More And More Ifigenias

Following last year’s delight at Christoph Graupner’s Hamburg opera Dido, Königin von Carthago, my return to the Innsbrucker Festwochen der alten Musik seemed a foregone conclusion. This time, however, I plumped for the first of the festival’s three operatic premieres, and at the same time one of the two Ifigenias this year – the one at Aulis, composed by Antonio Caldara, after which, in the last days of August, festival-goers will be hearing Tommaso Traetta’s Ifigenia in Tauride, written almost half a century later. Again the choice was difficult, yet despite everything I had the sense that a good compromise had been reached. I made up for what I had missed last season and finally heard Accademia Bizantina in action in situ – the resident orchestra conducted by Ottavio Dantone, who in 2024 became music director of the Festwochen; knowing that I had to choose, I reluctantly gave up Traetta’s opera performed by Les Talents Lyriques with Christophe Rousset – to gain more interesting material for comparison with the triumph of their performance of Porpora’s Ifigenia in Aulide at the last Bayreuth Baroque festival.

This year’s Festwochen in Innsbruck, which are still on-going, carry the ambiguous subtitle ‘Wer hält die Fäden in der Hand?’, which conceals not just the suggestion of various strings being pulled in a diverse vision of the festival’s programme, but also an allusion to the production concept for Caldara’s work, which was prepared by the Catalonian puppet company PerPoc, under the direction of Anna Fernández and Santi Arnal, in their latest collaboration with the Russian illustrator and scenographer Alexandra Semenova, who has lived in Madrid for several years. Yet the initiative of reviving the forgotten Ifigenia in Aulide – more than three hundred years since its Viennese premiere – intrigued me, above all, on account of the libretto by Apostolo Zeno, the most important pre-Metastasio literary reformer of Italian opera seria, and the reverence with which Dantone approached the work’s musical material, deciding to stage it without any major cuts, in a version lasting almost four hours, with just a single intermission.

This is one of the earlier operatic takes on the myth (preceded by the Hamburg Die wunderbar errettete Iphigenia by Reinhard Keiser, from 1699, among others), and at the same time a work that contributed significantly to the later successes of these two Venetians at the court of Charles VI Habsburg: Zeno, making his debut in Vienna, and Caldara, who two years earlier had become court Vize-Kapellmeister, a post he would retain until his death, in 1736. It is not entirely true, however, that Zeno – when seeking a suitable lieto fine for a grand stage show to mark the emperor’s name-day in November 1718 – rejected Euripides’ original version and also a later version in which Iphigenia’s sacrifice was replaced by the sacrifice of a deer, after which he turned to Pausanias’ ‘third version’, where the heroine’s life is saved by the death of another Iphigenia, demasked at the last minute as the true object of the offering made to the gods.

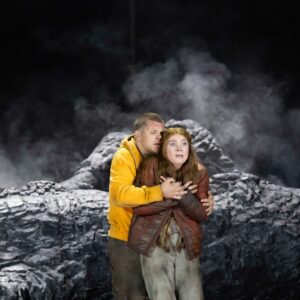

Ifigenia in Aulis. Carlo Vistoli (Achille), Shakèd Bar (Clitennestra), and Marie Lys (Ifigenia). Photo: Birgit Gufler

Zeno, of course, wanted to bring more amorous tension into the action, relinquishing Artemis’ intervention in favour of friction between two rivals – Ifigenia and Elisena – in their fight for Achille’s attentions. Yet he referred not to Pausanias, but to the tragedy by Racine, who moulded the variant related by Pausanias in his own image, creating an unprecedented version of the myth of the hero’s chosen one being saved by the noble suicide of another woman in love with him (in Racine’s play, her name is Eriphile). Pausanias does not suggest the existence of a second Iphigenia; he quotes a little-known myth from Argos, in which the only true Iphigenia was not a descendant of the Atreides, but a child born of Theseus’ rape of Helen, who gave her son to Clytemnestra to be raised.

