The Polish edition of The Handmaid’s Tale, translated by Zofia Uhrynowska-Hanasz, appeared in 1992, seven years after its original publication in Canada. Published by PIW as part of the Klub Interesującej Książki (Interesting Book Club) – a project intentionally less prestigious than the famous ‘black series’ of contemporary world literature – it gained a small band of enthusiasts, but generally failed to make any great ripples, like the earlier translations of three other Margaret Atwood novels. No interest was aroused in Poland by Volker Schlöndorff’s 1990 film adaptation either – possibly because it was not well received by the critics and was not released in Polish cinemas. Poland only enacted a new family planning law – considerably more restrictive than the law on the conditions for terminating pregnancy that had been in force since the mid-fifties – in 1993.

Atwood and her terrifying dystopia became a hot topic in 2016, when the first Black Protests swept Poland, after Ordo Iuris and the Pro Life Foundation announced that it was to set before parliament a citizen’s bill proposing a complete ban on abortion and the introduction of severe punishments for ‘prenatal murder’. In 2020, after the notorious verdict (questioned in legal circles) issued by the Constitutional Tribunal, we woke up on the threshold of the Republic of Gilead, with an abortion law stricter than in Iran or Pakistan, and the tightest in Europe, not counting the ultra-Catholic Malta, where abortion is absolutely forbidden. Legal abortion, theoretically possible in cases where the woman’s life is threatened or in situations where the pregnancy is the result of a proscribed act, in practice became a fiction.

In Poland, Atwood’s novel found favour, and female readers in particular were amazed that the Canadian writer had managed to foresee a future that in 1985 had seemed unimaginable. Yet The Handmaid’s Tale was actually reflecting, in a crooked mirror, the fears of women across the Atlantic. It was first published around the same time as Ronald Reagan introduced the so-called Mexico City Policy, which blocked the financing of all organisations concerned with reproductive health. The principle of a ‘global gag’ became a push-me-pull-you of American politicians: by turns abolished by the Democrats and restored by the Republicans, it reemerged, in a monstrous form, in 2017, under Donald Trump. The spectre of Gilead, temporarily dispelled in the United States by Biden, still hovers over Poland, a country where the cult of Reagan, fighting ‘for our freedom and yours’, is surprisingly persistent, and even the current governing coalition is riven by disputes over abortion – and that after the eight-year nightmare inflicted on many Poles, not just women, by the right-wing populists.

Avery Amereau (Serena Joy) and Kate Lindsey (Offred). Photo: Zoe Martin

That probably explains why I perceive Atwood’s book and all its adaptations as if through a pane of glass. That tale no longer shocks me. I see it rather as a reflection of a partially realised scenario, a possibly belated warning against a deluge of fundamentalist oppression around the world. That also applies to the opera by Danish composer Poul Ruders that was written in 1998 and premiered two years later at Det Kongelige Teater in Copenhagen, with a libretto by Paul Bentley translated into Danish. The English National Opera has been associated with this work almost from the start. The Copenhagen production, directed by Phyllida Lloyd, with sets by Peter McKintosh, reached the London stage in 2003, where it was first performed in English. The Handmaid’s Tale, after several productions in the United States and Australia, returned to the ENO in 2022, in a staging by director Annelise Miskimmon, the theatre’s artistic director, and her regular scenographic collaborator Annemarie Woods. In February 2024, the production was revived under the baton of the same Portuguese conductor, Joana Carneiro, and with the participation of several singers from the original cast.

Bentley and Ruders, choosing between the main heroine’s expansive inner monologue and a sort of hybrid in which Offred’s emotions, reflections and recollections clash with the fairly linear narration of events in Gilead, opted for the latter solution, remaining essentially faithful to Atwood’s text, but at the expense of the drama: almost to the end of the first act, the tale is rather static and heads laboriously towards the climactic scene of Janice’s labour (the child turns out to be disabled and is slain), while in the second act it hurtles along blindly, diverting the audience’s attention away from the next climax, in the scene of the public execution. The flaws in Bentley’s libretto are largely compensated for by Ruders’s highly expressive, at times even ruthless, music, which meanders between atonal and tonal, drawing liberally on a wide range of conventions: from Mozart, through Richard Strauss, Berg and Stravinsky, to the classics of American minimalism. Ruders also introduces elements of pastiche and grotesque into his score, although, unlike his beloved Penderecki, he does not use them as material for further compositional actions, employing them rather as quotations, musical symbols, motifs appearing out of nowhere, which vanish a moment later into a dense orchestral texture (recurring references to John Newton’s hymn ‘Amazing Grace’, the promise of the chorale ‘Ich bin’s ich sollte büssen’ from the first movement of Bach’s St Matthew Passion, dispersed into nothingness). Ruders’s imagination and excellent technique come to the fore especially in the remarkably colourful orchestral part. Things did not turn out so well with the solo parts: the only character whom the composer really allows to speak with a full voice is Offred. The other protagonists communicate in broken sentences, snatches of arioso, often exceeding the compass of any voice whatsoever, with the result that a not entirely comprehensible emotional barrier is created between the stage and the audience (I most regretted the character of Nick, who plays an extremely important, even crucial, role in Atwood’s narrative, but is overlooked by the production team).

