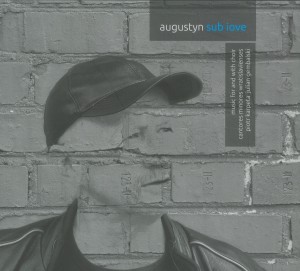

We are happy to announce that the second monographic CD of Rafał Augustyn’s music, entitled Sub Iove, and recorded by the Cantores Minores Wratislavienses directed by Piotr Karpeta, will be released in the middle of February by CD Accord Music Edition. Instead of a teaser, I post my text from the CD booklet, where I explain the whole story and give some information about the pieces included in this album. Enjoy!

***

I cannot help feeling, Phaedrus, that writing is unfortunately like painting; for the creations of the painter have the attitude of life, and yet if you ask them a question they preserve a solemn silence’ – said Socrates in Plato’s Phaedrus in the famous fragment referred to by historians of philosophy as a critique on writing (here translated by Benjamin Jowett). I also became lost in thought, when in an effort to broaden my knowledge on the subject of Rafał Augustyn’s newest contributions I turned for help to the invaluable Google search engine. First I was offered the biography of a certain race-walker, who after completing a five-year course at a technical college of gastronomy was awarded the title of a mass-catering technician. Despite all of Augustyn’s versatility I was not fooled and posed another question related to the Socrates letters. The reply came back as a mysterious 21-FP-S2-E1-TiMuz, which I initially acknowledged as a sign of solemn silence. However I persevered and after further searches discovered I was faced with a subject-cum-mode code, or more precisely the 'Text and Music’ seminar that Doctor Rafał Augustyn conducts at Wroclaw University’s Institute of Polish Philology. I was delighted by what his classes aim to achieve (’To acquire a practical ability of analyzing text-cum-musical relationships of a vocal and vocal-instrumental work in various styles, forms and circulatory systems found in musical culture’), and intrigued by the annotation in the 'Initial requirements’ column, where larger than life it reads: 'lack of formal requirements’.

Could it be that the lecturer, who discusses examples of his authorial approach to the textual-musical questions related to his own material, among others Three Roman Nocturnes and Vagor ergo sum featured on this recording, preferred to work on the mental tabula rasa of his 1st year postgraduate charges and fill it with a series of associations as loose as they are unexpected? This is somewhat if not entirely true. Augustyn values open minds. He continues to follow in the tracks of Socratic dialectics, which he considers the only source of accomplished speech – as well as accomplished composition, a characteristic ekphrasis that enters into discourse on art and our whole postmodernist world related to the principle of intertextuality. Rather than stylizing, Augustyn toys with tradition, wanders through semiotic space-time by throwing in a title here, an allusion there, and elsewhere confusing order and convention thus forcing written words and markings contained in the score to break their solemn silence and speak to the listener in a beautiful, meaningful and genuine phrase, which in effect leads to justifiable conclusions – regardless of a chosen thought process. Talking about his choral output, Augustyn descends into a somewhat schizophrenic string of free associations. In the same breath he mentions dozens of idiomatic expressions, beginning with angelic choruses, through to choirs of sirens and prisoners, ending with (if you’ll pardon the expression) 'Uncle Sam’ choruses. All in order to make us understand that hidden behind this immense inter-textual mixture of material is an attempt to impart new values to a multiple group of vocalists, associated by an average music-lover with a stringent and disciplined sense of community, whose aim is singing in praise – never mind to whom. Augustyn’s chorus has nothing in common with heavenly choirs, where as in the Book of Jeremiah – 'damned is he who badly performs the work of the Lord’. If anything it stems from ancient choreomania and is closer to poetry than composed music where melody and rhythm play an equal role dictated by the overall, over-riding 'musicality’ of the narrative. His chorus, rather than communal is usually an individual 'I’: sometimes an actor, sometimes a listener and sometimes a go-between, an authority that assists in finding the correct path in world participation – as witnessed by Nietzsche’s deliberations in The Birth of Tragedy.

