On Saturday, 24 November, a four-part chamber cycle Life Without Christmas by Gia Kancheli will be performed on one long day, at times corresponding to the names of the individual „prayers” – as part of the Nostalgia Festival in Poznań. Below, you can read my essay, reposted by kind permission of the Festival (http://www.nostalgiafestival.pl/en/news/o-potrzebie-jakichkolwiek-swiatbrdorota-kozinska-2).

***

What would life without Christmas be like? According to Christian theologians, it would be a gloomy existence, stripped of the hope for the coming of the Saviour who would wipe away the tears of sinners and show them the way to the Kingdom of Heaven. It would be a life in the constant turmoil of war, for if Christ would not be born, there would be no death on the cross, and thus no exoneration of humanity through faith and reconciliation with God. The darkness of a life without Christmas would not be brightened by any good news: neither the joyful news of sins being forgiven, nor even the consolation that someone would help us bear them beforehand.

What would such a world be from the point of view of children or the less attentive adults of simple faith? A world without gifts? Perhaps there would be another opportunity to give them. But what would the attraction be if our homes would never smell of Christmas trees, and in our kitchens, there would be no aroma of ripe gingerbread browned in the oven. Without Christmas, we would not be able to dream, even in our adult years, to at least once see the mechanical nativity scene at the Franciscan Fathers’ Church at Bernardyński Square in Poznań. There would be no point in hanging mistletoe over the Christmas table. We would not call our forgotten relatives and friends once a year. We would not leave an additional place setting for the stray wanderer. We would forget that people should never be alone.

Photo: Isabelle Francaix

Giya Kancheli grew up in a country where real Christmas no longer existed. Contrary to popular opinion, the Soviet authorities did not introduce an official ban on the winter festivities but made every effort to appropriate the earlier tradition. In the 1920s, still with the best-intended desire to fight superstition in mind, outstanding avant-garde artists joined the campaign. A few years before the onset of the great terror, members of the League of the Militant Godless went into action as one of the most effective Bolshevik instruments for fighting religion and religious organisations. Special patrols followed fellow citizens and reported on discovered instances of holding home-based sochelniks (Christmas Eve suppers). The activists demanded that the guilty be punished for these ‘embarrassing situations.’ Churches, both Orthodox and of other denominations, were closed down and used to accommodate the infamous museums of atheism. Objects of worship were destroyed. True repressions began after the liquidation of the New Economic Policy and the replacement of this hybrid doctrine with a command-and-distribution system. Combating the Church’s influence was supposed to facilitate the fight against peasants. The celebrators went underground.

The one to bring them back to the surface was Stalin, who commanded the celebration of a secular New Year. In 1935, the same year in which Giya Kancheli was born, he surrounded Moscow’s Manezhnaya Square and the Kremlin courtyard with Christmas trees. The victims of the propaganda machine were mainly children, showered with cheap gifts delivered to the most remote places in the USSR by the same activists as before, and fed with stories of kolkhoz farmers, brave heroes of the civil war and udarniks (shock workers). The victims of the coercive apparatus were mainly adults, among them prisoners of Stalinist gulags, who had to celebrate this terrible Non-Christmas to a strictly defined scenario under the knout of the communist party propaganda department.

Kancheli remembers that his mother and grandmother secretly took him to church primarily to drag the boy away from his passion for playing football. It helped in so far as little Giya never became a real militant atheist. Since then, he has been entering the space of the sacrum: in churches, mosques and synagogues, to enjoy the absence of worshipers, the faith-charged silence, and the emptiness, which, in his opinion, hold more prayers than a temple filled to the brim during a service.

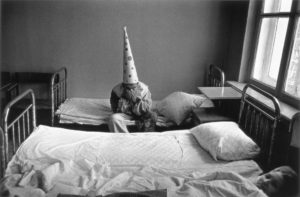

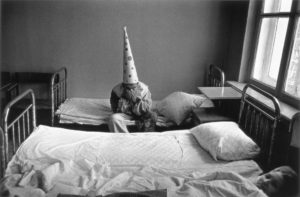

New Year’s Eve in the Kashchenko Psychiatric Hospital in Moscow. Photo by Pavel Krivtsov (1988)

It was not until the glasnost policy and Gorbachev’s reforms that Western musicologists started to seek hidden meanings in the works of Soviet composers, to track signs of writing between the lines, giving a voice to others or hiding in the shadow of suppressed religion. The time arrived for a redefinition of the legacy of Shostakovich, whose brassy overtones turned out to be only the tip of an iceberg of emotions and never externalised yearnings immersed in the depths of an icy ocean. The time arrived to decipher the painful symbols contained in the music of Arvo Pärt, Sofia Gubaidulina and Vyacheslav Artiomov. People and their tragedies began to emerge from the mysterious clusters of sounds. A cry arose from the depths of Kancheli’s symphonies and operas, from his theatre and film music, voicing mourning, fear and solitude, a regret for what had been lost, his nonacceptance of violence and a simple childlike innocence.

Kancheli emigrated from Georgia in 1991, shortly after the election of President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, overthrown on 22 December by the coup of the paramilitary organisation Mkhedrioni, most likely linked to the Russian secret service. He moved to Berlin as a beneficiary of a grant from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD), the German Centre for Academic Exchange, financed mainly from public funds of the Federal Republic of Germany. Four years later, he became a composer-in-residence for the Royal Flemish Philharmonic in Antwerp and settled permanently in Belgium. During the transitional period, even before leaving his homeland, he began composing the cycle Life without Christmas, consisting of four ‘prayers’ for the subsequent times of day: morning, daytime, evening and night-time. If these are prayers, they are so in a very broad, extra-liturgical sense. Within them, Kancheli does not refer directly to any religion, but calls for a spirituality that searches, does not submit to any creed, and wakes up at night with a scream, ‘Where is God (if He exists at all)?’ It is music echoing with the voices of angels that had never been heard. It is a song of innocence in an uneven struggle against aggression, violence and evil.

