It took me eight years to come full circle and return to the beginnings to my freelancing career. In 2014, instead of celebrating the 160th anniversary of my favourite composer at home by the loudspeakers, I decided to go to a performance of The Cunning Little Vixen in a production that originated in Prague and was brought to Brno for the Janáček Brno festival – the motto of which was “Happy Birthday Leoš!”. After more than two decades on the editorial board of Ruch Muzyczny I made my debut as a freelancer with a review of Ondřej Havelka’s production. Janáček’s oeuvre has always been at the top of my priorities as a reviewer. As it happened, however, I made it to the Brno biennial for the second time only now: partly because I was always at a loss as to what to choose from the festival’s rich offerings. I nearly gave up again, because this year the organisers exceeded themselves: the programme of the nineteen-day event included no fewer than thirty-six musical events, among them five opera performances, headed by the hosts’ production of From the House of the Dead combined with the Glagolitic Mass, directed by Jiří Heřman and conducted by Jakub Hrůša, the newly appointed successor to Antonio Pappano at London’s Royal Opera House; as well as non-operatic performances of the Orchestra of Welsh National Opera, conducted by its boss Tomáš Hanus, and of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande with Tomáš Netopil. I decided to content myself with the last four days of the festival, not wanting to miss a rare opportunity to hear Erwin Schulhoff’s only opera Plameny in its entirety. For the next two years I will wonder how to see the most of the 2024 biennial, which will last over three weeks.

Janáček Brno is a fairly new venture, launched in 2008 with an overview of all stage works of its patron. With time music by other composers was added to Janáček’s oeuvre, making it possible to show his legacy in a broader context of the period. However, the main programme axis is still opera of the modernist era – which is what adds uniqueness to the event, appreciated by, for example, the jury of the International Opera Awards, who in 2018 presented Janáček Brno with an award for the best festival. I have written many times about how the Czechs love their national repertoire and know how to popularise it all over the world. When I was in Brno I saw once again that they also know how to appreciate the mastery of foreign performers, but – unlike my compatriots – do not feel that their own music requires persistent promotion by great stars from the West.

Věc Makropulos. Nicky Spence (Gregor) and Ángeles Blancas Gulín (Emilia Marty). Photo: Marek Olbrzymek

This is hardly surprising given that Czech conductors – well-versed in the idiom of Central and Eastern European music – head some of the best orchestras in the world. I had an opportunity to admire Tomáš Hanus shortly before the outbreak of the pandemic: in a brilliant interpretation of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride at the Bayerische Staatsoper, and soon after that at the helm of WNO in a stylish and disciplined approach to Prokofiev’s War and Peace. On the day of my arrival in Brno, which happened to coincide with the Czech Struggle for Freedom and Democracy Day, Hanus led the Welsh orchestra in a programme consisting of Britten’s Four Sea Interludes, Dvořák’s Biblical Songs, Wagner’s Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde and Janáček’s Sinfonietta, which was highly appropriate in the circumstances. I had the impression that Hanus felt the least “at home” in Wagner’s music – played too smoothly, without an inner pulse and appropriate gradation of tension. On the other hand he was able to beautifully highlight the exuberant contrasts and shimmering nature of the textures in Britten’s Interludes and at the same time surprisingly emphatically stress the composer’s Mussorgsky inspirations (for example, in the swaying Allegro spiritoso). He provided a wonderful example of collaboration with the singer in Dvořák’s songs – Adam Plachetka’s velvety bass-baritone is often lost in the sumptuous acoustics of grand opera houses; in Hanus’ subtle interpretation the soloist impressed not only with the beauty of his voice and soft phrasing, but also with wisely delivered text, taken from the 16th-century Kralice Bible. But all this was nothing in comparison with the thrilling performance of the Sinfonietta, in which the fanfare – as Janáček would have it – was played by thirteen musicians of the Czech Armed Forces’ brass band. Unlike most symphony orchestra players, they did it without a single slip-up, which clearly suggests that Janáček knew what he was doing. The concert received a tumultuous and fully deserved standing ovation, which may have contributed to WNO’s even greater success in the performance of Věc Makropulos the following day.

To this day I shudder at the memory of the only staging of this masterpiece in Poland, presented exactly ten years ago at Teatr Wielki-Polish National Opera, when the spectators – lured by a misleading promise of a science-fiction comedy, accustomed to the image of a cheerful Czech over a pint of beer, and unfamiliar with both Janáček’s oeuvre and Karel Čapek’s bitter dystopia – began to leave the auditorium in droves already halfway through the performance. What must have also contributed to this was the inept playing of the orchestra under Gerd Schaller, who not only failed to control the various instrumental groups, but also to explain to the musicians what the score was about. Hanus didn’t have the slightest problem with this, probably also because he had been poring over the score for months together with Jonáš Hájek and Annette Thein, preparing a new edition for the Prague branch of the Bärenreiter publishing house. In addition, in their interpretation of Janáček’s operas British musicians equal and sometimes even surpass Czech performers. Among the members of the international cast of WNO’s Věc Makropulos the most pleasant surprise came from the Spanish soprano Ángeles Blancas Gulín in the role of Emilia Marty – a singer endowed with a small but very charming and exceedingly expressive voice, appropriately “old-fashioned” for this difficult part, and supported by excellent acting and a great feel for the character. When it comes to the rest of the cast, the most noteworthy performances came from Nicky Spence as Gregor, David Stout as Baron Prus and the ever-reliable Mark Le Brocq as Vítek, whose monologue explaining the intricacies of the libretto – during the interval between the first and second acts – won far more approval from the Czech audience than from the blasé spectators at the Cardiff premiere. Yet who knows, perhaps my most vivid memory of the production – in a pared-down, but very stylish staging by Olivia Fuchs (director), Nicola Turner (set and costume designer), Robbie Butler (lighting designer) and Sam Sharpless (video projections) – will be Alan Oke’s brilliant performance in the episodic role of Count Hauk-Šendorf. In any case, it has to be said that the creative team hit the nail on the head when it came to Čapek’s and Janáček’s message – this is one of the masterpieces of the modernist grotesque, which in the finale should force guffaws back down our throats and transform them into helpless sobs. The creators of the Welsh production fully succeeded in this.