Racine’s variant was taken up perhaps only by Zeno, a great enthusiast of the French tragedians, a poet who aspired to renewing the art of opera in the neoclassical spirit of the Accademia degli Arcadi. Caldara’s music, with its impressive clarity of texture, excellent contrapuntal work and hugely powerful expression, proved a splendid vehicle for the librettist’s intentions. Nevertheless, present-day reception of the Viennese Ifigenia in Aulide is hindered not just by its length, but also by its abundance of elaborate secco recitatives that add to the action, intertwined with a host of relatively short da capo arias that clearly head in the direction of Classical form.

All the greater is one’s admiration for the musicians who shouldered this complicated narrative and succeeded in maintaining the audience’s attention, despite the embarrassingly maladroit staging. At first, I thought that Semenova, PerPoc and choreographer Cesc Gelabert were attempting a humorous dialogue with Baroque theatrical conventions, but it soon came to light that they were treating their task with deadly seriousness. Given that this show was played in the Grosse Komödiensaal at the Hofburg in Vienna before the court of Charles VI, in spectacular chiaroscuro sets by Francesco Galli Bibiena that astonished viewers with the depth of their perspective, Semenova’s stage design created at times a grotesque impression. One-dimensional, static, overloaded with a host of ineptly replicated ‘Greek’ ornaments, floral and animal symbols, it failed to correspond to the action of the opera and took space away from the soloists. As if that were not enough, into this chaos, the stage team introduced dancers waving standards and cardboard panels, as well as animators of life-size puppets, which – for some unknown reason – doubled solely the female characters in the drama. And those puppets did not discharge any clear dramaturgical function; they were often passed by the puppeteers into the hands of the female singers, who, instead of concentrating on performing their parts, had to devote themselves also to animating their puppet counterparts.

Amid this accumulation of unnecessary props and tawdry costumes (the ladies in pseudo-ancient flowing robes, the puppets in outfits like something out of a folk pageant, the gentlemen in shorts and sandals, motley garments resembling the sheepskin cloaks worn by Balkan shepherds, and Corinthian helmets adorned with Baroque plumes, inexplicably set vertically on top of their heads), one would seek in vain for any psychological truth or relations between the characters. And yet that is what the libretto demands from the start, in order to understand Zeno’s unusual concept, borrowed from Racine, and assess for oneself whether Elisena is merely an obstacle on Ifigenia’s path to romantic fulfilment or perhaps a tragic figure; in order to grasp that the lieto fine in which one person gives up their life for another brings a portent of another catastrophe, namely, the death of Achille, who will never be united with his miraculously saved beloved.

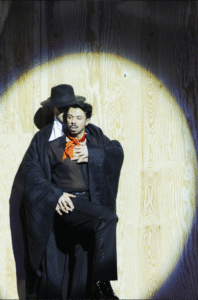

Filippo Mineccia (Teucro) and Martin Vanberg (Agamemnone). Photo: Birgit Gufler

These quandaries and dilemmas had to be considered solely on the basis of Caldara’s music – happily performed by forces worthy of the stars of the imperial court who at the premiere in 1718 helped the composer to take off his career in Vienna. The legacy of Maria Landini, the first performer of the part of Ifigenia, was taken up by Marie Lys, winner of the Cesti Competition in 2018 – a soprano blessed with a remarkably clear, distinctive voice, grounded on excellent technique, as she immediately demonstrated in the aria ‘La Vittoria segue, o Carlo’, moved to the beginning of the opera and sung in front of the curtain (this aria was originally something of a musical tribute to Emperor Charles VI, at the end of the grand spectacle). Lys coped even with a brief drop in form during Act II, effectively bolstering the interpretation of her character with excellent acting. The bright, crystal-clear and highly mobile soprano of Neima Fischer – a winner of the Cesti Competition from two years ago – enabled her to trace a convincing profile of Elisena, at times stubborn and naive, at times arousing genuine sympathy for her unrequited love for Achille. The mezzo-soprano role of Clitennestra was splendidly performed by Shakèd Bar, a singer with a live-wire voice, marvellous stage presence and phenomenal vocal technique, whose teachers included Sonia Prina.

