The constantly-repeated attempts to prove the superiority of Wagner’s output over Verdi’s œuvre (or vice versa) are condemned to failure from the outset. In the meantime, it is worthwhile to point out the similarities linking the composers, which are more than significant and tell us not so much about them in themselves, as about the era in which it was their lot to live. Born the same year, both were carried away by slogans of national unity and were equally disappointed with the fruits of the Springtime of Nations. Both were bitten by the bug of French grand opéra in their youth, and tried to allude to it in their works – in a frequently surprising, but always non-obvious manner. In the same year, 1859, they wrote works that grew out of their œuvre like dead-end branches of evolution – beautiful ‘black sheep’ that stirred up more in subsequent music history than in their own artistic careers. At that time, Wagner wrote Tristan. Verdi wrote Un ballo in maschera – living proof of the effectiveness of mixing styles as a vehicle for dramatic action and construction of complex human portraits using purely musical means. Both almost got to the heart of the matter, and then moved off in another direction, as it were overawed by how on-the-mark their activities turned out to be.

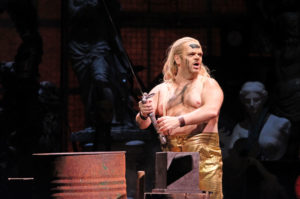

So it was all the more enthusiastically that I took the opportunity to get to Der Ring des Nibelungen in Karlsruhe via a somewhat roundabout route, passing through the Opéra national de Lorraine in Nancy along the way. The new staging of Ballo, prepared in co-production with the Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Angers-Nantes Opéra and Opera Zuid in Maastricht, is a decidedly better match for this place than David Himmelmann’s staging of Kát’a Kabanová. The theatre in Nancy – hidden behind the 18th-century façade of the bishop’s palace, with the rich, historical-looking decoration of its reinforced concrete interior walls – is itself, after all, a building in costume, an edifice pretending to be something completely different. The production’s creators – Flemish stage director Waut Koeken, recently named executive director of the opera in Maastricht, and stage designer Luis F. Carvalho, a Portuguese man who has resided in London for nearly 30 years – went all out with the suggestion of theatre-within-theatre contained in the opera. Their Ballo plays out more or less in the era when the work was written, though the characters have had their original identity ‘restored’ from Scribe’s libretto to Auber’s opera Gustave III, which served as a model for Antonio Somma. A quite risky endeavour, especially since the production team decided to make references in a few scenes to the creators’ problems with censorship (for example, stylizing Gustavo as Napoleon III, who narrowly escaped falling victim to an assassination attempt that resulted in further intervention in the libretto from those days’ guardians of political correctness; and in the final account, in the breaking off of the creators’ collaboration with the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples). So instead of the Earl of Warwick in Boston from the times of Charles II, we got the king of Sweden in a 19th-century tailcoat, who dies at the hands of Anckarström not at the Stockholm Opera, but rather in San Carlo – for the final ball scene plays out against the background of the ceiling of the Neapolitan opera house, framed by rows of box seats like a stage proscenium. The action of the entire opera, furthermore, plays out as part of a peculiar performance within a performance – either on a stage shown onstage, or in the wings of said stage – forming a dual communication among the fictional characters, as well as between the singers and the audience. A procedure as old as the world itself – and that, executed masterfully, all the more so that the production team ensured not only beauty of costumes and scenery, but also believability of theatrical gesture.

Un ballo in maschera. Photo: Opéra national de Lorraine.

In the otherwise quite aptly-chosen ensemble, the most doubts were raised by the creators of the two lead roles. The experienced Stefano Secco (Gustavo) sang with a tired voice, strained and unattractive in timbre – and to make things worse, he did not succeed in lifting the weight of his character, who was missing both royal majesty and ‘solar’ ardour in his feelings for Amelia. The latter (Rachele Stanisci), in turn, was lacking in the technique necessary to meet the difficult demands of her role as the king’s beloved. Gifted with an otherwise well-favoured soprano, the Italian battled an excessively wide vibrato, closed high notes and ill-blended registers for the entire performance; she was able, however, to smooth out her vocal deficiencies with fine interpretation, especially moving in the Act III aria ‘Morrò, ma prima in grazia’. Oscar was played by Hila Baggio, impressive in freshness of voice and lightness of coloratura, but not too convincing in terms of character: instead of reflecting the ‘flighty’, hidden side of Gustavo’s personality, she played the role of the royal jester. About the remaining soloists, I can speak only in superlatives. Ewa Wolak sang Ulrica with a most genuine contralto – velvety in the middle, open and intonationally secure at the top, with an almost tenor-like sound in the low register. More importantly, however, she built this mysterious character with taste and an unerring feel for style, confirming that this is one of the most versatile singers in her unusual voice category. Giovanni Meoni (Anckarström), despite now slightly ‘smoky’ high notes, can still be considered a model Verdi singer – his superbly-placed baritono nobile is enchanting not only in softness of phrasing, but also in perfect understanding of the text and feel for the peculiar idiom. In the roles of the evil conspirators, Emanuele Cordaro (Horn) and Fabrizio Beggi (Ribbing) came out superbly – especially the latter, gifted with a sonorous, beautifully open bass and superb stage presence. The whole was complemented by the splendidly-prepared choir and the orchestra, which – under the baton of Rani Calderon, music director of the opera in Nancy – played in a truly inspired manner: with finesse and a rounded sound, pulsating in the rhythm of the Verdi phrase and not losing the tempo of this extraordinarily complex narrative even for a moment.

