’Down all the roads, gleaming with the puddles of spring waters, leading from all the furthest corners of the world to that promised land, down all the footpaths, meandering across the greening fields and blossoming orchards, across forests filled with the scents of young birchtrees and of spring, through obscure villages and impenetrable marshes – crowds of people flocked, hundreds of carts creaked, thousands of train carriages flew like lightnings, thousands of sighs rose and thousands of flaming gazes fell into the darkness, seeking with craving and fever the contours of that promised land.’

That is one of the last paragraphs of Władysław Reymont’s famous novel, published as installments by the Warsaw daily ’Kurier Codzienny’ and later in book form by Gebethner and Wolff’s Publishing House in 1899. The fortunes of Polish, Jewish, German and Russian factory-owners kept growing, while the several hundred thousand city suffered: ignored by the Tsarist authorities, tragically short of investment funding, socially undeveloped, deprived of modern infrastructure. There was a lack of a sewage system. There was a lack of waterworks. There was no lack of paupers and illiterates. 'For the sake of that polypus, villages were being deserted, forests died, the soil was losing its riches, rivers dried up, people were being born, while it sucked everything in (…) and in return gave useless millions to a handful, and hunger and strife to the masses.’

The German and Jewish elites met their cultural needs elsewhere: either in nearby Warsaw or distant Berlin. In November 1918, when Łódź became part of the reborn Polish state as the second largest city in the country, Poles constituted just a little over a half of its population. Once again, it lacked support from outside: the mission of the metropoly’s development was left solely in the hands of the local authorities. Teachers began to come to 'the city of illiterates’ – as Reymont’s promised land was sometimes called – mainly from the former Austrian Partition. Together with the representatives of free professions, they made up the nucleus of the Łódź intelligentsia. They began their mission at grass-root level: by introducing compulsory school education and organising a modern school network. In 1922, the first public children’s library was founded. In September 1927, the premiere of the film titled Łódź – the City of Labour, directed by Edward Puchalski, a pioneer of Polish cinematography, took place at the 'Luna’ cinema in former Przejazdowa Street. Three years later, in the City Hall in Plac Wolności (Freedom Square), the exposition at the City History and Art Museum was opened, one of the first museums of modern art in Europe, which in 1929 began to collect the works of the so-called grupa a.r., a leftist avantgarde group of artists gathered around Władysław Strzemiński, his wife Katarzyna Kobro and Henryk Stażewski. The Radio Broadcasting Station (Radiowa Stacja Przekaźnikowa) began transmitting its programme in middle waves in February 1930.

Karl Wilhelm Scheibler’s factory complex in Łódź, late 19th century litograph.

Yet artistic studies and experiences had to be sought in other centres. The City Theatre (Teatr Miejski), taken over from the former authorities, the Popular Theatre (Teatr Popularny) founded in 1923 and the Polish Theatre (Teatr Polski), opened thirteen years later but lacking its own premises, all struggled with constant financial stringencies which were also translated into low artistic quality of productions. Despite pompous plans to open a Polytechnic as well as commercial, textile and medical schools of higher education, in pre-war Łódź there was only a private College of Social and Economic Studies, a Teacher Training College and a local department of the Free Polish University, the only school of higher education whose graduates could seek to obtain a Master’s degree, but not in all fields of study.

It was impossible to live without music, though: even in the intestines of an industrial monster, which 'ground and chewed people and things in its mighty jaws’. Moniuszko’s Flis and Verbum Nobile had been put up in Łódź already in the days of the Tsar, at the initiative of the 'Lutnia’ Singing Society. More or less at that time, the Construction of the Polish Theatre Joint-Stock Company was founded, which sold shares for the price of 25 rubles. The theatre failed to be built, but in 1915, the Łódź Symphony Orchestra came into being, organised by Tadeusz Mazurkiewicz. The first concert took place in the wooden Grand Theatre in Konstantynowska Street, and the original cast included Paweł Klecki and Aleksander Tansman. Three years later, in cooperation with the local Chopin Society, the Orchestra musicians organised an Opera Section. Most of the shows they put up were conducted by Teodor Ryder, a graduate of the Darmstadt conservatory, conductor at the Lyon Opera and at the Warsaw Philharmonic. In his days, the citizens of Łódź had the opportunity, among others, to watch and listen to Moniuszko’s Halka and Verdi’s Il trovatore. Critics reacted to those performances with mixed feelings, despite the participation of such Warsaw stars as Ignacy Dygas and Stanisław Gruszczyński. The level of the makeshift ventures, in which a medley of musicians took part to support the Łódź Orchestra, was not exactly breathtaking, yet they were hugely popular with the audiences.

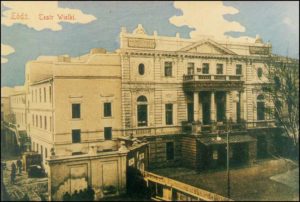

The old Grand Theatre. Postcard from the beginning of 20th century.

