Ecce mulier. Any deficiency in the technique would have resounded in this chamber with the power of the trumpets of Jericho.

When it was all over, when – like in the good old days – we cleaned the room together and washed the dishes, Agnieszka’s family invited me to dinner at a restaurant the name of which I will not reveal. Look for yourself where to eat the real braised brawn and ossobuco in Basel. Because what I also have in common with Agnieszka, her husband Lucas, her beloved father-in-law Gerald and his partner Pam is that we like to eat well and sip good wine to go with the feast. We also love to cook, finding in this a delight similar to browsing through ancient archives. Next time we will make ourselves some Spanish salsify with red lentils or spicy chicken with pumpkin. Perhaps I will be able to rival Agnieszka in this particular art.

Translated by: Anna Kijak