Open the Door Before Music

The life of Bishop Martin of Tours was complicated enough even without the lofty embellishments of later hagiographers. A saint of the “undivided Church”, venerated by the Catholics, the Orthodox and the Anglicans alike, one of the first Confessors – witnesses of faith who somehow managed to die a natural death – Martin is also regarded as a pioneer of pacifist movements and modern humanitarianism. Contrary to Sulpicius Severus’ testimony, he did not run away from home to dedicate himself to God, nor was he forcibly dissuaded from baptism by his brute of a father or forcibly conscripted into the army.

The son of a Pannonian tribune seems to have simply missed the family calling. When he was a child, he moved with his family to Ticinum in Cisalpine Gaul – after his father had been granted veteran status as a reward for his faithful service, and with it numerous privileges as well as a large plot of land for cultivation. Indeed, Martin failed to meet the expectations of his progenitor, who named him after the Roman god of war for a reason. Not eager to fight, the ten-year-old Martin joined the ranks of the local catechumens, but was not baptised – not only out of fear of his parents, but also because the local bishop did not want to fall foul of the retired tribune and believed that one had to be mature enough in order to be initiated into Christianity. Martin became a legionary anyway, aware that as the son of a former cohort commander he did not have any other choice. According to some contemporary historians, he served in the army much longer than Sulpicius Severus claims, perhaps even as long as twenty-five years. Yet he did not turn out to be particularly good in this trade. On the eve of a battle against the Teutons, he tried to have his incentive bonus in the form of double pay exchanged for a discharge from the army. Arrested for cowardice, he faced serious consequences. He behaved like a true conscientious objector: he volunteered to go into battle at the front of the troops, defending himself only with the sign of the cross. But then a miracle happened: the enemy asked for peace.

Saint Martin dividing his cloak with a beggar. XIVth century wall painting from Skibby church, Denmark

Irrespective of whether Martin left the army as a youngster or a mature man, he was baptised shortly before returning to civilian life. He became an icon of charity thanks to a deed that ultimately determined his decision to become a Christian: when he encountered a half-naked beggar on his way to the city of Ambianum and was unable to give him alms, he cut his officer’s cloak in two and shared it with the beggar. His later life is the story of an unusual bishop of Caesarodunum (today’s Tours) who renounced the benefits of the his position in favour of living an ascetic life, preaching the faith “in the field” and ruthlessly fighting paganism. He zealously destroyed pagan idols and sacred groves, but forgave humans and took their sins upon himself. He died in missionary glory, away from his diocese. His body was ferried in secret on the rivers Vienne and Loire. A ceremonious funeral took place on 11 November 397 in Tours.

The day is celebrated as the Fest of Martin the Bishop. Strangely enough, it was on 11 November that the armistice between the Entente and the German Empire was signed in a railway carriage near Compiègne, France, ending the black night of the First World War. Even more strangely, in the early months of the conflict the London parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields was entrusted to the pacifist Dick Sheppard, who ran it like Saint Martin incarnate. Sheppard, too, had served in the army, but radically changed his views under the impact of his harrowing experiences during the Second Boer War. Shortly after the outbreak of the Great War, he volunteered, having become an Anglican pastor, to serve in a French field hospital, where he defended German soldiers from lynching by an angry mob several times. In 1915 he transformed his church into a centre providing help to all who needed it and called it the Church of the Ever Open Door. Every day he fed the homeless and put them up for the night there, cutting off any protests with one sentence: “You can’t expect to hear the truth on an empty stomach”. In 1924 he led the first ever religious service to be broadcast on the radio from St Martin-in-the-Fields. He would later boasts about letters from the faithful thanking him for the possibility of singing hymns in the company of their drinking mates in a nearby pub.

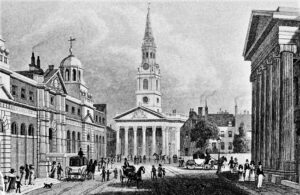

Perhaps it is the genius loci. Some years ago archaeologists discovered a burial ground beneath the church and a number of artefacts suggesting that a centre of Christian worship may have existed here already in Martin of Tours’ times – most probably built on the site of a sacred grove and demolished pagan altars. The first church of Saint Martin was built here in the thirteenth century – it was indeed located “in the fields”, outside the walls of London. Whether the monks of Westminster Abbey, who were in charge of the church, were guided by the teachings of the former legionary “who bought himself a place in heaven for a cloak” – is hard to say. We know that in 1542 Henry VIII had a new church built on the site: to nurse and bury the victims of a mysterious plague called English sweating sickness as far away from the Royal Palace of Whitehall as possible. As an additional precaution, he had a pillory erected in front of it – as a warning for the less sick – fearing the collapse of the parish healthcare system. The brick structure of the church proved so fragile that as early as in 1710 the Parliament decided to build a new edifice, allocating for the purpose a substantial sum of 22,000 pounds.

