Elektra in the Land of Cockroaches

People of Westphalia joke that tourists do not have to buy a new map of Münster: they can get by with a copy of one of the sixteenth-century copperplates with a panorama of the city. The layout of the streets has not changed for hundreds of years, even after the Second World War, when more than ninety per cent of Münster’s Old Town lay in ruins following Allied air raids and the subsequent artillery attack. Münster is one of the few German cities which did not implement a modernist reconstruction plan – with a network of car-friendly thoroughfares and with isolated historic buildings emerging from a sea of modern edifices. There were disputes, but eventually the idea of raising the city from the ruins almost intact won: whether out of respect for the city’s turbulent history or because of the ambiguous attitude of Bishop Klemens von Galen, who thundered from the pulpit just as loudly against Nazi crimes against the civilian population as he did against the carpet bombings of German cities towards the end of the war.

One of the few concessions to modernist architectural thought is the building of the Theater Münster, just a several minutes’ walk from two of the city’s most famous religious buildings: the monumental, late-Romanesque St. Paul’s Cathedral, known in Poland primarily as the venue of the premiere of Krzysztof Penderecki’s St. Luke Passion, and the gloomy Gothic St. Lambert’s Church, on the tower of which it is still possible to find the frightening iron cages where the remains of the murdered leaders of the theocratic Anabaptist commune were displayed in 1535. The building, designed by four young German architects on the initiative of Hermann Wedekind, the then director of the municipal theatre, caused a sensation across Europe. Opened in 1956, it was the first modern theatre in post-war Germany. It combined bold spatial solutions – primarily a paraboloid stage tower and a perfectly designed three-tier auditorium ensuring intimate contact with the performers even for spectators from the farthest rows – with respect for the city’s cultural traditions. The new structure encompassed not only the remains of the old theatre and music school, but also the trees that survived the wartime conflagration and were included in the plan of the inner courtyard.

Rachel Nicholls (Elektra). Photo: Martina Pipprich

With time the furore died down, but solid craftsmanship has remained, since 2017 under the leadership of Golo Berg, who took over the musical directorship of the company from the Italian conductor Fabrizio Ventura. In January last year Katharina Kost-Tolmein, a pianist and a graduate in musicology and philosophy from the University of Heidelberg, was appointed general director and opened her first season at the Theater Münster with a production of Ernst Křenek’s Leben des Orest, having previously been at the helm of Theater Lübeck for seven years. Nearly one year later she decided to return to the motif of destructive revenge among the Atrides by staging Strauss’ Elektra – the first fruit of the composer’s collaboration with Hugo von Hofmannsthal and his most daring excursion into radical musical modernism.

Kost-Tolmein declares herself to be an advocate of theatre that is “modern and open to experimentation”. I had an opportunity to see what this meant in practice five years ago in Lübeck, where I travelled to see a performance of The Flying Dutchman featuring a very decent cast and brilliantly conducted by Anthony Negus, but in a staging by Aniara Amos that was inept to the point of ridiculousness. I suspected that I might experience something similar in Münster and I was not wrong. Although Elektra, as presented by Paul-Georg Dittrich, was not as visually off-putting as the Lübeck Dutchman (perhaps thanks to Dittrich’s collaboration with the experienced Christoph Ernst, who was responsible for the set, costume and lighting design), it did expose all the sins of the German Regieoper, revealing few of its virtues in exchange. Elektra may be Richard Strauss’ most coherent stage work. It virtually begs to be directed, especially bearing in mind the powerful influence on the dramaturgy of Elektra, as well as the earlier Salome, of the ideas of Max Reinhardt, who categorically opposed the interference of politics in the sphere of art. Yet Dittrich turned Stauss’ one-act opera into a veritable orgy of political theatre, combining without any rhyme or reason elements of agitprop and old-fashioned Zeittheater with unbearably simplified social criticism of the Castorfian and Polleschian kind.