Among the performers of the male roles, the greatest responsibility fell upon Carlo Vistoli, making his debut at the Innsbruck festival. Vistoli, nota bene also a pupil of Prina, is already a very experienced singer, including in Caldara’s music, as he fully displayed in the fiendishly difficult part of Achille, realised with a technically impeccable, strong countertenor voice, beautifully rounded and perfectly developed in the upper reaches of the scale. In some respects, however, he had the show stolen from him by Laurence Kilsby – in the much shorter, but bravura role of Ulisse. This young English tenor boasts not just an exquisite voice, excellently set and sparkling with an array of colours, but also the rare skill of ‘speaking in song’, which immediately arrests the audience’s attention. Excellent performances were given in the less prominent roles of Teucro, in love with Elisena, and Arcade, Agamemnone’s confidant, by two other finalists and prize-winners of the Cesti Competition: respectively Filippo Mineccia (countertenor) and Giacomo Nanni (baritone). Only Agamemnone was a tad disappointing in the interpretation of Martin Vanberg, endowed with a beautiful and well-directed tenor voice, who failed to fully identify with the character he was creating.

Dantone conducted with great sensitivity and imagination, not for a moment losing the pulse in a work that displays a relative lack of variety in terms of musical construction. The Accademia Bizantina, after a few minor slips in the prologue, immediately pulled itself together and played cleanly until the end, with incredible energy and a respect for the nuances of the score. A separate mention is due to the excellent continuo group in the countless secco recitatives.

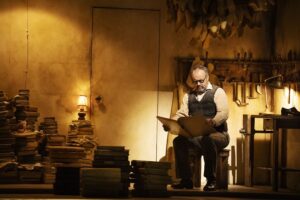

Žiga Čopi. Photo: Amir Kaufmann

I would not hazard the assertion that the misguided staging has buried the chances of successfully reviving Caldara’s forgotten opera. Yet a sense of dissatisfaction remained, enhanced the next day by the excellent impression made by the Sunday morning rehearsal of the Accademia Bizantina before the Scarlatti! concert at the Haus der Musik. In Dantone’s hands, in fragments of works by Alessandro Scarlatti – especially in the buffa scene from his Neapolitan opera L’Emireno – there was more theatre than in the whole stage concept of Ifigenia. It is worth emphasising all the more that Dantone is highly adept at working with young singers. And those singers learn very quickly, including the Slovenian Žiga Čopi, distinguished by a great vis comica and a soft, beautifully-hued tenor, which may soon develop into the truest haute-contre or Italian tenore contraltino.

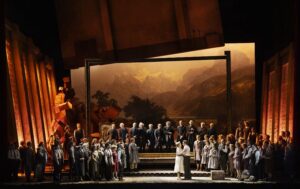

Ensemble Explorations. Photo: Mona Wibmer

I gained further evidence that music in itself is theatre that very same evening, at a concert in the Spanish Hall of Ambras Castle, where the Belgian cellist Roel Dieltiens – together with the members of Ensemble Explorations, reactivated following the pandemic – presented selected works from Bach’s The Art of Fugue. In a different order than usual. In the most disparate forces, from two to six instruments, but chosen from a wider range (violin, viola, cello, piccolo cello, recorders, oboe, oboe da caccia, positive organ, double bass, violone). And in an intellectual focus that conveyed all the more powerfully the complexity of human emotions. Those who had considered Die Kunst der Fuge to be a purely speculative work left the concert disappointed. Others, myself included, were reinforced in the conviction that interpretation does not preclude faithfulness to the composer, as long as it does not turn into an obsessive search for oneself in works created by someone else – as Edward Said once aptly put it.

From those two Sunday lessons in Innsbruck, I learned something else of value: that good music always holds its own against bad theatre. We will hear Caldara’s Ifigenia again one day. And there will be more Ifigenias. There is still so much to be discovered.

Translated by: John Comber