Współkochać przyszli, nie współnienawidzić

W połowie maja 1968 roku, dwa dni po zajęciu Sorbony i rozpoczęciu strajku powszechnego we Francji, Jean-Louis Barrault otworzył bramy Odéonu przed kilkutysięczną rzeszą demonstrantów. Nie podejrzewał, że wydarzenia rewolucji lipcowej roku 1830, kiedy teatr stał się jednym z głównych ośrodków aktywności ówczesnej zbuntowanej młodzieży, powtórzą się w spotworniałym kształcie i wymkną spod kontroli. W Dzielnicy Łacińskiej stały już pierwsze barykady z samochodów, zwalonych drzew i mebli wyniesionych z uczelni. Na ulicach powiewały czerwone sztandary socjalistów i czarne flagi anarchistów, w powietrzu unosiły się opary gazu łzawiącego. Protestujący studenci zrywali pokrywy z miejskich kubłów na śmieci, żeby używać ich jako tarcz w starciach z policją. Dołączali do nich artyści, intelektualiści i coraz liczniejsze grupy agitatorów. W nocy z 16 na 17 maja Barrault zanotował w swoim dzienniku: „czujemy się zdradzani i nie mamy ochoty opowiadać się po niczyjej stronie. Wzruszają nas tylko prawdziwi studenci. Wydaje mi się, że zostali zdradzeni tak samo jak my”.

Rewolta we Włoszech zaczęła się dużo wcześniej i trwała znacznie dłużej, od 1966 aż do jesieni 1969 roku. Przetoczyła się przez uniwersytety w całym kraju, od Mediolanu i Turynu, przez Neapol i Padwę, aż po Genuę i Salerno. We Włoszech – w przeciwieństwie do Francji – ruch studencki zrósł się od początku z ruchem robotniczym. Studenci pomagali strajkującym redagować ulotki i organizowali wspólne spotkania, żeby analizować przebieg wydarzeń i snuć strategie na przyszłość. Rząd skupił się przede wszystkim na torpedowaniu działalności skrajnej lewicy. Zlekceważył ekstremistów z drugiej strony, między innymi radykalny, neofaszystowski odłam Ordine Nuovo. W grudniu 1969 dwóch członków organizacji dokonało zamachu bombowego na Piazza Fontana w Mediolanie. Zginęło siedemnaście osób. We Włoszech skończył się „pełzający maj”, zaczęły się „lata ołowiu”.

Sto dwadzieścia lat wcześniej, w 1848 roku, gdy w Mediolanie wybuchły zamieszki nazwane później „Cinque giornate”, Verdi przebywał akurat w Paryżu. Na wieść o powstaniu wyruszył do Lombardii i dotarł na miejsce 5 kwietnia, dwa tygodnie po zakończeniu zrywu. W liście do Francesca Piavego oznajmił, że jest pijany ze szczęścia po zwycięstwie buntowników i nie zamierza marnować papieru na komponowanie, skoro lepiej go użyć do produkcji łusek do pocisków. Pyrrusowe to było zwycięstwo. Mediolańczycy ponieśli przeszło dwukrotnie większe straty niż przepędzeni przez nich Austriacy, którzy i tak wrócili do miasta w lipcu. Risorgimento dobiegło kresu dopiero w 1871 roku i nie skończyło się zjednoczeniem wszystkich ziem zamieszkanych przez Włochów. Rok 1968 zmienił oblicze świata, ale wciąż jest tylko jednym z kamieni milowych na nieprzebytej drodze do zjednoczonej Europy.

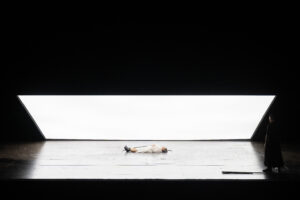

Rivoluzione, scena zbiorowa. Fot. Karl Forster

Jacques Mallet du Pan był rojalistą, ale słusznie przyrównał rewolucję do pożerającego własne dzieci Saturna. Tym tropem poszedł Krystian Lada w swoim najnowszym przedsięwzięciu, zrealizowanym na zamówienie brukselskiej La Monnaie i jej szefa Petera de Caluwe. To już druga na tej scenie – po dobrze przyjętej Bastardzie według koncepcji Oliviera Fredja – próba wskrzeszenia barokowej konwencji pasticcio. O ile jednak zamysł Bastardy polegał na wyodrębnieniu wątku królowej Elżbiety z czterech oper Donizettiego i sklejeniu ich fragmentów w nową, wciąż „tudorowską” całość, o tyle Lada posunął się znacznie dalej, tworząc rasowe pasticcio: całkiem nową opowieść opartą na materiale muzycznym z szesnastu oper Verdiego, powstałych w początkowej fazie walk o zjednoczenie Włoch. Pierwsza część dyptyku, Rivoluzione, rozgrywa się w burzliwej scenerii rozruchów 1968 roku, druga, Nostalgia – czterdzieści lat później, kiedy wspomnienia rewolucji odżywają na pewnym wernisażu, pod wpływem nawiązującej do tamtych wydarzeń instalacji rzeźbiarskiej.

