An Operatic Treasure Trove

Whenever high art ceases to be associated with high style and begins to be associated with high-handedness, it stumbles, tumbles down several storeys and becomes an object of ridicule. A few years ago a certain musical institution in Poland – an institution with otherwise beautiful traditions – decided to outsalzburg Salzburg and announced that “casual elegant” would be a mandatory dress code within its walls. Garments to be banned from that moment on included jeans and sweaters. The initiative was rightly mocked and the organisers quickly abandoned the “rules” they had so hastily formulated. The festival remained a democratic event, where we are more likely to meet true music lovers in freshly laundered jeans and tasteful sweaters than bored officials in suits smelling of mothballs.

This is not surprising: philharmonic halls and other concert venues have long been reaching out to their audiences with increasingly broad and varied repertoires – from medieval music to contemporary works, played and sung by various ensembles and artists cultivating very different performance styles. Listeners have a lot to choose from and can without any major difficulty expand their knowledge thanks to analyses of works in programme booklets, radio programmes, broadcasts and internet streams, meetings with musicians as well as comparisons of interpretations presented live with the rich and easily accessible discography.

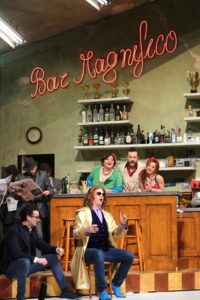

Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice at the Wrocław Opera. Photo: Krzysztof Bieliński

Potential opera goers are in a far less comfortable situation. Putting on a full staging brings with it huge costs, incomparable to the costs of organising an “ordinary” concert. This is also why it is difficult to access complete opera recordings, not to mention video recordings of performances. Ordinary music lovers prefer to save up for a ticket to a concert hall rather than risk going to the theatre, where they will see their beloved Tosca in costumes and sets that have nothing to do with the musical concept. Ordinary theatre lovers prefer to see a performance of a play in which they will understand every word spoken on stage and will not have to wonder why the gentleman on stage is still singing a quarter of hour after he was mortally stabbed in the heart. Ordinary snobs will be bored for a much shorter time in a concert hall, from which they can escape between movements of a work, for example.

Opera as a theatre genre is in crisis all over the world, but there are very few countries where the crisis is as worrying as it is in Poland. Successive rumours about the death of opera, spread by philosophers and culture scholars for at least one hundred years, have turned out to be as exaggerated as the news of the death of Queen Bona from Tuwim and Słonimski’s unrivalled satire. The convulsions of the alleged agony only signalled a need for a through revamping of the convention. The process is painful everywhere, but is beginning to produce results: most “revitalisation” work is done in the purely theatrical layer, the approach to which increasingly varies, beginning with attempts at historical reconstruction of old productions, through references to the classics of modernist theatre and ending with progressive and often invasive practices of Regietheater. All over the world there are disputes– often fierce – over the validity of staging concepts, but no one mocks the theatrical nature of operas themselves. No one mocks librettos, in the logic of which “no one in their right mind will believe”, as one Polish director put it. No one remains indifferent to the practice of making cuts, changing the order of the various “numbers” in the score and introducing additional sound effects not provided for by the composer – some sing loud praises of such interventions, others protest until their last breath. No one thinks, as another Polish artist put it, that they are watching “a silly story”, no one feels “blackmailed by the very respectability of the operatic art”.

Despite various experiments and sheer iniquities committed by directors today against the living and lively body of this form, despite the demise of true stars and decline of the old art of singing – opera per se is doing better and better in the postmodern reality. It satisfies people’s longing for fairy tales, it allows them to escape into the land of magical thinking, provides a release for emotions unavailable in the dark, popcorn-smelling cinema room. For ordinary consumers of Western culture going to the opera is as important as element of spiritual nourishment as reading books and watching various shows on Netflix. Well-behaved Europeans will admit to not knowing Oscar-winning films rather than admit to not being familiar with the intrigue of Carmen or Un ballo in maschera.

