Antonio García Gutiérrez was born in the seaside town of Chiclana de la Frontera, in a humble craftsman’s family. His father wanted him to become a doctor, but the boy had other plans. He abandoned his studies when he was not yet twenty and decided to try his luck in the capital Madrid. He lived from hand to mouth, trying to earn a living by translating French plays by Eugène Scribe and Alexandre Dumas père. He also wrote himself without much hope of publication. He almost shared the fate of other failed men of letters: as he was about to enlist in the army, success came unexpectedly. The play El Trovador, presented on 1 March 1836 at Madrid’s Teatro del Príncipe, was so enthusiastically applauded by the audience that the author – for the first time in the history of Spanish theatre – was forced to come on stage just like in Paris. Soon Gutiérrez became famous as one of the most talented playwrights on the Iberian Peninsula. However, he did not make a fortune as a result and the same goes for his later journalistic career in the Spanish colonies in America. He returned to Europe in 1850 and scored another, even less expected success. His youthful play attracted the attention of Giuseppe Verdi, who used a libretto based on it to compose one of the most passionate – and most difficult to pigeonhole – masterpieces of 19th-century opera.

It is difficult to say why Verdi became interested in this particular work. He came across a copy of El Trovador in 1849. A lot suggests that the person who first liked the play was the composer’s partner, the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, who after several stormy affairs, unknown number of pregnancies, miscarriages and not always happy childbirths as well as magnificent though brief career became Verdi’s partner and settled with him in Busseto. Strepponi, the first Abigail, was enthusiastically applauded at the premiere of Nabucco in 1842 in Milan, but soon lost her voice. She abandoned the stage only to enter the life of the great composer, start a lifelong relationship with him and for years provide genuine support to him.

Il Trovatore, vocal and piano reduction published by Edizioni Ricordi.

Peppina, as Verdi called her, spoke several languages fluently and had a flair for literature. It is, therefore, possible that the request for a Spanish-Italian dictionary, sent by Verdi to Giovanni Ricordi, the founder of the publishing company Casa Ricordi, came, in fact, from her. The British opera historian Julian Budden has even suggested that it was Strepponi who translated Gutiérrez’s play into Italian. In any case, already in early 1850 Verdi presented the text to the librettist Salvadore Cammarano, with whom he had recently collaborated on La battaglia di Legnano and Luisa Miller. Something must have attracted him to the play and very strongly at that: for the first time he decided to compose an opera without a prior commission, without even thinking of staging it at any particular theatre. Several months before that he had finished his innovative Rigoletto, one of the most coherent and formally uniform works in his oeuvre. He expected Cammarano to approach the text with the right dose of enthusiasm and quickly produce a libretto. Things became complicated. Depressed by his father’s fatal illness, Verdi did not realise that Cammarano himself had serious health problems. He insisted. Threatened him. Put pressure on him. He asked the librettist to propose another subject, if Gutiérrez’s play had not taken his fancy. And again he argued that El Trovador was by no means as overwhelmingly sad as everybody thought, that the omnipresent death was, after all, inseparable from life. His did not expect that fate would perversely confirm his words. Salvadore Cammarano died on 17 July 1852, leaving the libretto unfinished.

The action of Gutiérrez’s play only loosely draws on historical events which in themselves were so tangled that the alleged absurdities of the source text and the final version of the libretto seem simple by comparison. The story unfolds in the15th century, shortly after the death of the King of Aragon, Martin the Humane. His eldest and only son who survived into adulthood, Martin of Sicily, also known as the Younger, died unexpectedly in 1409. Martin the Humane, who would die in less than a year, wanted to make Frederick, Martin the Younger’s illegitimate son, his successor in Aragon. He did not manage to implement his plans: the two-year interregnum ended only with the Compromise of Caspe under which the throne went to the late king’s brother-in-law, Ferdinand the Just from another dynasty, House of Trastámara.