The design of the church was entrusted to the Scottish architect James Gibbs, a discreet Catholic who skilfully smuggled into his buildings elements of the “classicising” Carlo Fontana-style Baroque, while remaining an ardent follower of the Vitruvian triad of utility, durability and beauty. As the available space was limited, his original idea of constructing an edifice with a circular floor plan was rejected. Gibbs then decided to go the whole hog with the design and came up with a solution that embodied the idea of the “undivided Church”: a building without any religious symbols on the outside, with a Corinthian portico, a Baroque spire rising from the roof and a bright interior lit by windows with no stained glass. The construction works were completed in 1726. Initially, the building generated controversy, but soon became a model of Anglican church architecture, imitated countless of times throughout the Empire.

St. Martin-in-the-Fields church, engraving by H.W. Bond after a drawing by Thomas H. Shepherd, 1827

In addition to the charitable work that the parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields started with the local poor as early as in the eighteenth century, hiring adults to work in flax spinning and wool carding, and providing children with basic education in reading, writing and bookkeeping, the vicars of the church also made sure that services would have worthy musical settings. They hired the finest organists, beginning with John Weldon, a pupil of Henry Purcell and composer of incidental music to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, staged in 1712 at the Drury Lane Theatre. In the twentieth century – thanks in part to the collaboration with the BBC started by Sheppard – the church was also transformed into a thriving concert hall. In 1959 it became the home of the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, a chamber orchestra founded on the initiative of the violinist Neville Marriner, which played a key role in the British revival of historical performance of Baroque and Classical music. The Café in the Crypt has for years been welcoming jazz musicians. Less well-off music lovers can enjoy free afternoon concerts. In addition, the parish organises music education events, family events and the famous Concerts by Candlelight. Two months ago St Martin-in-the-Fields became the base of all of John Eliot Gardiner’s three ensembles: Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists and Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. The programme of the first evening at their new home featured Hector Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ.

Among this richness performances of Polish music have been sporadic and rather accidental. That is why Paweł Łukaszewski’s initiative to organise – in collaboration with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute – a festival of Polish sacred music, Joy and Devotion, at St Martin-in-the-Fields in November deserves special appreciation. Łukaszewski is an outstanding exponent of a strand of contemporary music appreciated much more in the United Kingdom than in Poland, where some critics remain sceptical about his oeuvre. Łukaszewski’s compositions fit perfectly with the British sensitivity to the sacred: perfectly constructed in terms of form, expertly exploring the possibilities and limitations of the human voice, they can appeal to the local audiences, from childhood accustomed as they are to choral music – the least expensive and most natural instrument of communal experience. The terms “anti-modernism” and “renewed tonality” do not bring to mind anything inappropriate to the Brits. The same categories of simplicity, subtle play with the past and purity of expression can be used to describe John Tavener’s oeuvre, the value of which no one questions in Poland. Maybe we are not detached enough, maybe we find “foreign” spirituality more palatable than our own, or maybe it takes truly phenomenal performers for music to speak to us fully.

Łukaszewski made sure such performers were in place and promises to attract them for the future editions of the new festival. As a composer he took a step back this time, adding just a few of his short pieces to the programme presented by the London Tenebrae Choir led by Nigel Short, a former member of the King’s Singers. The event also featured a concert by Echo, an ensemble active for four years and conducted by Sarah Latto, while the opening night featured the organist Rupert Jeffcoat and one of the UK’s most promising vocal ensembles, The Gesualdo Six – known to Polish music lovers as well – founded in 2014 by a young singer, conductor and composer, Owain Park. In addition to the oldest works of Polish vocal music, the programme of the entire event also included jewels of Polish Renaissance and Baroque, works by contemporary classics as well as pieces by representatives of the younger generation of composers, including Paweł Łukaszewski’s students.

The Gesualdo Six at St Martin-in-the-Fields. Photo: Marcin Urban

I went London to attend the inauguration – and to savour the incredible cohesion of the six quite distinct voices that make up The Gesualdo Six. Their singing is like a wise conversation, emphasising every rhetorical gesture, every rough and smooth texture, every mystery contained in the musical form. It finally revealed to me the phenomenon of Krzysztof Borek, the alleged maestro di cappella of the Cracow Rorantists. I hope that the living and the dead authors of the other compositions will forgive me: I only remember the Missa Mater Matris, a reworking of Josquin des Prés’ Missa Mater Patris – seemingly not far from the original, yet softer, more tender, full of strangely familiar harmonies. Perhaps this is what I had been missing in the few Polish performances of Borek’s works: a masterful familiarity with the style of the original and at the same time a fresh look at the work of a completely unknown composer. The ability to look into a score with the same attentiveness and emotion with which Martin – not yet a saint – once looked into the eyes of a frozen pauper on the road to Ambianum.

The Gesualdo Six shared with Borek everything they had. And they were none the worse for the experience. It is wonderful to be taught such a lesson in the church of Saint Martin in the Fields.

Translated by: Anna Kijak

Original article available at: https://www.tygodnikpowszechny.pl/swiety-marcin-wsrod-pol-169764