The Trauma of the Volsungs

A coherent Ring realized by four stage directors? Never happened yet. Now, the idea of entrusting each part of the tetralogy to a different production team is in itself no novelty: it started with Oper Stuttgart’s famous endeavour, begun in 1999, whose participants included not only four stage directors, but also three Wotans, three Brunnhildes and two different Siegfrieds. The only link tying this dubious ‘cycle’ together was conductor Lothar Zagrosek. Nine years later, Aalto Musiktheater in Essen followed a similar path, with an even less convincing artistic result: this time, the risky mission of giving the whole thing musical sense fell to Stefan Soltesz. The management of the Badisches Staatstheater in Karlsruhe declared, however, that its new staging of the Ring – prepared by different production teams – will make up a logical whole and will not obscure the message of Wagner’s masterpiece. Responsibility for all of the shows has been taken by British conductor Justin Brown, who has been the theater’s music director for eight years, and been highly rated by German critics for, among other things, his superb preparation of the renewed production of Parsifal under stage director Keith Warner, as well as last year’s première of Tristan und Isolde in the rendition of Christopher Alden.

Unfortunately, I did not manage to get to Das Rheingold, which premièred in July. I do, however, intend to go to Karlsruhe for the subsequent parts of Der Ring des Nibelungen, and certainly will see and hear the festive staging of the cycle in its entirety, slated for 2018. The prologue under stage director David Hermann received generally very positive reviews. After the première of Die Walküre (11 December), realized by a team comprised of Yuval Sharon (stage director), Sebastian Hannak (stage design), Sarah Rolke (costumes) and Jason H. Thompson (video), opinions were divided. I understood that a difficult task awaited me. Some of the dress rehearsal pictures indeed augured the worst. However, I knew Sharon’s earlier stagings from extensive excerpts circulating online (among others, his superb rendition of The Cunning Little Vixen with the Cleveland Orchestra, as well as of John Adams’ opera Doctor Atomic, presented in Karlsruhe two years ago and honoured with the Götz-Friedrich-Preis), which spoke decidedly in favor of his craftsmanship. I found out for myself in person, at the second part of the Ring cycle, that in the case of Die Walküre, the stage director’s imagination had lost its battle with Hannak’s trite, though to a certain extent functional stage design and Thompson’s not-always-apt projections.

Catherine Broderick (Sieglinde) and Peter Wedd (Siegmund). Photo: Falk von Traubenberg.

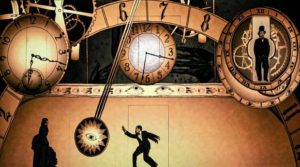

Yuval Sharon’s idea for the second part of the tetralogy is quite clever and consistently leads the cycle in the direction of the ‘Icelandic’ Siegfried, which is being prepared for June of next year by Þorleifur Örn Arnarsson. From the beginning, a chill wafts from the stage, bringing to mind associations with the Poetic Edda and the ultimate source of Die Walküre: the 13th-century Saga of the Volsungs. Sharon builds a mythic world from an array of anachronisms, symbols and archetypes placed outside of time and the ‘historical’ conditions of the narrative – on a similar principle to that of Pasolini, who confronted Balkan rites of passage with the aesthetics of Byzantine temples in Cappadocia in his Medea. Hunding’s gloomy home takes the form of a long corridor with several doors which not only link the interior with the exterior, but also turn out to be gateways to other dimensions. From the moment the wounded and exhausted Siegmund stumbles in, bringing with him a cloud of snow, the doors will time after time open and slam shut, sometimes even resisting the protagonists’ attempts to open them. On the ‘other side’, we see semiconscious, fleeting images from the past and harbingers of the cursed siblings’ further fortunes: pictures from Siegmund and Sieglinde’s childhood, figures of the musicians introducing successive leitmotifs, Sieglinde’s memories of her grim wedding and the visit of the one-eyed guest that torment her. The ominous shadow of Hunding, the ash tree with a sword stuck in its trunk, the trees that almost imperceptibly turn green at the sound of Siegmund’s ecstatic song – appear in the form of understated but distinctive light projections. The costumes do not allude to any particular era; their task is to characterize the personage wearing them. The barefoot, wolf skin-clad Siegmund is an archetype of the outcast, the mysterious visitor from nowhere. Hunding’s dullness and primitivism is underlined with the pretentious attire of a contemporary parvenu. Clothed in a simple dress, Sieglinde is a nobody until Siegmund gives her an identity by wrapping her in animal fur.

This all represents a bit of excess on the stage director’s part; nonetheless, Sharon does shape a very convincing narrative in Act I: the protagonists join in a process as brilliant as it is painful of working through childhood trauma. They move from fear, through shame and disbelief, to ecstasy – but in the dark corners of their souls and of Hunding’s home lurks the sadness of the Volsungs and a vague premonition of the end being near. This is the first part of the tetralogy in which people appear: at the same time, it is the last one in which the people are moving, weak, inspiring reflexive sympathy despite the breaking of marital vows and the violation of the incest taboo. The stage director has wrung out every last drop of the potential contained in this part. Act II went a bit worse for him; for the most part, it was dominated by stairs linking the world of mortals with the domain of the gods. The steps gliding alternately down and up turn out to be an apt metaphor for the frustration of Wotan, who is continually going in the wrong direction and thereby de facto standing still (the superb marital quarrel scene between the ruler of Valhalla, a substantially-built man with the appearance of a California gangster; and Fricka, taken as it were straight from the film The First Wives Club). They do not work theatrically at all in Wotan’s great confession or in his later dialogue with Brunnhilde – the dramatic power of this segment has clearly exceeded the capacity of Sharon, who fortunately rehabilitates himself at the end of the act with Siegmund’s death scene, beautiful and even naïve in its simplicity. At this point, time slows down, and then stops – as in the score – and Brunnhilde’s horror is exceeded only by Wotan’s despair.