Up to a moment. The Grand Theatre, built in 1901 to the design of the Łódź architect Adolf Zeligson, with its wonderful neo-Renaissance façade and 1200 seats in the audience, was completely burnt down on 20th October 1920. Six years later, Aleksy Rżewski – the first President of the city in the inter-war period – set up the Łódź Opera Society. Another inkling of hope for a regular stage dawned. The aforementioned Teodor Ryder became the artistic director and inaugurated the society’s activity with a show of Halka at the City Theatre (7th March 1926), performed by local ensembles and soloists from the Vilnius opera, dismantled a year earlier, and conducted by Daniel Kleidt. The initiative soon withered away, though Łódź citizens would still for a long time recall the later performance of Madama Butterfly starring Teiko Kiwa, presumable Japanese, whose name was really Laetitia Klingen and who was the daughter of a Dutch chemist and his half-blood Japanese wife. The singer was immensely popular in the role of Cio-Cio-san, whom she played on the stage over seven hundred times.

Attempts to instal the opera on the stage of the just renovated City Theatre in Cegielniana Street, undertaken by Ryder in the 1930’s, ended in a fiasco. The proudly announced premieres of The Haunted Manor, Tosca and La Traviata never took place. Then the war broke out. The city had to wait until 1954 for its first proper Opera House. The institution, officially founded on the 1st of July by the act of the local National Council, was first and foremost a fruit of passion and involvement of Władysław Raczkowski, pianist, organist, choir master and conductor, who organised the first rehearsal of the ensemble in his own flat. Sabina Nowicka, former deputy director at the Polish Army Theatre (Teatr Wojska Polskiego) in the reign of Leon Schiller, and then of the newly-founded Stefan Jaracz Theatre (Teatr im. Stefana Jaracza), became the managing director of the Opera. Mieczysław Drobner, musicologist, composer and pedagogue, lecturer at the Higher State School of Music in Łódź, became the Opera’s musical director. The activities were inaugurated on the 18th of October 1954 with The Haunted Manor conducted by Raczkowski and directed by Jerzy Merunowicz, the latter a member of the original troupe at the New Theatre (Teatr Nowy) – the stage that had taken turns with the Stefan Jaracz Theatre to host the Opera’s productions. There were young singers in the newly created ensemble who with the passage of successive seasons contributed to the excellent renown of the Łódź Opera – such as Zofia Rudnicka, one of the most beautiful and technically perfect sopranos on the post-war Polish stages, and Weronika Kuźmińska, memorable Hanna in The Haunted Manor mentioned above, equally wonderful Tatyana in Eugene Onegin in 1956, and Mařenka in Smetana’s The Bartered Bride staged two years later.

Lidia Skowron (Halka) and Jerzy Jadczak (Janusz). The opening night of Halka at the Łódź Grand Theatre, 1967.

In 1966, the Opera – renamed The Grand Theater in Łódź – began moving to its new premises in Plac Dąbrowskiego (Dąbrowski Square). The construction of the building, designed by Józef and Witold Korski and Roman Szymborski as a dramatic theatre, lasted with intervals for eighteen years. The National Theatre, for that was originally to be its status, was destined to become an opera in 1954, when the Act of National Council, founding the Łódź Opera was passed. The project evolved, but its authors and those who were implementing it from the very beginning intended to organise the vast area of the square in line with the principles of socialist realism, situating in its northern frontage one of the biggest and most representative objects of the new architecture in the country. The form of the building was to be heavy and at the same time harmonious: huge pillars run along two storeys of the edifice, set at equal intervals, bringing to mind associations with symmetry in the ancient meaning of the term, synonymous with the then conceptions of beauty and moderation. The theater’s interior, with its audience originally designed for almost 1300 seats, was a prominent example of a dialogue – and sometimes of an architectural argument – with the traditional model of an opera hall, identified by the distinctive horseshoe-shaped arrangement of galleries and balconies piling up around. The audience in a way 'grew into’ the stage, penetrated inside the proscenium arch; the sumptuous composition of the plafond, made up of characteristic, suspended 'kites’, was to replace the interplay of light from a monstrous crystal chandelier, customarily fixed in the centre of the ceiling. Łódź saw its theatre as a huge one – second in size after the Grand Theatre in Warsaw and one of the biggest in Europe.

The managing director Stanisław Piotrowski, and his artistic counterpart Zygmunt Latoszewski – musicologist and an experienced opera conductor, since 1965 professor at the Warsaw Higher State School of Music – had planned four premieres for the opening, staged day after day. Thus, the first was Halka, on the 19th of January 1967, the twenty second anniversary of the liberation of the city. On the following day, Borodin’s Prince Igor was presented, then The Haunted Manor and, finally, Carmen by Bizet. Soon special trains were set up to run between Warsaw and Łódź, bringing opera lovers unsatiated by the impressions they had carried out from the capital’s Teatr Wielki – the opera house heaved up from the ruins, expanded and put into operation almost a year and a half earlier.

Łódź was awakening once again, just as in Reymont’s novel. The opera promise had finally been fulfilled.

Translated by: Katarzyna Kretkowska