Not So Merry Old England

Sacred vocal music developed during the Tudor era under the overwhelming influence of the Franco-Flemish School and the music of the Italian Renaissance. […] The English Baroque turned out to be a posthumous child of the beautiful but terrible era of the Tudors.

***

In 1485, the Wars of the Roses came to an end. In the Battle of Bosworth, King Richard III, the last of the Plantagenet kings, perished. The crown passed to Henry VII. A new chapter opened in the history of England: the Tudors would reign for almost one hundred and twenty years. That period would come to be idealised as ‘Merry Old England’ – an idyllic vision of pure Englishness, of a land of plenty, smelling of beer and Sunday roast with sage. Yet the wars left the kingdom in a lamentable state. The succession of armed clashes, beginning with the skirmish at St Albans thirty years before, had deprived it of its finest sons.

Fortunately, Henry VII – for all his ruthlessness – turned out to be one of the most effective rulers in English history. From the moment he took to the throne, he consistently pursued policies aimed not only at keeping the peace, but also at laying the foundations for future economic prosperity. He supported music, which became one of the crucial elements in the education of the nobility and the royal household. His son, Henry VIII, would be proficient on the lute, organ, flute and harp, and he composed and performed his own songs. His permanent royal chapel comprised mainly musicians brought from abroad: from Italy, France and the Netherlands. Henry’s example was followed by further Tudors: Philippe de Monte (1521–1603), born in Mechelen and educated in Italy, whose output was compared with the achievements of Orlando di Lasso, worked for many years at the court of Mary I.

William Byrd, Psalmes, Sonets, & songs of sadness and pietie (1588).

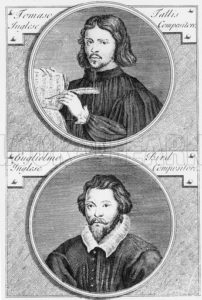

Sacred vocal music developed during the Tudor era under the overwhelming influence of the Franco-Flemish School and the music of the Italian Renaissance. Thomas Tallis (1505–1585), a veteran in the service of Henry VII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elisabeth I, who remained an ‘unreformed Roman Catholic’ to the end of his days, went down in the history books as the composer of the famous forty-part motet Spem in alium, written c.1570, which betrays influences from the Venetian School. Yet that same period gave us other masterpieces, in which Tallis deliberately referred to Flemish polyphony, subordinating melismata and counterpoint to the rhetoric of the text. In the motet O nata lux, rhythms, accents and scales merge. Harmonic dissonances appear on words that are key to salvation theology. Each work by Tallis became a musical debate on faith and the composer’s personal voice on the question of the English Reformation.

Tallis and his pupil William Byrd (1539–1623) enjoyed a monopoly on polyphonic music granted them by Elisabeth, along with a patent for printing and publishing sheet music. Tallis’s privilege covered the right to publish sacred works in any language. Byrd went several steps farther, assimilating the continental tradition in Masses and motets and forging a synthesis of the models that held sway on both sides of the Channel. He also remained faithful to Catholicism throughout his life, which may explain why his works, from the Eucharist hymn Ave verum Corpus to the lamentational Lulla Lullaby, tend to trigger associations with intimate prayer more than with public manifestations of faith.

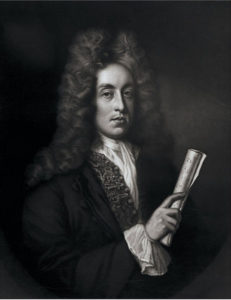

Henry Purcell by John Closterman (date unknown).

The fortunes and creative paths of their successors unfolded differently. The first wave of Reformation in England, preceded by Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, was of purely political foundations. The true reform came only with the rule of Edward. Mary’s attempt to restore Catholicism was followed by a violent turn of affairs under the reign of Elisabeth. The fate of the Catholics was determined by the outbreak of the war with Spain in 1588: from that moment on, they were seen as traitors. Opponents of the Anglican Church began to leave the island en masse.

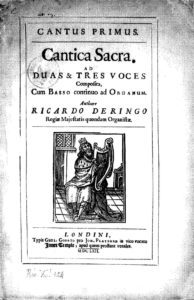

Peter Philips (1560–1628) began as a chorister at St Paul’s in London. At the age of twenty-two, following his ordination, he went into exile in Italy, via Flanders; he died in Brussels. Richard Dering (1580–1630), of the next generation, spent most of his life in the Spanish Netherlands. Significantly, both men wrote vocal music in the Italian style. Philips adhered to the more conservative models of the Venetian School, whilst Dering took up a creative dialogue with the mannerists, including Sigismond d’India, which with time earned him a reputation as one of the pioneers of the English Baroque.

That era was yet to come, delayed by three English civil wars and the reigns of the Cromwells. Its beginnings were tortuous: rejected by the courts, which were preoccupied by conflict, it was derailed by its distinctiveness in relation to the Continent. It finally emerged, during the Stuart restoration, simpler and more plebeian than in Italy and France, and at the same time fragile and beset by contradictory emotions, like the alarmed Mary, mother of Jesus, from The Blessed Virgin’s Expostulation by Henry Purcell (1659–1695), to words by Nahum Tate. The English Baroque turned out to be a posthumous child of the beautiful but terrible era of the Tudors. It only altered its appearance after the defeat of the Stuarts. But that is another story entirely.

Translated by: John Comber