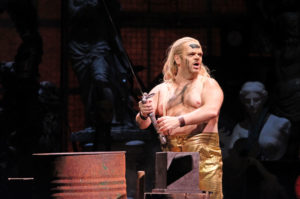

Das Rheingold. Matthias Wohlbrecht (Loge). Photo: Falk von Traubenberg.

The day after the performance of Un ballo in maschera, I completely immersed myself in the world of Der Ring des Nibelungen at the Badisches Staatstheater. The leap was supposed to be reasonably gentle – after a visit to see Die Walküre in December 2016, I knew more or less what to expect of the whole cycle, which in line with the latest fashion was realized by four different stage directors – in this case, rising stars of the international stage. As much as Un ballo in maschera is a perfect match for the eclectic edifice of the Nancy opera house, the timeless Ring, suspended between two worlds, appears to fit perfectly into the Modernist space of the theatre in Karlsruhe. After the almost ecstatic experiences of nearly a year and a half ago, I was at least certain that musicians would not disappoint. I did not expect, however, that Die Walküre – about which I had, after all, reported more or less serious reservations – would remain the most deeply thought-out and best-polished segment of the Ring in theatrical terms. And what is worse, the only one in which the production team managed to get to the heart of the Wagnerian myth. Das Rheingold and Siegfried could be characterized as proper, sometimes witty, but basically quite banal director’s theatre. Götterdämmerung proved the stage director’s unparalleled arrogance – all the more horrifying that in terms of technique, the performance was basically flawless. The director knew what this masterpiece is about, and with a cruelty worthy of a barbarian decided to torture it to death.

Die Walküre. Peter Wedd (Siegmund). Photo: Falk von Traubenberg.

Das Rheingold promised to be quite a good show. David Hermann came up with the idea to ‘summarize’ the entire Ring in the introduction, weaving key motifs from its subsequent parts into Wotan’s gloomy visions. Unfortunately, led by his unerring instinct as a German post-dramatic director, he saddled his concept with an array of stereotyped solutions played ad nauseam – starting with the introduction of additional characters, and finishing with a partial ‘update’ of the plot that boils down the initial conflict to a business issue between a dishonest investor and two disappointed building developers. Fortunately, the down-to-earth world of Wotan-the-businessman clashes with the fantastic world of myth, which at certain moments creates quite convincing dramatic tension – not sufficiently powerful, however, to provide an effective counterweight to the tension contained in the score itself. In this combination, the dreamlike, symbol-laden Die Walküre directed by Yuval Sharon comes out more than positively. I refer interested parties to my previous review: I shall just add that in a few places, Sharon introduced corrections, generally justified, though I am not entirely sure if replacing the allegorical scene of Siegmund’s death, in which the son dropped dead at his father’s hand, with a literal duel scene with Hunding, was indeed a change for the better. Siegfried in Þorleifur Örn Arnarsson’s rendition again moves in the direction of banal reinterpretation of the myth – in other words, intergenerational conflict and the defeat of tradition in the battle with modernity. Mime’s forge is a peculiar rubbish heap of history, cluttered with a host of objects evoking the most diverse associations with German culture. In this mess, Siegfried carefully hides the attributes of teenage rebellion. Similar contrasts form the basis for the production’s entire concept, which essentially boils down to a confrontation of several different visions of theatre. In the finale, a Siegfried like something out of a comic book awakens a Brünnhilde taken, as it were, straight from a cheap oleograph. All in all, nothing special, though I must admit that the idea for the sword scene, in which Siegfried waits for Nothung to forge itself, contains much psychological truth and does, in a way, get to the heart of Wagner’s message.

Siegfried. Erik Fenton (Siegfried). Photo: Falk von Traubenberg.