The bastard Frederick was, in fact, the model for Count di Luna. However, Gutiérrez and, especially, Verdi were less interested in the dynastic crisis in Aragon than in the complex psychological relations between the characters. Initially, the composer wanted to call the opera Azucena and make Azucena the main protagonist of the drama. After Cammarano’s death and resumption of the work on the libretto with a young poet, Leone Emanuele Bardare, Verdi changed his original idea and decided to create a narrative with four equal protagonists: Azucena, Leonora, Manrico and Count di Luna.

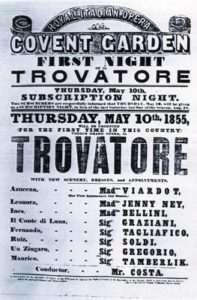

Playbill advertising the English premiere of Il Trovatore at the Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden.

The premiere of Il Trovatore, planned for Naples’ Teatro San Carlo, which was unable to bear the financial burden of the venture, eventually took place on 19 January 1853 at Teatro Apollo in Rome. The Count was sung by Giovanni Guicciardi, Manrico by Carlo Baucardé, the memorable Duke from the Turin performances of Rigoletto, while Azucena and Leonora were sung, respectively, by Emilia Goggi and Rosina Punco, who hated each other enough for the sparks to really fly during the premiere. The work was a staggering success and went on to conquer European theatres. Barely one year later it could be admired in Warsaw, where five years later it was performed in Polish. In 1857 a French version was premiered at Opéra Le Peletier in Paris with a ballet in Act III and finale reworked by the composer.

Il Trovatore has been labelled an opera with the most incoherent libretto in the history of the genre. In fact, its narrative seems to be decades ahead of its time and anticipate the sophisticated formal experiments of the masters of 20th-century cinema. The work requires maximum concentration from the spectators: we learn about all twists and turns of the action retrospectively and have to work out some elements of the intrigue from the relations between the characters. Romantic darkness hides all sorts of mysteries: the protagonists conceal both their intentions and their true identities. An allegedly dead brother emerges from the shadows wearing the costume of a mortal enemy. Leonora throws herself passionately into the arms of the Count, whom she does not love. Azucena longs for revenge and yet she proves to be a surprisingly tender carer for her adoptive son. Unbridled emotions are consumed by romantic fire: emotions of Azucena plagued by the nightmare of the stake (“Stride la vampa”) and of her adoptive child Manrico, who calls soldiers to help him save his mother being led to her death (“Di quella pira”). The driving force of Il Trovatore is a tragic conflict between Azucena’s desire for revenge, Count di Luna’s animal jealousy and Leonora’s pure, uncompromising love for Manrico. What triumphs in the finale is an irresistible temptation of vengeance. Murderous hate overwhelms any hope of reconciliation.

Illustration of a scene from Il Trovatore at the Royal Italian Opera, from the Illustrated London News.

The musical language of Il Trovatore is seemingly a step back in comparison with Rigoletto, written two years earlier. In fact, its extreme formalism highlights even more emphatically the expressive potential of the score. Spectacular choral parts, subtle cantilenas in the arias, virtuoso passages in ensembles, dazzling cabalettas – in all these elements Verdi brings the art of bel canto to an absolute peak and on the other hand he pushes the human voice to the limits of its capabilities, being accused as a result of vulgarity and “cruelty” towards singers. The Count’s baritone must combine lordly arrogance with heart-breaking lyricism. Manrico’s tenor part is one of the most difficult in the history of opera: in spite of appearances precise articulation of short notes is much more problematic for the soloist than attacking the fiendishly high notes in the famous stretta. The two main female protagonists should be sung by veritable rarities among female voices: proper strong lirico-spinto soprano and flexible dramatic mezzo-soprano with a characteristic “brassy” tone.

Verdi’s work is one of fire and darkness, there is grimy vengeance and pure jewel of unconditional love; there is blood, bile and tears. Bad-tempered bourgeois accused Verdi not only of abandoning narrative realism. They also claimed that in Il Trovatore good taste had failed the composer, that the work was not distinguished. Georges Bizet refuted these accusations brilliantly: “What about Michelangelo, Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Beethoven, Cervantes and Rabelais? Were they distinguished?”

Translated by: Anna Kijak