Veterans of the Polish period instrument performance wax emotional about Innsbruck. In the turbulent 1990s, when they came to the Tyrolean capital – full of hope and poor as church mice – to study with the greatest masters, they would sometimes slip in without a ticket to concerts at the Hofburg, the Spanish Hall of the Ambras Castle or St. James’ Cathedral. Since then dozens of early music festivals have sprouted up across Europe. The dreamers of those days no longer have a sense of being excluded. The time of legends and pioneers is no more: the oeuvre of past eras has escaped its niche and entered the mainstream. The odds have evened out, but, on the other hand, the public’s expectations have changed. In order be able to face up to the growing competition, artists must reassure the listeners that the existing formula is working or must reinvent themselves.

The godparents of the Innsbrucker Festwochen der Alten Musik were two enthusiasts: the bassoonist Otto Ulf, a teacher at the local secondary school, and the poet and translator Lilly von Sauter, who in 1962 became the curator of Archduke Ferdinand II’s impressive collection at the Ambras Castle. The following year the two organised the first castle concert – on the 600th anniversary of the handover of Tyrol to the Habsburgs. The idea caught on. Since then the Ambraser Schlosskonzerte have attracted a growing number of music lovers and curious tourists. In 1972 the Summer Academy of Early Music was launched thanks to Ulf’s efforts. The first “real” festival, under the artistic direction of its founder, was held in 1976. It was Ulf who shaped the Festwochen’s profile, which was unusual for the time and which elevated the event to the rank one of the most important festivals in Europe. Since the 1977 staging of Handel’s Acis and Galatea the programmes of successive Festwochen have featured stagings and semi-staged performances of old, often forgotten operas and oratorios. We can safely venture to say that Innsbruck is the cradle of the modern revival of Baroque opera.

The most fruitful years of the festival were those during the directorship of Ulf and his successor Howard Arman. The Festwochen became a breeding ground for new talent, a stepping stone in the great careers of future masters of historically informed performance, a model for the founders of new festivals and an encouragement to include early music in the programmes of other prestigious events. Something started to go wrong during the reign of René Jacobs, who treated Innsbruck somewhat dispassionately, as a sideline to his international activity, which was developing more dynamically outside Austria. The crisis worsened during the tenure of Alessandro De Marchi, an alumnus of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis and one-time assistant to Jacobs, who failed to revive the festival’s tried-and-tested but a bit outdated formula. De Marchi undoubtedly deserves praise for inaugurating the Cesti-Wettbewerb, a competition in honour of the Italian composer Pietro Antonio Cesti, who served for some time as the Kapellmeister at the court of Archduke Ferdinand Charles in Innsbruck. Prizewinners from previous years, including Emöke Baráth, Rupert Charlesworth, Sreten Manojlović and the Polish mezzo-soprano Natalia Kawałek, are developing beautifully, building careers not only in the Baroque repertoire. However, sceptics grumbled that De Marchi was making misguided programming choices and put his own ambitions above the patience of listeners, who were treated to hours-long performances of not always interesting rarities. The critics also raised concerns about De Marchi’s striking but increasingly mannered interpretations.

Graupner’s Dido. Jone Martínez as Menalippe and Andreas Wolf (Hiarbas). Photo: Birgit Gufler

One thing is certain: the festival began to lose the interest of audiences and foreign critics. It was time for reforms. The change of the guard in 2023, after the last season programmed by De Marchi, brought with it a change in the structure of the entire Festwochen management. Markus Lutz, the previous Managing Director, became Executive Commercial Director; Eva-Maria Sens was appointed Artistic Director; while the harpsichordist, conductor and researcher Ottavio Dantone, well-known to Polish audiences as well, was made the new Musical Director.

The motto of this year’s Festwochen was “Where do we come from? Where are we going?” I have already answered the first question above. If, as I suspect, the organisers were referring to the title of Gauguin’s famous painting, the motto was missing the question “Who are we?” Which is not entirely clear in the case of Eva-Maria Sens, a graduate in history and German studies, who has been collaborating with the festival since 2015, previously in the much less prominent position of head of artistic administration, and has no particularly impressive track record. For the moment her vision is not much different from the declarations of most newly appointed directors, trying to lure the audience with an open dialogue between the past and the present. It will be possible to answer the question “Where are we going?” in a few years, although it is already worrying that the festival’s musical directors will serve no more than three to five seasons. In my opinion this is too short a time to give the festival an identity and leave a clear mark of artistic individuality on it. It’s a pity, because Dantone and his Accademia Bizantina, the festival’s resident orchestra, represent the commendable trend of communicating with listeners in a purely musical language, without unnecessary fireworks, with a deep sense that the content and the emotions of compositions written centuries ago will prove intelligible also to a modern, well-prepared audience. Yet it takes time and determination to develop a new audience. Let’s hope both Dantone and his successors will not lack either.