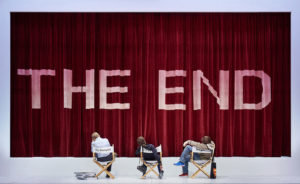

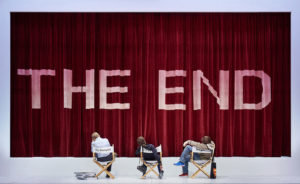

I am a bit afraid I shall lose my temper describing the Götterdämmerung with which Tobias Kratzer regaled us, so I shall keep this short. For the three Norns, characterized as the stage directors of the preceding parts of the Ring, the idea for finishing off the cycle breaks off as suddenly as the rope of destiny. Which does not mean that the three directors (en travesti) will disappear from the stage for good. They will appear every now and again – as Valkyries, as Rhine maidens, as a women’s chorus – desperately trying to save a situation that has spun out of their control. And indeed, it has. Siegfried vows Brünnhilde love until death them do part… then starts to masturbate; Alberich gets the feeling that he will have something in common with Klingsor from Parsifal… and proceeds to castrate himself; Grane the horse appears onstage first alive, then dead (fortunately in the form of a mannequin), and finally gets eaten during a jolly grill party; the magic elixir turns out to be vodka, so Siegfried falls in love with Gudrun while drunk – and so on, until the final scene of mass destruction. Which boils down to Brünnhilde putting everyone straight: she herself sits down on the director’s chair and takes the action back to the point of departure. In other words, to the moment before Siegfried dug himself out from between the sheets and went out into the world. In my lifetime, I have seen stagings less in agreement with the letter of the libretto and the score. But I have never in my life seen a staging so vulgar that there were moments it took away my desire to listen to the music I adore. Kratzer managed to pull that off.

My grudge against him is all the greater that in musical terms, the Karlsruhe Ring is truly one of the best in the world. The Badische Staatskapelle under Justin Brown plays with verve and enthusiasm reminding one of Clemens Krauss’ interpretations from the golden years of Bayreuth – with a clear, saturated sound, masterfully diversifying dynamics, meticulously weaving textures, clearly layering sonorities. The soloists toughened up and, in most cases, built characters finished in every inch. This time Renatus Mészár, a singer of extraordinary intelligence and musicality, was completely in control of his velvety bass-baritone and reflected all of the stages in the fall of the king of the gods: from anger, to despair, to exhausted passivity. Heidi Melton as Brünnhilde in Die Walküre was almost perfect; while her dark and rich soprano betrayed signs of exhaustion in Siegfried, it regained its vigour in Götterdämmerung, though not quite totally open high notes did appear here and there. Katharine Tier got better and better with each performance – a quite good Fricka in Das Rheingold and Die Walküre; heartbreaking with Erda’s sad prophecy in Siegfried; in terms of voice and character a daring Norn, Waltraute and Flosshilde in that wretched Götterdämmerung. The juicy and youthful, though in some people’s opinion a bit over-vibrated soprano of Catherine Broderick (Sieglinde) created an ideal counterweight to the ardent and, at the same time, surprisingly mature singing of Peter Wedd in the role of Siegmund. His Heldentenor is slowly ceasing to be jugendlich: with evenly-blended registers, tremendously sonorous, supported by a large wind capacity and, at the same time, dark and increasingly authoritative in sound, it gives him all of the predispositions necessary to perform the heavier Wagner roles, and opens up the path to a few other roles in the standard Helden-repertoire. Wonderful supporting characters were created by Avtandil Kaspeli (especially as Hunding) and Jaco Venter (Alberich).

Götterdämmerung. Katharine Tier (Waltraute, First Norn, Flosshilde), Dilara Baştar (Second Norn, Wellgunde), An de Ridder (Third Norn). Photo: Matthias Baus.

I have said nothing yet about Siegfried: in the third part of the cycle, Erik Fenton – gifted with a voice relatively small for this role, but well-favoured and beautifully, broadly phrased – did quite a nice job. In Götterdämmerung, I was not thrilled with Daniel Brenna, a singer whom one can fault for basically nothing – except for this: his interpretation leaves the listener perfectly indifferent. This is the first thing for which I fault the cast of this Ring. After a Siegmund with a voice like a bell and a role built from the foundations up to the roof, we got two Siegfrieds who did not equal him either in volume or in skillful shaping of their characters. I have more serious reservations about Loge. I do not know whose idea it was to give this role to an outstandingly character tenor – the otherwise technically and theatrically superb Matthias Wohlbrecht, who sang a daring Mime in Siegfried. After all, Loge is a beautiful, dangerous and scarily wise being. In a way, he is the axis around which the entire narrative revolves, a deity ‘almost ashamed’ that he has to identify with the other gods, a creature able to command respect even from Wotan. In the subsequent parts of the cycle, he is a great absence whose seductive voice will thenceforth be heard only in the orchestra. It is not without reason that Furtwängler and Böhm cast Windgassen in this role – and that, at the peak of his vocal powers.

But enchantment won out after all. Both in Nancy, and in Karlsruhe. At two theatres with such superb ensembles, such sensitive conductors and such a faithful, music-loving audience that they will yet survive more than one fashionable stage director, and more than one little casting error.

Translated by: Karol Thornton-Remiszewski