Verdi’s Nabucco, the open-air superproduction at the Wrocław Opera. Photo: Maciej Suchorabski

In Poland, on the other hand, opera goers are getting increasingly polarised. On one extreme we have fans of opera stars and the commotion which usually accompanies their performances, and on the other – enthusiasts of spectacular, Hollywood-style productions by fashionable directors. Interestingly, representatives of both extremes care little about the phenomenon of operatic music as such. The former are quite satisfied with the celebrities showing up and singing, while the latter treat the musical layer of a production as a kind of soundtrack to a non-existent film. Between these two extremes wanders an increasingly small, increasingly lonely and often ridiculed group of fans who really cry over the fate of the wretched Halka, really know Nabucco inside out and really can appreciate the quality of a performance – sometimes in comparison with many forgotten archive recordings and in the context of changing interpretation practices.

What has brought this on? After all, the parents of my mates from primary school – even if they did not want to or were ashamed to go to the opera – knew who Callas, Chaliapin and Caruso were. After all, we all laughed in front of our television sets when the “famous Siamese tenor” sang Jontek’s aria in Stanisław Bareja’s comedy series and we heard a translation back into Polish (“My life, though young, is sad, for there is a grudge in my heart, I don’t accuse anyone in particular except for my girl…” etc.). After all, the post-war premiere of Lohengrin at the Warsaw Opera must have also been a great social event, if Jeremi Przybora alluded to it in Kabaret Starszych Panów (Elderly Gentlemen’s Cabaret).

I will not repeat the clichés about long term effects of the decline of music education in schools. But I will weigh in with my opinion about the unreasonable policy of the directors of many opera companies in Poland, who during the transformation period looked up to the West, without taking into account the distinct determinants of our culture. Having concluded that we could not afford the German-Austrian repertoire model, in which productions – created by soloists, chorus members and orchestra musicians working well together on a daily basis – were added to the repertoire for many seasons, they opted for the Italian stagione system. Yet putting on an expensive production featuring singers contracted especially for the purpose and then presenting just three or four performances has little in common with a genuine stagione, in which a production is presented even a dozen or so times, is preceded by months of intense rehearsals and after a while is revived at home or moves to another opera house.

Beethoven’s Fidelio at the Wrocław Opera. Photo: Krzysztof Zatycki

The Wrocław Opera is one of the last companies in Poland still trying to stick to the repertoire system – which is beneficial to both connoisseurs and novices taking their first steps in the magical world of opera. Over the last two seasons things have sped up: the company has added Italian bel canto works, neglected in Poland, to its repertoire; there have also been more contemporary works; young directors previously not allowed on the big stage have been given a chance; works which cannot yet hope to attract crowds have been given meticulously prepared concert performances. The Wrocław Opera is building its repertoire wisely, respecting the audience’s varied tastes: it alternates “traditional” productions with examples of well thought out although sometimes controversial Regietheater. It invests in the education of children and adults. It invites the curious among them backstage and to various technical rooms. It goes out with music into the urban space.

In the upcoming season it will transfer to the opera house two of its open-air superproductions: Verdi’s Nabucco directed by Krystian Lada and Gounod’s Faust directed by Beata Redo-Dobber. It will present a new staging of Moniuszko’s Halka. It will tackle Phantoms in a production entrusted to Jarosław Fret, the founder of Teatr ZAR and director of the Grotowski Institute. It will present Mozart’s Don Giovanni after a concept by André Heller Lopes, one of the most interesting opera directors in Latin America, who for several years has been successfully presenting Janáček’s operas in Brazil. Bel canto enthusiasts will be served a concert performance of Donizetti’s La fille du régiment, fans of superproductions – a new production of Traviata, advocates of intergenerational education – Zygmunt Krauze’s family opera Yemaya, lovers of the Terpsichorean art – classical Giselle choreographed by Zofia Rudnicka and Ewa Głowacka as well as two modernist ballets by Stravinsky, Card Game and The Rite of Spring, to be presented by Jacek Przybyłowicz and the Swedish dancer Sigge Modigh.

There will be a lot to choose from, especially given the fact that the company’s repertoire will also feature productions premiered in its extremely busy last season, alternating with the best productions from previous seasons. Soon Wrocław opera lovers will start exchanging jokes like those of the Opera North patrons who regularly compile lists of New Year’s resolutions for the protagonists of operas presented in Leeds. Last season Fiordiligi and Dorabella made an appointment with an ophthalmologist, while Siegfried promised Brünnhilde he would spend more time with her at home. Opera can teach, entertain and move to tears – provided you are in touch with it on a daily basis.

Translated by: Anna Kijak