In evaluating the entire festival, the programme of which, spread over more than five weeks, included stagings of three operas, the Cesti Competition, over twenty concerts and as many fringe events, I have to rely on the opinions of the local critics for obvious reasons. I arrived Innsbruck for the last few days of the Festwochen, consciously – albeit regretfully – forgoing Giacomelli’s Cesare in Egitto under Dantone and a concert performance of Handel’s Arianna in Creta featuring the winners of last year’s competition. I chose Christoph Graupner’s Dido, Königin von Carthago, conducted by Andrea Marcon – the operatic debut of the twenty-four-year-old composer, who not long before that got a job as a harpsichordist at Hamburg’s Oper am Gänsemarkt. The building in the square where, contrary to its name, poultry was never traded, with the name most likely referring to the estate of the landowner Ambrosius Gosen, was the first public opera house in Germany, opening in 1678, just over forty years after the inauguration of Venice’s Teatro San Cassiano. It was a stage where no castrati were hired, but where audiences nevertheless expected the same thing as in Venice: elaborate arias full of intricate embellishments and complicated librettos with lots of subplots.

Graupner wrote Dido after the departure of his younger colleague Handel, a violinist and harpsichordist at the Hamburg theatre, who before traveling to Italy had managed to present the well-received Almira and the now-lost Nero at the Gänsemarkt. Of the scores of Handel’s later “Hamburg” operas, Florindo and Daphne, only fragments have survived and they are insufficient to warrant a reliable reconstruction. The operas of Johann Mattheson – the same to whom Händel refused to give way at the harpsichord for a performance of Die unglückselige Cleopatra and was very nearly killed by the enraged composer, an event that turned out to be the beginning of a beautiful friendship between the two men – are yet to see their renaissance. The first performance in our time of Mattheson’s Boris Goudenow, which premiered in Hamburg in 1710, three years after Graupner’s operatic debut, did not take place until 2005. Of the three composers, whose oeuvres from that period perfectly reflect the “programme line” of Oper am Gänsemarkt during the house’s first heyday under the direction of Reinhard Keiser, one, Mattheson, was Hamburg-born, while the other two received their first musical training in two Saxon cities: Halle (Handel) and Leipzig (Graupner). Despite the undoubted stylistic differences, their works from the period represent German opera of the transitional phase between the mature and late Baroque, that is, according to Piotr Kamiński, “an intoxicating mixture of Venetian opera, French choreography, German heartiness and universal bad taste”.

Robin Johanssen (Dido), Jacob Lawrence (Aeneas), and Jorge Franco (Achates). Photo: Birgit Gufler

The occasional stagings of Almira aside, this eclectic genre is still a terra incognita for most Baroque opera lovers. Dido – like Almira, which does not resemble any of Handel’s later operas – surprises with its huge size, mixing of German arias and recitatives with Italian arias, typical of Hamburg opera, a range of improbable subplots and an extraordinary sensuality of sound. It also reveals the composer’s Leipzig training, especially his mastery of the art of counterpoint and fugue. The orchestration is dense and dark, combinations of instruments not obvious, changes of mood abrupt, play of modes and keys deeply thought out and linked to the character of the protagonists (most of the title role is in minor keys). Worthy of note are the elaborate ensembles and choruses, in part inspired by French composers, and in part even featuring literal references to Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas – which would confirm musicologists’ most recent theories that the father of English opera’s oeuvre had a much bigger influence on the music of continental composers than previously thought. Graupner also made several significant corrections to Heinrich Hinsch’s libretto, demonstrating an unerring sense of drama – corrections sometimes as subtle as changing the order of the chorus’ words at the beginning of Act III from “Dido lebe” (long live Dido) to “Lebe, Dido” to make the link to the following ominous duet between Aeneas and Achates, “Lebe, Dido, lebe wohl” (Farewell, Dido, farewell), all the stronger.

