I am happy to announce that the new album Romuald Twardowski. Songs & Sonnets – the part of the series Portraits under the label of Anaklasis, launched by PWM Editions – was published at the end of October. The CD is already available to purchase all over Europe: stay at home and go to the PWM’s online shop: https://pwm.com.pl/en/sklep/publikacja/songs–sonnets,romuald-twardowski,23970,ksiegarnia.htm. Instead of a teaser, I post my text from the album booklet here. Enjoy!

***

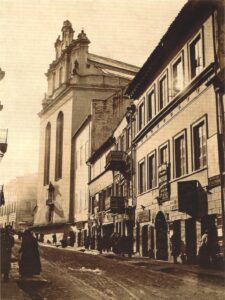

Three coincidences in succession can no longer be called a coincidence, someone said. The first working of fate is that Romuald Twardowski’s birthplace, Vilnius, was also the cradle of the Polish Romanticism, the city “one can never truly leave,” if I may paraphrase Czesław Miłosz’s poem. Before the war Twardowski spent his childhood days in the eastern part of the Old Town, in what was then Metropolitarna Street, half way between Writers’ Lane, packed full of first- and second-hand bookshops (where Adam Mickiewicz had lived following his return from Kaunas, and where he had been arrested in the autumn of 1823), and the 19th-century Georgian-style Cathedral of the Theotokos. The second ‘chance event’ took place one winter afternoon during the war, in Zamkowa Street, the main road of the medieval Vilnius. The little Romek was gazing at the window display of a music instruments shop when he was approached by a kind gentleman, who, as it turned out, was an ex-member of one of Petersburg’s orchestras. His name was Władysław Gelard. He discovered the passion for playing music in the boy, made him a gift of a violin, and gave him free lessons throughout the war. The third coincidence made Romek put his violin aside. After the war, the Holy Cross Church, abandoned by the Knights Hospitallers, was also lacking an organist. In the hope of filling this vacancy, a monk who knew Twardowski recommended him to the piano teacher Maria Zgirska, who quickly prepared the young man for further apprenticeship with organist and choirmaster Jan Żebrowski. It was also the latter who awakened Twardowski’s latent gift for composition.

Vilnius, Zamkowa Street at the beginning of the 20th century

The combination of these rather curious circumstances undoubtedly determined the life decisions of the boy from Vilnius Old Town. He studied composition with, among others, Julius Juzeliūnas at the Lithuanian State Conservatory. It is possibly to the latter that Twardowski owes his predilection for stylistic diversity, ranging from late Romantic aesthetic to dodecaphony to minimalism, and combined with an openness to the worlds of folk and traditional music. After moving to postwar Poland, he continued his music education under the guidance of one of Poland’s most eminent neo-Classicists, Bolesław Woytowicz, whose music betrays a strong influence of the French impressionism. With Nadia Boulanger in Paris he studied, first and foremost, plainchant and medieval polyphony. Twardowski frequently derived inspiration from tradition, daringly juxtaposing classical with modernist elements. He emphatically stressed his opposition to “those who preach novelty at any cost.” He created his own musical language, to which he referred, a bit provocatively, as “neo-archaism”. At the same time, though, he did not impose limitations on himself, and skilfully adjusted the character of each piece to the semantic and emotional content which it was meant to convey. His love of literature, originating in his early Vilnius years, made him highly sensitive to the word, and therefore the human voice became a nearly indispensable element of his musical language.

Choral music is undoubtedly central to Twardowski’s output. He took this genre up on a major scale in the 1950s. To him it was, as he admits himself, a way of mapping out the uncharted territories and ‘neglected areas’ in Polish music. The other wasteland which most of our avant-garde composers have failed to cultivate, but which Twardowski once entered on a similarly grand scale, was music theatre, from his ‘romantic’ opera Cyrano de Bergerac (1962) to the morality play The Life of St Catherine (1981). His solo songs are less known but equally individual in style, highly expressive and filled with internal drama, at the same time – amazingly communicative. He wrote them throughout his career. For various reasons, together they add up to a kind of highly personal, in some cases almost intimate biography of the composer.