Plameny. Tone Kummervold (La Morte) and Denys Pivnitskyi (Don Juan). Photo: Marek Olbrzymek

Not quite so in the case of the creative team of the eagerly awaited Flammen, brought from the National Theatre in Prague and presented in its original Czech version as Plameny. Schulhoff’s only opera was unlucky, as was its composer: after the failure of the Brno premiere, nothing came out of Erich Kleiber’s plans for a Berlin staging, due to the Nazi campaign against modern art. Schulhoff, cursed as a representative of Entartete Kunst, and hated as a Jew and a communist, after the Nazis seized Czechoslovakia he applied for Soviet citizenship, which did not protect him from deportation to the Bavarian fortress of Wülzburg, where he died of tuberculosis in 1942. He came up with the idea for an opera loosely based on the myth of Don Juan in 1923 and discussed his vision with Max Brod, a friend and biographer of Kafka, and translator of Janáček’s librettos into German. Brod advised him to collaborate with the Czech scriptwriter Karl Josef Beneš, who together with Schulhoff created an oneiric, surreal tale of a seducer in love with Death – the only woman he is unable to seduce and who ultimately seals his fate. The dissolute Don Juan will not end up in hell: the punishment for his transgressions will be the curse of eternal life, with no hope of fulfilment.

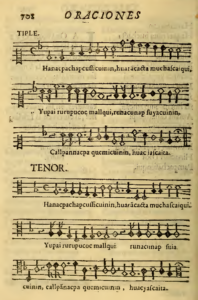

Schulhoff got down to work on the score in 1929 and slugged away at it for three years. The premiere in January 1932, at the Divadlo na Veveří, the former seat of the National Theatre in Brno, was a complete fiasco. The audience rejected not only the unique structure of the work – which combined elements of opera, pantomime and symphonic poem – but also its exuberant eclecticism, vacillating between impressionism, brutal expressionism and relatively orderly neoclassicism. Plameny begins like Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, only to end in gentle sounds of the glockenspiel and the celesta, which initially bring to mind the operas of Richards Strauss and then – of his not always inspired numerous imitators. In the middle it is possible to find literally everything – from almost line-for-line quotations from Berg’s Wozzeck to New Orleans jazz inspirations and an archaising pastiche in the style of Szymanowski. Schulhoff treats the human voice in Plameny in a strictly instrumental manner: perhaps the only truly “operatic” fragment in the work is La Morte’s solo in the finale of the tenth scene: with a moving glissando of the mezzo-soprano at the end of the phrase “salvation is so far away again”.

I have to do justice to Jiří Rožeň, who managed to keep the sometimes unruly musicians of the Prague orchestra in check throughout the opera. Among the soloists the singer who deserved the biggest applause was the Norwegian Tone Kummervold, underestimated by the audience, who in the thankless role of La Morte showed the full range of now nearly obsolete vocal techniques. A very decent performance came from the female chorus of Shadows, but the performers of the main roles were disappointing, which is especially true of Denys Pivnitskyi as Don Juan, a singer who is not very musical, though gifted with a healthy and strong tenor. Slightly more satisfying was the soprano Victoria Korosunova in the multiplied role of the seducer’s previous mistresses. However, I can hardly blame the singers, as the chaos on stage was primarily caused by Calixto Bieito, a director who after a few phenomenal productions in the early days of his career lost his inspiration completely and has been frittering away his talent ever since. I would advise those of my colleagues who compare Bieito’s concepts to Luis Buñuel’s to go and watch some of the latter’s films again and refresh their memories of their youth. All in all, Plameny turned out to be a beautiful catastrophe giving us hope that Schulhoff’s forgotten work would eventually return to the stage for good – hopefully in a better thought-out staging.

Jan Jirasky. Photo: Marek Olbrzymek

However, Brno did not live by opera alone. During these four days, I also managed to form an opinion (a very favourable one) on the Brno Children’s Choir under the direction of Valeria Mat’ašová and the mixed Kühn Choir, which fared slightly worse under the direction of Jakub Pikla; admire the stylish playing – reminiscent of Rudolf Firkušný’s artistry – of Jan Jirasky, a professor at the Brno Academy of Music and an outstanding specialist on Janáček piano music; and contemplate the condition of contemporary piano playing after a recital by Linda Lee, winner of this year’s Janáček Competition. Lee is technically phenomenal, but completely unaware of the meaning of the music, which pours from her fingers like perfectly round and clearly artificial pearls.

Still, I will go back to Brno, the city where Janáček spent over forty years, created his biggest masterpieces and to this day has not let himself be forgotten.

Translated by: Anna Kijak