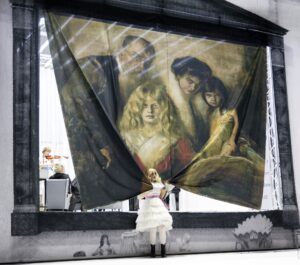

Margarita Vilsone (Chrysothemis), Rachel Nicholls, and Hasti Molavian, Maria Christina Tsiakourma and Katharina Sahmland as Maids. Photo: Martina Pipprich

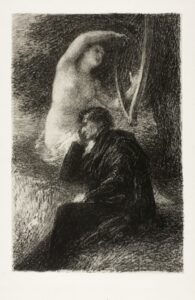

Thus an operatic study of revenge was transformed into grand reckoning with the German past and present – with the protagonists portraying increasingly new and increasingly bizarre characters. The frantic journey from the decline of the Hohenzollern dynasty, through the Third Reich and the turbulent 1960s, to the Tatort Münster crime series, the activities of the NSU terrorist militia and cheap journalistic allusions to the Merkel and Schröder governments, was accompanied by an almost constant movement of the revolving stage. The performers rushed to and fro, led by Elektra, who first swapped her costume of a predatory Lolita for an SS uniform, and later dressed up as Romy Schneider portraying Elisabeth of Bavaria in the film Sissi. A detailed description of this pandemonium is beyond my patience and the framework of this review. Suffice it to say that an alphabetical guide to the director’s tropes took up two pages of small print in the programme booklet. Only the Maids, dressed by Ernst in surprisingly realistic exoskeletons of the female oriental cockroaches (Blatta orientalis), retained a relatively unified identity.

I always admire artists who in such harmful working conditions simply do their job and do it well. I came to Münster primarily because of Rachel Nicholls, whose career I have been following closely since her decision to gradually move towards dramatic soprano roles. Someone once said that Salome needed an adolescent Isolde and Elektra – a Brunhilde that is not much older. Nicholls has both Isolde and Brunhilde in her repertoire, and in both roles she comes close to the aesthetics that not only Wagner, but also Strauss would have preferred. Her voice is relatively bright and sounds really youthful, does not need to be forced in the excellent acoustics of the Theater Münster, and given the singer’s extraordinary intelligence, tremendous musicality and acting skills it becomes a perfect vehicle for the madness tormenting Elektra. Nicholls’ interpretation is definitely closer to Rose Pauly’s portrayal from the late 1930s than to the legendary interpretations of Inge Borkh and Birgit Nilsson – which should, in fact, be regarded as a complement. Her Elektra is both fragile and terrifying, and, most importantly, develops as a character, from the powerful monologue “Allein! Weh, ganz allein” to the eerie “Ob ich die Musik nicht höre? Sie kommt doch aus mir” in the finale of the opera. She found a worthy partner in the Chrysothemis of Margarita Vilsone, a singer with a resonant, rich and very warm soprano. Helena Köhne was an outstanding Clytemnestra, with a contralto appropriate for the role, beautifully developed and superbly controlled, but the artist was decidedly less committed as an actress, which is entirely understandable given that the director turned her into an Angela Merkel. Singing in an otherwise handsome baritone, Johan Hyunbong Choi (Orestes) failed to build a convincing character, which Aaron Cawley, surprisingly, managed to accomplish in the brief part of Aegisthus. It is worth paying attention to this singer, who found himself in Dittrich’s staging in place of the indisposed Garrie Davislim: the young Irishman has the makings of an interesting Heldentenor with a golden, baritone tone. Worthy of note among the rest of the cast were Maria Christina Tsiakourma, Hasti Molavian, Wioletta Hebrowska, Katharina Sahmland and Robyn Allegra Parton, who made up a perfectly integrated, though sonically diverse, ensemble of five Maids. The whole was masterfully controlled by Golo Berg, who skilfully emphasised both the novelty of the work (Elektra’s demonic death “waltz”!) and the often surprising lyricism of the score.

Margarita Vilsone and Rachel Nicholls. Helena Köhne (Clytemnestra) in the middle background. Photo: Martina Pipprich

I left the theatre delighted with the quality of the performance, but unable to shake off the thought of how much more beautiful and terrifying it would have been, if it had been without the swastikas, burning Hindenburgs and ubiquitous cockroaches. I hope that no fan of theatre that is “modern and open to experimentation” will commission Dittrich to transfer Kafka’s Metamorphosis to the stage.

Translated by: Anna Kijak