Pomysł szalony, wymagający benedyktyńskiej pracy dramaturgicznej i pieczołowitego wyboru dostosowanych do koncepcji fragmentów (zaczerpniętych między innymi z Oberta, Ernaniego, Stiffelia, I Lombardi alla prima crociata, Attili, I due Foscari, Giovanny d’Arco i Un giorno di regno, ale także z Nabucca i Makbeta), a mimo to udany i – paradoksalnie – pod wieloma względami prawdziwie „verdiowski” z ducha. Jeśli purystom czegokolwiek zabrakło, to skomponowanego specjalnie na tę okoliczność muzycznego spoiwa, które nadałoby obu częściom pozór „prawdziwej” XIX-wiecznej opery. Lada poszedł jednak inną drogą, łącząc poszczególne elementy filmowymi wstawkami z udziałem śpiewaków w mówionych interakcjach i monologach, dzięki czemu uniknął „skażenia” muzyki Verdiego jakimkolwiek obcym ciałem muzycznym. I zapewne postąpił słusznie: mozaikowość użytych środków teatralnych znacznie lepiej pasuje do wykoncypowanej przez niego narracji, przedzielonej czterdziestoletnią cezurą, wciąż jednak osadzonej w nieodległej przeszłości.

W Rivoluzione akcja pędzi naprzód jak tłum rozjuszonych demonstrantów. Lada fenomenalnie rozgrywa sceny zbiorowe, wplata w akcję fragmenty dokumentalnych filmów z epoki, wzmacnia wydźwięk arii, cabalett i ansambli udziałem tancerzy ulicznych (znakomita choreografia Michiela Vandevelde). W jak zwykle czystej przestrzeni scenicznej (autorem całej koncepcji jest Lada, w realizacji scenografii i materiałów wideo wspierany odpowiednio przez Łukasza Misztala i Jérémy’ego Adonisa; kostiumy zaprojektował Adrian Stapf), znakomicie oświetlonej przez Aleksandra Prowalińskiego, przędzie się nić iście verdiowskiej intrygi. Osiową postacią jest stoczniowiec Carlo, przyjaciel Giuseppe, studenta inżynierii i syna wpływowego oficera policji. Ich „niewłaściwa klasowo” relacja wynika ze wspólnego zamiłowania do boksu. Giuseppe chodzi z Cristiną, studentką szkoły filmowej, która wciąż nie może się wyleczyć z dawnej miłości do Carla. Laura, siostra Giuseppe, studentka klasy skrzypiec, związana z zakochanym w niej po uszy pianistą Lorenzem, ulega narastającej fascynacji zabójczo przystojnym Carlem i porzuca burżuazyjne ideały na rzecz haseł rewolty. Wszystko zmierza do dramatycznego finału na barykadach: Laura popełnia samobójstwo i decyzją tłumu dołącza do korowodu wielkich męczenników rewolucji.

Rivoluzione. Nino Machaidze (Laura). Fot. Karl Forster

Ta historia mogłaby dziać się w dowolnym miejscu ówczesnej Europy: w Paryżu, Mediolanie, rozjeżdżanej czołgami Pradze, a nawet marcowej Warszawie. Źródeł inspiracji Lady można by doszukiwać się w Marzycielach Bertolucciego albo w filmach francuskich reżyserów Nowej Fali. Tyle że prościej odnaleźć je we wczesnych operach Verdiego, w których nieustannie rozbrzmiewa „muzyka karabinów i armat”, a młodzieńcze ideały ścierają się z porywami równie młodzieńczych uczuć w skomplikowanych wielokątach miłosnych. Lada wykorzystał potencjał Verdiowskiej konwencji do cna. Laurze powierzył partie przeznaczone na sopran o zabarwieniu dramatycznym, Cristinie – odpowiednie dla śpiewaczki wiernej tradycji włoskiego belcanta spod znaku Donizettiego i Belliniego. Charyzmatyczny Carlo jest typowym verdiowskim tenorem, Giuseppe, bohater niejednoznaczny, śpiewa stosownym dla tej postaci barytonem. Nośnikiem gniewu i zawiedzionych uczuć Lorenza jest głos basowy.