The works selected for this CD were written over the period of two decades, in 1970–1990. All of them represent Twardowski’s fully developed, individual style, and a masterful command of musical form. In Twardowski’s songs music plays a subordinate role to the text. Sometimes it hides ‘in the shadow’ of the words in order to highlight their meanings; on other occasions it actively reinforces the text, and brings out the emotions inherent in the lines of verse. Such an approach comes as no surprise if we consider the high calibre of the poetry taken up by Twardowski. Sonnets by Michelangelo (1988) are settings of three late poems by one of the greatest artists of the Italian Renaissance, in congenial Polish translations by Leopold Staff. Twardowski speaks here with his own language, albeit strictly subordinated to the moods of the aging Michelangelo, fascinated with the beauty and sensitivity of the nobleman Tommaso dei Cavalieri, affected by the inevitable passage of time, and torn between “fear and the phantoms of love and death.” Three Sonnets to Don Quixote, written two years later, constitute a similar homage to another Renaissance master, this time – a Spanish one. The title is a bit misleading, since in fact they are two sonnets plus a verse epitaph in honour of the knight errant. Nevertheless, all of them were written by Miguel de Cervantes and incorporated into his famous novel. Twardowski makes effective use of Anna Ludwika Czerny’s first postwar translation of Don Quixote, turning these three poems into a bitter-sweet musical portrait of a certain nobleman whose “brain got so dry” for lack of sleep and too much reading that “he finally lost his sense.” These provocatively ‘Woytowicz-like’ songs, rooted in the spirit of French music, attracting the ear with the freshness and wealth of various shades of sound – could well serve as a complement for Ravel’s last unfinished masterpiece, the cycle of three songs Don Quichotte à Dulcinée.

Composed a little earlier, in 1987, Three Songs to words by Stanisław Ryszard Dobrowolski may seem to be ‘lighter weight’, but they conceal a secret hinted at in their very sequence, which represents a progression from lyrical reflections on the departure of the beloved to the playful experience of reality in The Warsaw Sparrows, to the broad and familiar humour of Non è vero, sung ‘straight into the ear’. The other three cycles, despite variable atmosphere, are quite serious and can be read as miniature treatises on nostalgia, longing, and the sorrows of parting.

From the Viliya (1990) to words by Helena Massalska-Kołaczkowska, co-founder of Polish Radio Song Theatre and author of the lyrics of Alfred Gradstein’s late 1940s hit A Bridge to the Left, a Bridge to the Right as well as of several children’s fables set to music by Ryszard Sielicki, is a cycle dedicated by Twardowski to his mother Paulina. In these three brief songs, filled with references to Lithuanian folklore, the composer returns to the city of his childhood; to the Green Lakes near Vilnius, whose water owes its unusual colour to minerals washed off the chalk bottom; to the Łukiski (now Lukiškės) Square, where the famous Kaziuki fair has been held annually on St Casimir’s Day, complete with jugglers and people in fancy dress; and, finally, to the shore of the icebound Viliya, where sleigh rides with torches were held in the winter.

The five-part Face of the Sea (1979) to poems by Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, Jacek Łukasiewicz, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, and Kazimierz Sowiński, can be considered, in some ways, as an echo of Twardowski’s earlier opera Lord Jim, where the composer employed the wistful motif of undulating sea waves. On the other hand, this cycle is part of the wider ‘seafaring’ trend known from that period.

The profoundly moving Trois sonnets d’adieu to words by three French poets of the late 16th and early 17th centuries (a mannerist, a libertine, and a member of La Pléiade) were composed in 1970, directly after the tragic and still unexplained death of composer Elisabeth Tramsen, Twardowski’s fiancée, the eldest daughter of a Danish surgeon who in 1943, as a member of an international committee, had conducted the autopsies of Polish officers, victims of the Katyn Massacre. Originally composed for bass-baritone and chamber orchestra, this cycle, and especially its last element, the sonnet by Pontus de Tyard in Wisława Szymborska’s phenomenal translation – serves as an excellent conclusion for the entire tale told on this album. “Come, much craved Sleep, wrap around my flesh / since I sincerely accept your cherished nightshade and poppy.” The end turns out to be a beginning. Sleep has come at last, and has dispelled anxiety, bringing genuine solace. Now everything could start over again.

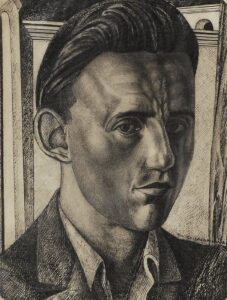

Jan Kaczmarkiewicz: Portrait of a young composer (Romuald Twardowski)

The album has been programmed and the songs performed by Tomasz Konieczny, who is a great fan of Romuald Twardowski’s songs and a sincere enthusiast of the poetry set by this composer. It is thanks to Konieczny’s initiative that we can see how also in this field, much depleted after the war, Twardowski proved to be a skilful gardener. This may be why he never truly left Vilnius, either mentally or in his heart. It was in that city that Stanisław Moniuszko had settled for good in 1840 after his wedding to beloved Aleksandra née Müller, met several years earlier at a noblemen’s inn situated in Niemiecka Street. From Vilnius, Twardowski recalls the scattered pages of Moniuszko’s Songbook for Home Use, left behind in the turmoil of war and kicked around in the streets. Someone had to pick those pages up, and reassemble them into his own, quite separate songbook of life.

Translated by: Tomasz Zymer