Renatus Mészár (Wotan) and Heidi Melton (Brunnhilde). Photo: Falk von Traubenberg.

In Act III, everything breaks down. The idea to replace the ride of the Valkyries with the crazy flight of eight virgins on paragliders might even work if the accompanying animation were either less literal or, on the contrary – breathtaking. Meanwhile, it comes out like a presentation using the free version of PowerPoint. I would have believed in the boundless polar landscape and empty sky over the land of the Icelandic sagas if I had not seen onstage something that looked like a scale model of an atomic bomb shelter against a sky-blue background. I would have listened differently to the shocking battle of the father with his beloved daughter if the stage director had given the two of them any acting tasks at all (aside from Wotan’s tapping the wooden boards of the stage with a spear). Wonder of wonders, I was not at all scandalized by the concept to encase Brunnhilde in a block of ice and surround it with a wall of fire that I would interpret as a ribbon of aurora borealis – what did scandalize me, however, was the cottage-industry realization of this vision, which was the fault above all of the stage designer and the author of the projections.

And now enough complaining, because in a musical sense, the production exceeded my boldest expectations. There were basically no weak points in the cast: in Act II, Ewa Wolak (Fricka) – an excellent singer and superb actress who liberated the entire dramatic potential latent in the delicious fight scene with Wotan – shone with wondrous brilliance with her deep, overtone-rich contralto voice, flawless in intonation and articulation. The Brunnhilde of Heidi Melton, the greatest star of the production, is impressive in the beauty of her voice, superb in its lower and middle register, but too-often constricted in the upper range, which affected in particular the believability of the final ‘War es so schmählich’. I admit to having been more concerned about the debut of Catherine Broderick as Sieglinde – fortunately, my fears turned out to be groundless. Her lovely, full and, at the same time, youthful-sounding dramatic soprano revealed the totality of its values in the ‘Der Männer Sippe’ monologue from Act I. Broderick’s passionate singing, marked by a characteristic light vibrato, blended ideally with the tenor of Peter Wedd (Siegmund), which is growing darker in colour and more extensive in volume over time. His phenomenal phrasing and the peculiar timbre of his voice, in which tenderness fights for the upper hand with plaintiveness, permitted him to create a character that moves one to the core. Add to this his superb technique (in the increasingly powerful ‘Wälse! Wälse!’, he consistently descended the octave with a pearly glissando) and incredible breath control (he took ‘Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond, in mildem Lichte leuchtet der Lenz’ comfortably in one phrase), and we are no longer surprised by the hurricane of applause the audience gave him after Act I. Against the background of the ardent, soaring singing of Sieglinde and Siegmund, I was a bit disappointed with the slightly flawed intonation in the role of Hunding (Avtandil Kaspeli); though on the other hand, his dark, ominous-sounding bass represented a perfect counterweight to the voices of the unhappy lovers. Renatus Mészár (Wotan) created a convincing, multidimensional character of Wotan, even though I sometimes missed a bit of divine authority in his beautiful bass-baritone. It is another matter that in the farewell scene with Brunnhilde („Leb’ wohl, du kühnes, herrliches Kind!”), which is ‘flattened’ by the stage director, if it had not been for the culture of Mészár’s interpretation, I would have died of boredom.

Renatus Mészár and Heidi Melton. Photo: Falk von Traubenberg.

I address separate words of praise to the orchestra of the Badisches Staatstheater under the baton of Justin Brown. I was stupefied already in the first measures of the prologue when I heard the quintuplet sixteenth-notes in the lower strings – played at a tempo worthy of Clemens Krauss and, at the same time, so clear and legible that some wild beast fleeing a storm appeared before my eyes. In turn, the next passage, leading from the ’cello solo with the love motif up to Siegmund’s ‘Kühlende Labung gab mir der Quell’, equaled the most brilliant interpretations of Beethoven’s chamber music masterpieces in its subtlety. In the ride of the Valkyries, they finally managed to balance the proportions between the rhythmic pattern and the melodic line. Brown brought out from the score that most precious of values: the autonomy of the orchestra part, which neither blends with the soloists’ voices, nor accompanies them. It adds, articulates that which is not expressed in words; it discerns what the protagonists do not yet know; it links the divine and human world orders.

I went to Karlsruhe to see a presentation of Die Walküre in a cast comprised almost exclusively of foreigners, prepared musically by a Briton. I wondered all the way there whether what I would witness would amount to bringing wood into the forest. Judging from the audience’s response, Germans are completely ready to have their national treasures dusted off. Perhaps their own interpretations have begun to sound false to them.

Translated by: Karol Thornton-Remiszewski