Kate Lindsey. Photo: Zoe Martin

Miskimmon, herself brought up in a country of fanatism and religious prejudice, did not follow the lead of several of her earlier productions and resisted the temptation to transfer A Handmaid’s Tale to the realia of her native Ireland. Together with Woods, she created a pure, clear theatrical space, in which she placed characters and props triggering unequivocal associations with Atwood’s book and with the vision of the team behind the highly publicised series from 2017, anchored in the collective imagination. The handmaids wear dresses similar to the costumes of Amish women – in various shades of red, the intensity of which appears to suggest their ‘reproductive usefulness’ in Gilead (Offred has the ‘reddiest’ dress). The wives of the dignitaries, including Serena Joy, are dressed in blue, the regime’s functionaries in dun uniforms, and the privileged men parade around in black. The transitions between scenes are smooth, mostly thanks to the brilliant lighting (Paule Constable) and quick changes of props behind a red curtain that also serves as a screen for Offred’s black-and-white recollections (projected by Akhila Krishnan). Miskimmon retained several forceful gestures from the original, including the ritual of inseminating a handmaid in the arms of the lawful wife of the ‘reproductor’, while others are softened (to marvellous effect), replacing the corpses hanging on the wall with photographs of the condemned, while transferring the actual execution to the domain of theatrical symbol (one can infer the function of the rope that disappears somewhere between the wings and the flies solely from the precise directing of this image). At several points, she succeeded in relieving the mood of ubiquitous menace with a touch of black humour (the handmaids use prayer machines, modelled on one-arm bandits). The sole mistake in the staging – a major error, alas – is turning the spoken male role of Professor Pieixoto into a performance by an actress (the excellent Juliet Stevenson). After all, it is precisely Pieixoto who binds the narrative together with a tragic clasp, admitting at an academic conference in 2195 that as a man he does not have the right research tools to verify the handmaid’s tale – thereby indirectly testifying that women were erased from the history of the Republic of Gilead.

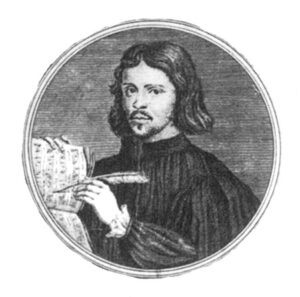

The main collective hero of the evening proved to be the orchestra – in magnificent form, sensitively reacting to the precise instructions from Joana Carneiro, who kept perfect command over proceedings. I was less taken by the chorus, which was lacking cohesion, which for me is extremely important in this work, where the objectified women ought to speak in the uniform voice of a nameless crowd. In the thankless supporting roles, most impressive was Avery Amereau (Serena Joy), whose dark, velvety mezzo-soprano, with a beautifully cultured, truly alto bottom register, aptly conveyed the sadness of the infertile wife – profound and despairing, like the biblical Rachel. Nadine Benjamin was convincing with her sonorous soprano and abundance of energy, ideal for the role of the rebellious Moira; the same goes for Scottish soprano Eleanor Dennis, who brought a great deal of freshness to the part of Ofglen, Offred’s friend. A class unto herself was Susan Bickley in the mezzo-soprano role of the main heroine’s mother. Rachel Nicholls gave a bravura performance of the soulless Aunt Lydia, to whom Ruders gave a part that is downright repulsive in vocal terms: full of screamed commands and broken, barking syllables in the top register. The male singers came across worse, including the booming bass James Creswell, who decidedly lacked subtlety in his interpretation of the emotionally unstable Commander Fred.

Kate Lindsey and Eleanor Dennis (Ofglen). Photo: Zoe Martin

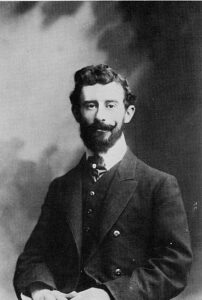

Yet everything was offset by the titular handmaid, defined with the derogatory, possessive nickname Offred, meaning ‘of Fred’. Her lost life, existential fear and continually crushed hope were marvellously rendered by the American mezzo-soprano Kate Lindsey, possessing a voice of great beauty, led to masterful effect and with great facility, particularly in the top scale, where the ethereal piano seems to reach us at times from another world, at times from the depths of an agonising yearning for happiness irrecoverably lost. I am not at all surprised that in the second act she was given a duet with herself (her younger incarnation is usually entrusted to another soloist): still ringing in my ears are her last words, ‘how can I keep on living?’, sung in unison, before a split on the last note into a piercing semitone interval. I think the opera would benefit from Ruders ‘slimming down’ the narrative and instead allowing Offred to enter into a closer relationship with one of the musically better drawn characters.

This revival almost came to nought. Until the eleventh hour, it was threatened by a strike of the ENO musicians, protesting against planned redundancies in the orchestra. The crisis has been averted for the time being, but a decision to force the ensemble to move to Manchester seems inevitable. Dark clouds are also gathering over the Welsh National Opera. I just hope that a hundred years from now no Professor Pieixoto will exclaim at another symposium that he has too little evidence to verify anonymous reports of the former splendour of operatic theatre in Great Britain.

Translated by: John Comber