Frenzy, insanity or mental illness? The autumn season at the Welsh National Opera, arranged under the heading of ‘Madness’, has obliged us to reflect upon several forms of lunacy. Three compositions superficially divided by everything: a masterpiece of Baroque opera, the swansong of a master of classic bel canto and a musical defying all attempts at categorization. Three extremely different characters: a knight possessed by jealousy; a girl caught up in religious and political intrigue, who loses her senses at the thought of her fiancé’s supposed unfaithfulness; and a barber motivated by a psychopathic lust for revenge. But nonetheless, the idea – from a musical standpoint quite awkward – to combine Händel’s Orlando, Bellini’s I Puritani and Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd turned out to be considerably more coherent than in the case of last year’s series ‘Liberty or Death’ series, in which Carmen played the quite far-fetched role of a unifying force for two rarely-performed Rossini operas.

This time, we decided to catch the WNO in Oxford: among other reasons, in order to ‘check out’ this ensemble in the difficult acoustic conditions of the New Theatre, about which I wrote in one of the October articles on this page. I was consumed with curiosity about how Annilese Miskimmon, the creator of an extraordinarily intelligent and precise staging of Jenůfa for the Scottish Opera, would handle the dramaturgically weak I Puritani. I was a little (well, even very!) worried about Orlando in the staging of Harry Fehr, who shifted the action of this dramma per musica into the realities of an English hospital and the time just after the outbreak of World War II. I was looking forward to Sondheim’s ‘black operetta’ – a musical at moments closer to Ravel, Prokofiev and Britten than the insipid music of big-budget Broadway productions. Frankly, I couldn’t wait for this season, because production of Baroque operas in Poland is the exclusive domain of enthusiasts associated with the historical performance movement; Bellini is avoided by our theatre directors like fire; and if anyone aside from specialists and the more refined lovers of the musical œuvre has heard of Sondheim, then it was only in the context of the film version of Sweeney directed by Tim Burton.

New Theatre Oxford turned out to be even more cramped and poorly adapted to presentations of music theatre works than we had originally thought. The hall, more capacious than Warsaw’s Grand Theatre–National Opera, literally merges into the stage; the audience is crowded into densely-packed rows, and there is no orchestra pit. The instrumentalists occupy the space left behind by seats removed from the front portion of the ground floor, separated from the audience by a low, temporary barrier. No wonder that in the first act of I Puritani, the soloists and the orchestra were occupied, above all, with ‘catching’ the sound proportions. However, this went more smoothly than expected, for which enormous credit goes to Carlo Rizzi, who from the beginning took care not only of the work’s big picture, but also of its meticulously-executed details, chief among them a beautiful, typically bel canto-style rubato, shaped in ideal accord with the disposition of the individual singers. All the more importantly that Barry Banks, expected in the role of Arturo, was substituted at the last minute by the young Italian Alessandro Luciano, a singer gifted with a nice voice and decent technique, but clearly inexperienced and insecure in the murderously high notes that Bellini did not spare the lead tenor in this opera. Linda Richardson (Elvira), playing opposite him, came out decidedly better, though after listening to fragments of ‘Vien diletto, è in ciel la luna’ in the rendition of the phenomenal Rosa Feola from the WNO trailer, I deeply regret having happened upon the other cast for this role. Richardson’s interpretation – though correct and completely period-appropriate – was lacking in girlish lightness and the charming freedom of coloratura figures showcased by her predecessor. David Kempster took a long time to warm up in the role of Sir Riccardo, one basically inappropriate for this baritone, who reveals the fullness of his artistic values in the later Puccini and verismo repertoire. I am all the more pleased to report upon the superb debut of Wojtek Gierlach in the role of the good-hearted Sir Giorgio, singing with fluid phrasing and a soft, round color (in ‘Suoni la tromba’, he made a splendid duo with Kempster, who felt much more at home in this proto-Verdian duet). The minor deficiencies in the solo parts, however, faded into oblivion before the brilliant musical vision of Ricci, who strongly emphasized the dialogical character of I Puritani, ensuring that the singers, orchestra and chorus (outstanding as usual) built a transparent narrative and did not try to drown each other out.

I Puritani. Wojtek Gierlach (Sir Giorgio), Rosa Feola (Elvira), Sian Meinir (Enrichetta). Photo: Bill Cooper.

Miskimmon based her staging on a surprising idea: she decided to take literally Elvira’s complaint that three months of separation from her beloved are like ‘tre secoli di sospiri e di tormenti’. Similarly to Jenůfa, she shifted the action to the realities of Northern Ireland, judging from the costumes (stage design by Leslie Travers) in the 1970s, the time of Na Trioblóidí, i.e. the infamous political and ethnic Troubles. The wedding preparations play out in parallel with the organization of the Orange Order demonstration in July – an annual Protestant parade in honour of William III’s victory over the Jacobites. A sudden and stormy shift of the narrative to 1649 is the first sign of the heroine’s psychological breakdown – the two time planes, each one with every ‘i’ dotted and every ‘t’ crossed as always with Miskimmon, continually merge into each other. The contemporary Elvira follows her 17th-century alter ego step by step. And here the first dissonance appears: the silent twin, after a suggestive first entrance, wanders aimlessly about the stage; instead of filling in the narrative, she just disturbs it. This is nothing, however, in comparison with the solution adopted in the finale: after the breathtaking scene in which the messenger arrives with news of the amnesty (the black-and-white character enters the Orange hall like something out of a dream), Miskimmon changes the ending and gives poor Arturo over to death at the hands of the Unionists. As a consequence, Arturo disappears from the final ensemble number. I would not have suspected that such a musical stage director would permit herself to do such obvious violence to Bellini’s score – especially that her provocative vision, despite the aforementioned reservations, does actually hold together for most of the opera.

