Dream of the Tempest

What do famous stock market investors and investment fund managers do when they retire? Warren Buffett, who will soon turn 94, apparently still enjoys playing the ukulele. Anthony Bolton, twenty years his junior, one of the UK’s most successful investors, retired from big capital management in 2014 and decided to complete his first opera. The premiere of The Life and Death of Alexander Litvinenko took place in 2021 at Grange Park Opera and received a rather mixed reviews from the critics, although even the fussy reviewers had to admit that the work was by no means inferior to most new British operas. Bolton’s composition received considerable publicity abroad, including in Russia, where Andrei Lugovoy, a deputy to the State Duma and the main suspect in the murder of the former KGB lieutenant-colonel, declared that the opera was the work of Western secret services, and thought that its premiere was a blatant provocation.

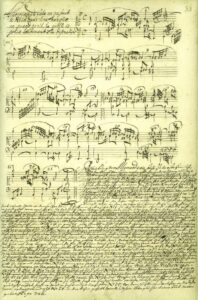

I did not make it to that performance due to pandemic-related travel restrictions. And I was really sorry I couldn’t make it, because Anthony Bolton, a graduate of the elite Stowe School and the famous Holy Trinity College Cambridge, studied music more diligently than many a professional composer in Poland. He played the cello and the piano, and his first composition teacher – while he was still at college – was Nicholas Maw, who later composed the opera Sophie’s Choice, based on William Styron’s novel and staged at the ROH in 2002 with Simon Rattle conducting. That same year Bolton returned to his old passion and began taking private lessons, for example with Colin Matthews, the same man who, together with his brother David, collaborated with Deryck Cooke on the reconstruction of Mahler’s Symphony No. 10.

Hugh Cutting (Ariel). Photo: Marc Brenner

This year brought another opportunity to check Bolton’s credentials. I realised that a visit to Grange Park Opera to attend the premiere of his second stage work, Island of Dreams, based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, required that I extend my stay in England by just two days. I decided to use this opportunity to catch up.

Malcontents once again complained that there was no point in attempting to create yet another adaptation of Shakespeare’s masterpiece given that Adès’ The Tempest already existed. Besides, in their opinion, one of the Stratford master’s last plays is not particularly suitable for operatic treatment, which should explain composers’ limited interest in this source of inspiration. This is not entirely true: The Tempest was hugely popular among opera composers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. In addition, unlike Adès, Bolton compiled the libretto from excerpts from Shakespeare’s original text, just as the Swiss composer Frank Martin did in 1956, taking Schlegel and Tieck’s classic German translation as the basis for the libretto of his opera Der Sturm.

Brett Polegato (Prospero). Photo: Marc Brenner

A lot suggests that Bolton can afford to engage in experiments, even unsuccessful ones. The cast of his Island of Dreams included Hugh Cutting in the countertenor role of Ariel. Prospero was originally to have been played by Simon Keenlyside, who was eventually replaced by the Canadian baritone Brett Polegato. The opera was directed by David Pountney in collaboration with the Austrian video artist David Haneke, with whom Pountney had tried out the innovative “triptychon” system – consisting of three precisely synchronised sliding projection screens – at the San Francisco Opera a few years earlier.

Musically, I got more or less what I had expected: a technically well-written and accessible opera, clearly inspired in its instrumental layer by the oeuvres of Holst and Britten, at times perhaps taking too sharp a turn towards the soundtrack of a non-existent film (multiple references to traditional English songs and Juventin Rosas’ nineteenth-century Mexican waltz Sobre las olas), though colourfully orchestrated with a great deal of imagination. Bolton fared a bit less well in dealing with vocal parts, giving ample opportunity to shine only to Prospero – in this case in a fine and wise portrayal by Polegato, a singer who possesses a seductive baritone with a beautiful timbre. The duets of the soprano Miranda (Ffion Edwards) and the tenor Ferdinand (Luis Gomes) lacked the passion of real emotion, though this was no fault of the performers, who sang with fresh, well-placed voices and made every effort to breathe some life into their cardboard characters. It is also a pity that the production failed to fully utilise the capabilities of Cutting, whose handsome and technically superb countertenor seems to be the dream voice for “Ariel’s music”, once so accurately contrasted by Jan Kott with “Caliban’s music”. The most memorable of the former for me was the wonderfully sensual song “Where the bee sucks, there suck I”. The latter was performed with great dedication by Andreas Jankowitsch, but his bass-baritone was not very resonant. Of the other soloists I was particularly struck by the baritone William Dazeley as Alonso, impressive because of not only his cultured singing, but also his excellent diction. I feel sorry the most for the overacted roles of Trinculo and Stefano (the tenor Adrian Thompson and the baritone Richard Suart). Compliments are due to the conductor George Jackson for his diligence and precision in preparing the whole thing with the Gascoigne Orchestra. As for Pountney’s concept – wherever any directorial work was in evidence, the overwhelming impression was that of a rehash of several dozen of Sir David’s past productions (an impression compounded by the costumes designed by April Dalton). As for the very colourful projections – I’m not sure that, if I were in Haneke’s place, I would let my name be associated with such an obvious AI work.

Brett Polegato and Ffion Edwards (Miranda). Photo: Marc Brenner

Despite all the reservations, I left the theatre satisfied. In England not every new opera has to be a masterpiece. Sometimes it can be the equivalent of a competently written easy read or a slick but unmemorable film adaptation of a classic. After all, there are sounds that give delight and hurt not.

Translated by: Anna Kijak