The Saga of a Completely Different Siegfried

It is time to take the medieval epic poem The Song of the Nibelungs off the shelf, and put the libretto of Wagner’s Ring in among the other fairy tales. The protagonist of this tale, one of the bloodiest in the history of European literature, is the Germanic princess Kriemhild, who dreamed of a falcon killed by two eagles. Her mother explained to her daughter the meaning of the ominous dream, which augured the death of her future husband at the hands of assassins. The frightened princess decided to remain a virgin forever, but fate decided otherwise. Siegfried the valiant dragon-slayer arrived at the castle of the House of Burgundy and asked King Gunther for the hand of his virgin sister. The king agreed, on the condition that the warrior would help him win the affection of the beautiful Brünhild, Queen of Iceland. Siegfried impersonated Gunther and fulfilled the king’s wish. He himself married Kriemhild. The continuation of the epic poem is a long and convoluted story of betrayal, intrigue and corruption which leads first to the fulfillment of the prediction in Kriemhild’s dream, and then to bloody revenge of catastrophic effect on her husband’s murderers.

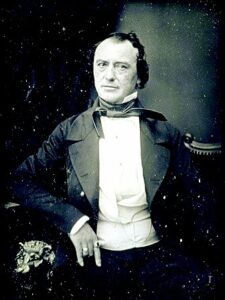

In the Icelandic Saga of the Völsungs, alluding to the earlier Poetic Edda, the dragon-slayer’s name is Sigurd; during one of his wanderings, he awakens Brynhild from an enchanted sleep and falls in love with her; she, however, foretells him death and marriage to another woman. In the background of all medieval tales of the fortunes of Siegfried/Sigurd are invasions of the Roman Empire by the Huns and Germans, as well as the slow formation process of the Frankish tribal state, on whose foundation the empire of Charlemagne arose over time. Interwoven with references to history is fairy-tale reality – tales of dragons, dwarves and werewolves, spells and love potions, invisibility helmets and shattered swords. This treasury was drawn upon by Wagner and by Friedrich Hebbel, the author of a stage trilogy entitled Die Nibelungen; in 1862, it was used by French dramaturg and librettist Alfred Blau, who was inspired by the French translation of the Edda from nearly a quarter century earlier, and by the quite fresh translation of The Song of the Nibelungs. It was at this time that the first sketches were made for the libretto of Sigurd, which another librettist and influential theatrical personality – Camille du Locle – put into versified form. The two librettists were friendly with Ernest Reyer, before whom the doors had just opened to a great career, as a result of his recent success with the three-act opera La statue, esteemed by Massenet himself and performed at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris nearly 60 times in its first season.

In the opinion of some musicologists, a draft of the score of Sigurd was ready even before the première of Wagner’s Das Rheingold, not to mention the staging of the entire tetralogy in Bayreuth five years later. So it is difficult to speak of a French ‘answer’ to Der Ring des Nibelungen, of which Reyer had an otherwise quite vague idea. He carried out the first negotiations with the Paris Opera already in 1866; later, he undertook further negotiations, rejected because of the work’s supposed ‘unperformability’, though at the beginning of the 1870s, the composer presented fragments of Acts I and III as part of the Concerts Populaires under the baton of Jules Pasdeloup. It is not out of the question that the Opera’s management was afraid of a disaster after the cool reception of Érostrate at Le Peletier in 1871. Finally, the world première of Sigurd took place at La Monnaie in 1884, and ended in enormous success. In the next season, the opera conquered stages in London, Lyon and Monte Carlo, after which it arrived in triumph – though in an abridged version – on the stage of the… Paris Opera. For many years, Sigurd drew crowds: Edgar Degas reportedly saw it no less than 37 times.

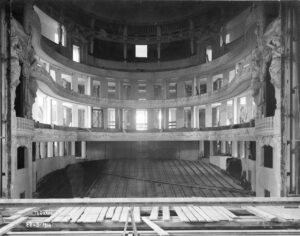

Nancy, 1914: the new stage under construction. Photo: opera-national-lorraine.fr

The Théâtre de la Comédie in Nancy, once located at the rear of the Musée des beaux-arts on the western frontage of the Place Stanislas, burnt to the ground on the night of 4–5 October 1906, after a rehearsal of Thomas’ Mignon. A decision to rebuild was made immediately after the fire. The competition for the design was won by local architect Joseph Hornecker. The building was erected on the eastern frontage, behind the surviving façade of the former bishop’s palace. The grand opening took place in October 1919 – the theatre’s operations were inaugurated with Reyer’s opera. A hundred years later, the Opéra national de Lorraine decided to open its jubilee year with two concert performances of Sigurd.