The next day, my disappointment unexpectedly turned into admiration. Harry Fehr had done the impossible: he had set the action of the ‘magical’ Orlando in a very concrete space and time, with all of the fantastic elements coming from the sickened mind of the protagonist, a heroic airman suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. The director does not modernize the narrative by force – everything takes place in the meticulously-reproduced scenery of a hospital from the 1930s (stage design by Yannis Thavoris, playing wonderfully with the Art Deco-style interior of the New Theatre). There is the mentally-ill Orlando and the physically-crippled Medoro. There are two female rivals: the aristocratic Angelica and the modest, straight-laced nurse Dorinda. The strings are pulled by the demonic Zoroastro – the medical director, a peculiar cross between Mesmer and Freud, an omnipotent doctor who sets himself the goal of healing the protagonist and sending him off to battle with the enemy of the homeland. The entire concept could have fallen flat if Fehr had not worked out every detail and paced every gesture with the individual phrases of the libretto. The static narrative suddenly picked up its pace; the improbable twists in the plot gained a psychological justification. A few scenes and theatrical ideas will remain in my long-term memory: the scene where Orlando is ‘conditioned’ with the aid of slides from the Duke and Duchess of Windsor’s visit to Hitler in Berchtesgaden; Angelica’s emerald-green gloves in the aria ‘Verdi piante’; the daring idea of supposedly destroying Dorinda’s house as part of Orlando’s shock therapy. If we add to this the phenomenal acting of all of the singers (as well as choristers in non-speaking roles), we obtain a stage vision, the coherence of which would be appreciated from beyond the grave even by the director of (at that time) His Majesty’s Theatre in Haymarket, where Orlando had its world première.

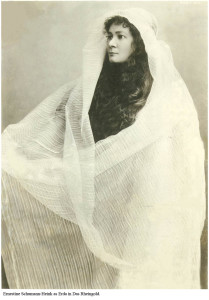

Orlando. Lawrence Zazzo. Photo: Bill Cooper.

I also will spare no compliments to the musicians. The WNO orchestra, prepared by Rinaldo Alessandrini, played in Oxford under the baton of Andrew Griffith. With a knowledge of style that not a few continental Baroque ensembles could envy it (despite the violette marine originally used in Act III being replaced by ‘ordinary’ violas). I have already written about my doubts concerning the casting of Orlando and Medoro previously – on the occasion of the Polish première of Händel’s masterpiece. My doubts have remained, especially in reference to Robin Blaze, who was not able to breathe any life into the part of Medoro, scored for female alto. Lawrence Zazzo in the role of Orlando, however, made up for all of his vocal deficiencies with wonderful scenic gesture, creating a character of flesh and blood – at moments grotesque, at moments tragic, convincing in every respect. Rebecca Evans turned out to be the brightest star of the evening: a lofty, somewhat distant Angelica, but at key moments moving one to tears – above all, by virtue of flawless technique and feel for style. Nor can one remain indifferent to the vocal art of Fflur Wyn (Dorinda), one of the most versatile light sopranos among the soloists at WNO.

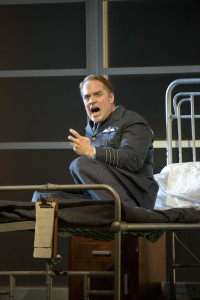

It is no wonder, then, that after such experiences, I received the staging of Sweeney Todd without any great emotion. In this case, James Brining’s shifting of the action to the 1970s found no justification. The action moved quickly, images came and went as if in a kaleidoscope, but the drama of the mad barber – which is, after all, very firmly set in the realities of Victorian London – did lose credibility. Perhaps also on account of David Arnsperger, the German artist in the title role who was making his debut at the WNO, and who – to make things worse – sang in correct, but completely ‘transparent’, impersonal English. The strongest point in the cast turned out to be Scottish soprano Janis Kelly, who was sufficiently good as an actress, as well as vocally competent, to eclipse Sweeney in the role of Mrs. Lovett. There is also no way to overestimate the artistry of Paul Charles Clarke, who in an awesomely cavalier manner took on the role of Pirelli and parodied his own – otherwise splendid – technique of a lyric tenor accustomed to the Italian repertoire. I would prefer to assess the craftsmanship of the remaining soloists, especially Soraya Mari (Johanna) and Jamie Muscato (Anthony) in other conditions, without microport amplification of the singers. I shall again praise the superb work of the chorus and sensitive playing of the orchestra under the baton of James Holmes, but I cannot get rid of certain objections: since the WNO is raising Sondheim’s œuvre to the rank of a full contemporary opera (and not without reason), why is it hesitant to perform it ‘as God commanded’ – without amplification, on the natural forces of perfectly-trained vocalists?

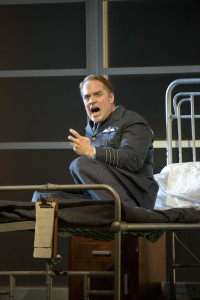

Sweeney Todd. David Arnsperger and Janis Kelly (Mrs. Lovett) and the chorus. Photo: Johan Persson.

But now let us bring the matter back down to earth. We got three shows, sometimes controversial in terms of staging, but despite slight reservations superb from a musical standpoint. We happened upon them on tour, in immeasurably difficult acoustic conditions, in the final phases of their tour, when just plain human exhaustion could have been coming into play. I would wish for such premières at Polish opera houses. I would also wish everyone an equally friendly and objective audience.

(Translated by Cara Thornton)