The Agony and the Ecstasy

Two years ago, the Longborough Festival Opera was the world’s first private opera house to present the entire Ring of the Nibelung in one season. This year, it basically began the worldwide celebration of Tristan und Isolde’s 150th birthday by giving the first presentation barely two days after the anniversary of the world première in Munich. I have written about the Grahams’ endeavour – as beautiful as it was crazy – already previously, so I shall not repeat myself. I shall only explain what drove me to Longborough, for my decision concerning the trip to see and hear that Tristan was made over a year ago, after the Warsaw première of Lohengrin. The performer of the title role, Peter Wedd, provoked mass confusion among our critics. The so-called main trend was populated by his opponents, who were trying to compare his interpretation with the supposedly obligatory model template. From several side trends, voices of admiration reverberated – more often, however, focused on the general manner of building the character than on the enormous, at that time already evident potential of this singer. Intrigued by Wedd’s extraordinary musicality and the beauty of his dark, overtone-rich tenor, I began systematic field research. With pleasure I observed how that voice grew stronger, gaining power and a peculiarly Wagnerian brilliance. I traveled to Longborough hoping that Anthony Negus had managed to fill in the rest of the cast with equal sensitivity, work out a convincing concept for the whole and clothe it in an appropriate sound. Reality exceeded my boldest expectations.

And it had seemed to me that those expectations were, even so, excessive. The stage at Longborough resembles that of a second-rate cinema out in the middle of nowhere. No sophisticated acoustical paneling: spread over the audience’s heads is a roof of corrugated metal supported on wooden rafters. The orchestra pit – as in Bayreuth – is deep and placed almost entirely beneath the stage. The singers follow the conductor’s movements on black-and-white monitor screens hung on the walls of the side loggias. To organize that microscopic stage space, one must have truly enormous imagination, intuition and good taste. All of these things were present, especially in the stage designer (Kimie Nakano) and the lighting director (Ben Ormerod), who put us into the mood of the Tristan myth with a spectacular play of colors and contrast, almost entirely abandoning scenery and superfluous props. Their vision, on the one hand, brought to mind associations with Japanese Nō theatre, where the actors move about an empty stage; and on the other, with Wieland Wagner’s legendary second staging from Bayreuth (1962) – especially in Act III, where a characteristic ‘Celtic’ monolith with a round opening in its upper portion appeared at the back of the stage. Japanese inspirations were also evident in the cut and colors of the costumes, loosely modeled on court attire and warriors’ clothing (Tristan appeared in something resembling a shinobi shōzoku, the traditional clothing of Japanese ninjas). Stage director Carmen Jakobi filled in the whole with economical, indeed ascetic acting gesture, so I have no idea what tempted her, at key moments in the drama (among others, during the love duet from the second act and in Tristan’s death scene), to introduce two dancers, otherwise fantastic, who were supposed to reflect the characters’ ‘Jungian’ subconscious. First of all, this is a solution of a completely different order – for choreographer Didy Veldman appealed not only to Jung, but also to the erotic bas-reliefs from Khajuraho – and secondly, the dance distracted one’s attention from the considerably more interesting symbols contained in Wagner’s music itself. I must admit, however, that in comparison with the visions of Polish stage directors, with their ubiquitous parades of little girls without matches and little boys with gramophones, Katie Lusby and Mbulelo Ndabeni created only a minor dissonance with the rest of this deeply thoughtful staging.

Photo: Matthew Williams Ellis

This is nothing, however, in comparison with the brilliant coherence of Anthony Negus’ musical concept. My fears that the orchestra’s sound would not find its way through the narrow throat of the pit, but rather disappear into the abyss beneath the stage, were dispelled already in the second measure of the prelude, where the legendary Tristan chord appears for the first time. When Tristan’s ’cello motif merged with the oboe wistful Liebeslust theme, I gained certainty that this true master of the baton would balance the proportions even in such Spartan conditions. Even if one felt a certain dissatisfaction with the volume of the strings (Negus was conducting a relatively small ensemble, comprising a total of 61 instrumentalists, distributed about the pit in a German-style arrangement), he more than made up for it with the exceptional beauty of their sound. In terms of style, Negus’ craft can be compared with the most brilliant interpretations of Karl Böhm – and here, I do not at all have in mind barren imitation, but rather an aptness of interpretation flowing from knowledge of the deepest kind. This Tristan pressed on inexorably toward the final ecstasy of the Liebestod, moving forward in strong tempi, energetically, passionately, retaining proper proportions between longing, sensuality and desire for ultimate fulfillment. On the one hand, Negus made ideal use of harmonic (vertical) features; and on the other, he ingeniously impinged upon them with melodic thinking, whereby he built tension so effectively that sometimes this Wagner was no less than painful. Let us add to this a watchmaker’s attention to detail, and we shall find ourselves in seventh heaven.