One can laugh at the repetitive structures, their shameless tonality and allegedly banal melodic phrases, until the listener realises that these are all prayers for a lost Georgia and, in a less obvious way, for a lost Soviet Union: for friends and colleagues escorted to the other bank of the Styx, for Avet Terterian, who is still unappreciated in the West, and for Alfred Schnittke, who is still not fully understood in Europe. For a multitude of composers who were banished, killed, stripped of their identity and condemned to a silence from which they can only be brought to the light by the cry: ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ It is the musical prayer of the righteous person who is suffering. The listener must now decide individually whether suffering is a punishment for sins and proof of the superior being’s disfavour, or proof that someone, without really knowing who it is, is always next to us, even when hope has died.

What would life be without any festivities? What purpose do festivals actually serve? To celebrate something or, perhaps, to partake in some fine entertainment? Where does the need to hold cultural festivities come from? Is it just about strengthening our sense of community, and if so, what kind of community? An aesthetic or national one or, possibly, one that is rooted in a wider geographical context? One that is connected by the same model of sensitivity, a similar worldview, blood ties or a collective subconsciousness?

New Year celebration in the Tbilisi Palace of Sports. Photo: ITAR-TASS

Regardless of the reasons, festivals are associated with a kind of religious experience, even by agnostics and atheists. They have their own rite and order. They recur at the same times, like the first snow, the vernal equinox or the moment when the leaves on trees start turning yellow, as if they were marking a symbolic turning point, a time when a cycle concludes to be reborn soon afterwards. During a harvest of festivals, a sacrifice must be made to the deities: those of theatre, music or literature. And then we must dive into a whirlpool of intense experiences, to listen, watch and read up a stock to last until the time before the next harvest, to help survive the time of sowing and give us strength to gather fertile crops, for which we will give thanks again the following year. In the same temple, guided by equally dignified priests, together with an ever-increasing number of artistic followers.

It all sounds anachronistic, because the world is developing. A loud street party took place a few hundred meters from my home. I tried to separate myself from it in the comfort of my studio with windows facing the courtyard, but it attacked me unexpectedly with posts on one of the social media sites. The noise coming from the neighbourhood created a jarring sonic background for dozens of images on Instagram, photos taken using selfie sticks and videos shot with mobile phones. This made me all too aware that even if I cut myself off from the community, it will still sweep me into the arms of virtual friends. Could it be that the new technologies, and the subsequent growing pace of life, as well as the need for increasingly more powerful experiences, will soon transform our existence into a continuous, all-embracing festival where there is no longer any room for reflection or giving thanks?

The actual word ‘festival’ has a relatively short history and appeared in English only in the late 16th century, borrowed from Old French where the adjective ‘festival’ referred to something joyous, closely related to the atmosphere of a major church holiday. But the predecessor of this form of art worship can be traced back to ancient Greece. In Delphi, a tribute was paid to Apollo during the Panhellenic Pythian Games, held since 582 BC in late August and early September, in the middle of the Olympic cycle, namely in the third year of the Olympiad. The tradition, however, goes even deeper to the rituals in honour of Apollo, organised every eight years and accompanied by the famous musical agons: competitions for the most accurate interpretation of a paean with the accompaniment of the kithara. Unlike the Olympic Games, the Pythian Games were, first and foremost, an arena for musicians and actors. With time, the set of competitions was extended with aulete contests, singing tournaments, and solo performances of kitharodes, as well drama, poetry and painting contests, to which the chariot races and wrestler battles provided only a picturesque backdrop. The winners were rewarded with wreaths of bay laurel branches, the holy tree of Apollo gathered in the Thessalian Tempe Valley.

Echoes of the ancient agons resounded later in medieval singing tournaments and were brought back to life in the collective European imagination by works such as Wagner’s Tannhäuser. From knightly manors, the contests gradually moved down the social ladder, turning into specific ‘tests of bravery’ for musicians belonging to specific communities. These were competitions where the participants could hope not only for the evaluation of their skills, but also for advice from the true masters of their respective professions and the spontaneous applause of the listeners gathered at the tournaments. The competitive element became secondary to the exuberant need to participate in a joyful musical celebration that fulfilled the role of some kind of catharsis and was also an integrative and educational event.

Are we taking part in joyous or, perhaps, a painful festivity? After all, the Nostalgia Festival is a celebration of musical memory: a thin albeit strong thread connecting us with what comes back to us, even though sometimes we would prefer to forget it. But we should not forget. I have just remembered that in the 1970s, my father was a guest at the Georgian Rustaveli National Theatre in Tbilisi, where Giya Kancheli was the music director. The guests from Poland were given a truly Georgian reception. Toasts were raised until dawn. The wives went to bed earlier. In the morning, my mother entered the bathroom to find the bathtub full of red roses. An apology for the drunkenness of the night before. An apology for a world where the lack of Christmas had to be offset with an attempt to provide some other festivity. A festivity which found its musical equivalent only after the death of the Soviet Union. The hated, enforced homeland of many great composers whose oeuvre we must – and should – discover many years after the fall of the ominous empire.

Translated by: Marta Walkowiak