It’s a pity that Marcon took the accusations against De Marchi too much to his heart and opted for rather serious cuts to the score. Many arias were removed from the opera, as was the entire role of Iras, Dido’s confidante in love with Achates, with secco recitatives being drastically trimmed as well, sometimes to the detriment of the musical dramaturgy. Perhaps, however, the audience at the Tiroler Landestheater indeed was not ready yet to sit through the complete work that would have taken at least four and a half hours to perform without the cuts. In the truncated version it did hold the audience’s attention, a lot of credit for which is due to the Italian production team: the dancer and choreographer Deda Cristina Colonna who was in charge of directing (in 2017, shortly after Stefan Sutkowski’s death, her production of Lully’s Armida, presented in Innsbruck two years earlier, was brought to the Warsaw Chamber Opera), and the set designer Domenico Franchi. A sensible compromise between the sumptuousness of the historicising costumes and props, and the minimalism of the geometric, sliding decorations – magnificently lit by Cesare Agoni, who bathed the stage in vivid, saturated shades of blue, red, black, white and, above all, gold – provided space for the singers and ample room for manoeuvre for the director, who patched up the gaps in the libretto with elaborate acting gestures alluding to both Baroque dance and modern forms of dance and pantomime.

The biggest hero of the evening was, however, Andrea Marcon, leading the soloists, NovoCanto vocal ensemble and La Cetra orchestra with an energy that proved infectious to all the performers, but at the same time with precision and without falling into irritating mannerisms. He beautifully spun tuneful, expressive melodic lines, intricately weaving them into the dense, shimmering texture, only to occasionally pull out a single thread from it. He placed the accents brilliantly, played with timbre skilfully and, above all, perfectly balanced the proportions between the stage and the orchestra pit, which, given the rather uneven vocal cast, was not an easy task.

I was a little disappointed by the eponymous Dido portrayed by Robin Johanssen, a singer endowed with a sensual and fresh soprano with a charmingly silvery timbre, which to my ear is more appropriate for the classical repertoire, however. Her singing, smooth, even across the registers and confident in the coloraturas, lacked primarily specifically Baroque ornamentation. In addition, Johanssen took a long time to warm up and achieved her full expression only in Act III (especially in the harrowing aria “Komm doch, komm, gewünschter Teil”, in which she was accompanied with uncommon sensitivity by Eva Saladin, the ensemble’s concert mistress). Alicia Amo, cast in two roles – Anna, Dido’s sister, and the goddess Venus – has a soprano that is bright and rather harsh in tone, marked by a persistent, uncontrolled vibrato, which the singer tried to cover with expressive delivery of the musical text, not always succeeding. I was definitely more impressed by the velvety-voiced, very technically proficient Jone Martínez in the soprano roles of Juno and the Egyptian princess Menalippe, whose love for the Numidian prince Hiarbas, head over heels in love with Dido, would find fulfilment only after the death of the Carthaginian queen. The weakest links in the male cast were the tenors: Jacob Lawrence (Aeneas), handsome-voiced but unconvincing as a character, and the clearly still inexperienced Jorge Franco as Achates. On the other hand excellent performances came from the unfortunate suitors: Andreas Wolf, who impressed with his sonorous, well-placed bass-baritone and stylish ornamentation in the role of Hiarbas; and José Antonio López, whose noble, mature baritone was perfect for the role of Juba, Prince of Tyras infatuated with Anna.

Musica hispanica. Los Elementos, Alberto Miguélez Rouco. Photo: Mona Wibmer

I stayed in Innsbruck for two more days. The following day, at the Jesuit church, I was able to enjoy rarely heard music by two eighteenth-century composers, José de Nebra and Francesco Corselli, fragments of which – arranged in a vocal-instrumental mass typical of Madrid’s Capilla Real at the time – were performed passionately and unpretentiously by the Los Elementos ensemble conducted by the Spanish countertenor and harpsichordist Alberto Miguélez Rouco. The day after that, as part of the new “Ottavio Plus” series, Dantone and Alessandro Tampieri, concert master and soloist of the Accademia Bizantina, gave a concert at the Spanish Hall, presenting a sophisticated programme featuring works for solo harpsichord and harpsichord in dialogue with violin, viola and viola d’amore: from the “proto-Baroque” Frescobaldi, through Attilio Ariosti, Domenico Scarlatti and Johann Sebastian Bach, to the heralds of Classicism, Johann Gottlieb Graun and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

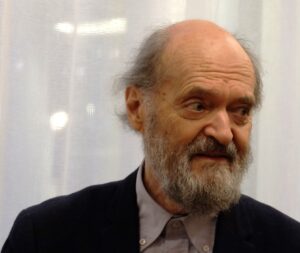

Ottavio Plus. Ottavio Dantone and Alessandro Tampieri. Photo: Mona Wibmer

The venues were packed, but pilgrimages of music lovers from abroad are yet to materialise. There are new faces among the performers, the repertoire is already a bit different, the festival is slowly changing course and setting off into the unknown. “All remains different”, the new directors announced, alluding to the hit song by the German actor and singer Herbert Grönemeyer. I hope they will keep their word. The refrain of Grönemeyer’s song begins with the words “there’s so much to lose, you can only win”.

Translated by: Anna Kijak