Over the past year, Wedd’s voice has gone through a metamorphosis surprising even to the careful observer. It has taken on a yet darker colour (in the lower register, it sounded more baritone-like than the singing of Kurwenal), while at the same time retaining ecstatic ardour and heartbreaking lyricism which inclines one to comparisons with the achievements of Max Lorenz at the peak of his career. Aside from this, the singer is tireless: only the greatest masters are able to retain such power of expression and depth of interpretation during Tristan’s death scene. Rachel Nicholls took her first steps as a Bach and Handel soprano; after that, she had the good fortune to come across Anne Evans, who opened up her voice to repertoire of heavier caliber. For Wedd, she turned out to be the ideal partner: physically delicate, almost girlish, but at the same time, warm, passionate, full of emotions brought out by flawless intonation and a perfect feel for phrasing. If it were possible to fault her for anything at all, it would be a not-quite-complete immersion in the role of Isolde, though I am convinced that this, too, will come with time. Nearly all of the other soloists created memorable characters: from the broken King Marke (Frode Olsen); to the distinctive, psychologically complex Brangäne (Catherine Carby) and the touchingly devoted Kurwenal, trying to maintain optimism until the very end (Stuart Pendred); to the episodic roles of Melot (Ben Thapa), the Shepherd (Stephen Rooke), the Young Sailor (Edward Hughes) and the Steersman (Thomas Colwell).

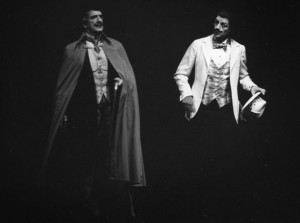

Photo: Matthew Williams Ellis

In this production, there were several moments of unearthly beauty. First of all, the finale of Act II, in which Frode Olsen – in collaboration with the phenomenal Kate Romano (bass clarinet) – brought us to our knees with the heartbreaking monologue of King Marke, the drama’s most tragic character, a dignified ruler who (unlike the two protagonists) does not manage to come over to the other side and experience ‘the thing in itself’ – a lament sung with surpassing beauty, in an old, breaking voice, but for all that with improbable power of expression. Secondly, the ideal blending of the lovers in the passage from the earlier love duet when Isolde and Tristan sang ‘Wonne-hehrstes Weben, liebe-heiligstes Leben’ as a single being overcome by ecstasy, almost inaudibly opening the phrase just a little bit, opening it up wide, and then closing it without slamming the door. Thirdly, ‘Muss ich dich so versteh’n’ in Tristan’s death scene, which would move an entire avalanche of stones to tears. And finally, the Liebestod, after which ensued a deathly silence, preceding a veritable storm of applause. Enough to remember this production for the rest of one’s life.

Though British critics – spoilt by productions at the Royal Opera House and on the country’s other leading stages – grumbled about the staging, everyone was agreed in their enchantment with the musical side of the Longborough Tristan. Jessica Duchen, who a month before the première expressed herself concerning the Longborough enthusiasts in a quite protectionist tone, was later not able to find words to express her admiration. It will suffice to mention that Duchen is going to the July production in Bayreuth and has serious doubts whether the team under Thielemann’s baton, with Stephen Gould and Anja Kampe in the cast, will be able to achieve the level to which the modest musicians from a provincial opera house in Gloucestershire were able to rise. She supplied her passionate review for the Independent with the following long and characteristic title: Excuse me, but why isn’t this man conducting Wagner at Covent Garden and Bayreuth?

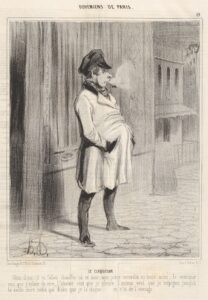

Photo: Matthew Williams Ellis

Indeed – why? Perhaps Peter Wedd – with whom I talked the next day – is right when he comments upon this strange situation with a quote from a quatrain by William Blake: ‘When Nations grow Old, the Arts grow Cold, and Commerce settles on every Tree’. Here in Poland, they froze solid already a long time ago. I myself know conductors whose knowledge and sensitivity continue to escape the notice of Polish opera house directors. Maybe it is time to go out to the country, look for some abandoned chicken farm and start over again from scratch?

Translated by: Karol Thornton-Remiszewski