This juggling act can already be seen and heard in Three Roman Nocturnes, where Augustyn exploits texts by Ennius, considered the father of Latin literature, texts by Catullus, a representative of the revolutionary Neoteric group and the philosophy of Seneca – primarily as semantic material, delighting in its sound without getting embroiled in any direct lingual-cum-historical connotations. Drawing on three Latin idioms, already established in the European cultural landscape well after the death of all three mentioned authors (Sub Iove, namely under clear skies, Sub rosa, in other words confidentially, and Sub specie aeternitatis – from a perspective of eternity), he places the choir in three different settings: in first person narrative spoken in the name of the entire humanity, in a dialectical dispute between lovers and finally in a supra-time and supra-individual narrative where the performing ensemble plays the role of a specific collective subconscious.

In Mass with a contradictory subtitle of semibrevis (a reference to one of the markings describing rhythmic values in mensural notation, but also an atypical technical description of a short Mass complemented by a Confiteor rarely exploited in musical forms) there are two identities: that of a communal, fully engaged Polish choir and a professional Latin choir. The method of building these identities – unhurried, restrained, based on a measured gradation of tensions – again recalls a form of subtle, albeit unexpected toying with early sacred music conventions, considering that the applied contrapuntal textures and the narrative’s relative lyricism go hand in hand with the subtle tone-colour effects and work on motivic material that have more in common with Bartókian modernism than Renaissance polyphony.

The identity of the four short pieces Od Sasa, provided by Augustyn with the subtitle Tones-Pauses-Events, is equally fluid and intangible, just like the identity of the texts’ author, the Wroclaw poet Dariusz Sas, well known as a Polish philologist, organizer of underground literary life and co-founder of a certain no longer existing journal for the soul, not to mention an apiarist. Sometimes one cannot be sure that he is Dariusz as in some biographical notes he leaves out his Christian name. In Epistolas (which reminds me irresistibly of a joke about an old woman, who unable to make use of the church hymn book sang at the top of her voice: “dot, dot, two dots, slash, two slashes, o Maryyyyy, etcetera”) the chorus becomes embodied molto tranquillo into the identity of four types of smoked fish sold through the retail trade, albeit slightly watered down by an outpouring of meticulously sung numbers and letter markings from a fiscal invoice. In Song for Netballers there are echoes of a stadium roar from a chorus of fans, in Autumn Malaise the multiplex lyrical subject is divided by details of home cures for a cold while in my favourite Production the chorus identifies unequivocally with Sas – a freshly baked graduate – and divulges to the listener the behind-the-scenes mass production of Polish humanists. The highly amusing Od Sasa (From Sas) are a perfect example of Augustyn’s favourite technique of applying pauses as a building tool of the musical narrative – underspecified, incomplete, with no dot over the 'I’, which is left up to the listener to place.

Augustyn spectacular journey in search of an identity for the contemporary chorus closes with a small cantata tellingly entitled Vagor ergo sum: an attempt at the impossible, namely an endeavour to tackle the unmusical poetry of Zbigniew Herbert. Augustyn would not be true to himself if in this particular spectacle of word and sound he failed to refer to the aesthetics of the theatre of the absurd – together with its uncertainty surrounding our world, its inversion of the traditional, metaphysical order of reality. Here is Herbert (or perhaps Augustyn) on a train journey across Italy, where successive legs of his trip are accompanied by station announcements related to arrivals, departures and delays of railway timetables. The chorus alternately embodies Mr Cogito, passengers, station staff, donkeys passed on the way, as well as stars and 'watery-eyed, grey foolish stalkers’, towards the end only to sing itself out quietly into the role of a sensitive soul on the final words of a Herbert prayer: 'if this is Your seduction I remain seduced for ever without forgiveness’. This is Augustyn’s musical theatre, his primary as well as his most recent fascination of creating new tonal situations out of old and discarded building blocks.

What next? A return from Herbert’s inhuman and unmusical netherworld to Plato’s two worlds? After all, he who knows what is fair, beautiful and good is not going to compose these things on running water. Rafał Augustyn’s true learning has not yet been written down. Perhaps his creative endeavour – even if supported by words – will remain forever in the sphere of agrapha dogmata, perhaps each time reconstruction on the part of the listener will be required. So much the better.

(Translated by Anna Kaspszyk)