Not only the occasion, but also the place was appropriate to resurrect the memory of the four-act opera on motifs from The Song of the Nibelungs: the titular protagonist fell with a stroke from Gunther in the nearby Vosges Mountains, and a substantial portion of the plot plays out in Worms, just under 200 km away. It is all the more regrettable that they were not able to present the work in a fully-staged version, especially since Sigurd is in certain respects more dramaturgically concise than Wagner’s Ring, and abounds in episodes that just beg for the participation of an imaginative stage director. But it would not be right to complain, since the theatre’s management was able to engage a choice cast of soloists and, above all, a conductor who knew the material well.

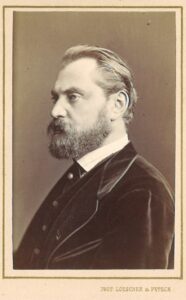

For Sigurd is a thoroughly French opera – with its rich orchestration and epic panache, the score reminds one of Berlioz’ Les Troyens; with its references to declamatory style and Classical division into scenes, with clearly-indicated participation of chorus and orchestra, it resembles Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride; and with its picturesque contrasts, it brings to mind the grands opéras of Meyerbeer. In addition, Reyer intended for the cast to include singers with voices of exceptional values: a truly heroic tenor, two full-blooded dramatic sopranos, a powerful baritone with a sonorous and open, almost tenor-like high register, several ‘French’ basses and a true contralto. The difficulty of putting this all together into a convincing whole rested on the shoulders of a conductor well acquainted with this idiom – in this case, Frédéric Chaslin, who had dealt with Sigurd before and whose interpretation of this work is impressive not only in its feel for pulse and tempo, but also for its logical handling of the narrative and, above all, ideal collaboration with the singers.

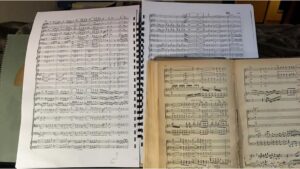

The dress rehearsal of Sigurd at the Opéra national de Lorraine. Photo: @frederic.chaslin FB Official Page

In the large title role bristling with difficulties, Peter Wedd – the only foreigner in a cast otherwise comprised only of Francophones – put forth an amazing performance. His ardent, slightly nasal tenor sounded a tad brighter than usual, but without any loss of richness in overtones. Only at moments could one get the impression that the singer was moving in a stylistic language foreign to him: for most of the narrative, as usual, he was impressive in his splendid messa di voce technique and sonorous squillo, with beautiful phrasing in the expansive monologues (superb ‘Le bruit des chants s’éteint dans la forêt immense’ in Act II) and sensitive music-making in the ensemble numbers. Decidedly ‘at home’ was Gunther in the person of Jean-Sébastien Bou – phenomenally balanced in all registers of his baryton-martin, flawless in intonation, very flexible and brilliant in clarity of articulation, supported – of course – by superb diction. Jérôme Boutillier displayed very good technique as well as vocal beauty, though with slightly less vocal culture – but then again, a certain dose of vulgarity is consistent with the repulsive character of Hagen. In the smaller male roles, Nicolas Cavallier (the High Priest of Odin), Eric Martin-Bonnet (the Bard) and Olivier Brunel (Rudiger) put in decent performances.

Two wonderful sopranos dueled in a manner completely befitting rivals for the love of the valiant Sigurd. Catherine Hunold (Brunehild) is enchanting, above all, in her extraordinary musicality and intelligent phrasing. Compared by French critics with Régine Crespin, she has a softer, warmer voice, not so dense in the middle register – at the concert in Nancy, it blossomed into its full brilliance only in Act IV and, to a certain extent in accordance with the narrative, eclipsed the voice of Camille Schnoor in the role of Hilda. The German-French singer’s strength flagged in the finale – a pity, because her velvety, dark soprano displays certain predispositions toward a dramatic voice; but for the moment, she is still closer to the aesthetic of Puccini’s operas. Marie-Ange Todorovitch came across quite convincingly in the role of Uta, though she did sometimes have to cover up vocal deficiencies with sincerity and wisdom of interpretation.

Separate words of praise are due to the enthusiastic chorus (rousing finale of Act III!) and the orchestra, alert and obedient to Chaslin’s baton, deftly highlighting all of the expressive and textural values of this extraordinary score. Ernest Reyer, by later musicologists patronizingly called ‘the Wagner of La Canebière’, had terrible luck. He composed perhaps not a masterpiece, but with all certainty a work that does not deserve a place in the operatic junk pile. Sometimes it is worthwhile to follow the activities of one’s competition, especially one gifted with such talent as the master of Bayreuth.

Translated by: Karol Thornton-Remiszewski