Lada z niebywałą wrażliwością „złamał” tę konwencję w rozgrywającej się czterdzieści lat później Nostalgii. Nie ma już Cristiny. Jej córka Virginia odziedziczyła po zmarłej matce zamiłowanie do sztuki filmowej, subtelną urodę i nie mniej subtelny głos (Lada obsadził w tej roli tę samą śpiewaczkę). Bohaterowie się postarzeli. Carlo śpiewa barytonem, Giuseppe basem, Lorenzo przestaje śpiewać w ogóle (basa zastąpił aktor Denis Rudge). W tenorze Icilia, zaangażowanego politycznie artysty, pobrzmiewa odległym echem głos młodego Carla. Na scenę wkracza Donatella, właścicielka galerii sztuki, która urządza podwójny wernisaż filmu Virginii i rzeźby jej chłopaka Icilii, zatytułowanej „Barykada 1968”. Ten archetyp verdiowskiej primadonny sprowokuje w finale katharsis na miarę antycznej tragedii: bezwiednie uświadomi Virginii, kto jest naprawdę jej ojcem, przywoła z zaświatów ducha Laury, wyzwoli w trzech starych mężczyznach uśpioną energię, każe im zniszczyć dzieło Icilii i rozpędzić demony rewolucji, która pożarła wszystko, co kiedyś kochali.

Kilka obrazów z tego dyptyku głęboko zapadło mi w pamięć: cielęcy zachwyt dziewczyny na widok atomowego grzyba, zdławiony po chwili bezbrzeżnym smutkiem chóru „Patria opressa” z Makbeta; finał trzeciego aktu Rivoluzione, przywołujący na myśl upiorne skojarzenia z Tratwą Meduzy Géricaulta i kilkoma płótnami Delacroix; symboliczny koniec Nostalgii, w którym Lorenzo próbuje ocalić z orgii zniszczenia gipsowe popiersie Verdiego. Po raz kolejny zetknęłam się z ultranowoczesnym teatrem operowym, precyzyjnie wyreżyserowanym, misternie złożonym z mnóstwa idealnie pasujących do siebie kawałków, a zarazem odnoszącym się do spuścizny kompozytora z wiernością graniczącą z hołdem.

Ogromna w tym zasługa wszystkich uczestniczących w tym przedsięwzięciu muzyków, przede wszystkim dyrygenta Carla Goldsteina, łączącego podziwu godną znajomość Verdiowskiego idiomu ze zmysłową żarliwością interpretacji. W partii Laury świetnie wypadła Nino Machaidze, śpiewająca nieskazitelną emisją, sopranem potężnym i doskonale rozwiniętym w górnym odcinku skali, choć niezbyt nośnym w średnicy. Enea Scala, obdarzony tenorem soczystym i niezmordowanym, idealnym do roli Carla w Rivoluzione, mógłby odrobinę wyraziściej różnicować dynamikę, ten drobny mankament złożę jednak na karb zapału, który pozwolił mu zbudować tym bardziej przekonującą postać młodego buntownika. Scott Hendricks, jego starsze wcielenie w Nostalgii, dysponuje barytonem niedużym i dość chropawym, co w drugiej części dyptyku należy paradoksalnie uznać za atut. Obydwaj wykonawcy partii Giuseppe, baryton Vittorio Prato i bas Giovanni Battista Parodi, wywiązali się ze swych zadań bez zarzutu. Podziwiam siłę wyrazu interpretacji Justina Hopkinsa (Lorenzo), choć jego ciemny, aksamitny bas zdecydowanie zyskałby na urodzie, gdyby artysta nie miał skłonności do śpiewu na obniżonej krtani. W niewielkiej roli Icilia dobrze się sprawił Paride Cataldo, obdarzony dźwięcznym i bogatym w barwie tenorem lirycznym.

Nostalgia. Scott Hendricks (Carlo) i Helena Dix (Donatella). Fot. Karl Forster

Najlepsze jak zwykle zachowałam sobie na koniec. Sensacją dyptyku okazała się Gabriela Legun w podwójnej roli Cristiny i Virginii, fenomenalnie uzdolniona polska sopranistka, zwyciężczyni Konkursu imienia Ady Sari w 2019 roku, której wróżę piękną międzynarodową karierę. Złocisty, miękki głos Legun już teraz imponuje nieskazitelną techniką, a jeśli jej interpretacje są jeszcze chwilami „przezroczyste”, z pewnością nabiorą ekspresji w miarę gromadzenia przez nią doświadczeń scenicznych. Drugą perłą w wokalnej koronie Rivoluzione e Nostalgia była niewątpliwie Helena Dix (Donatella), obdarzona giętkim, zmysłowym, prawdziwie verdiowskim sopranem, którym włada na tyle świadomie, by z wielkiej sceny szaleństwa Lady Makbet uczynić zarazem olśniewający popis bel canto, jak i przewrotną parodię związanej z tą rolą konwencji. W dzisiejszych teatrach operowych rzadko się trafia tak celne połączenie znakomitego śpiewu i wybitnej gry aktorskiej z niezrównanym poczuciem humoru.

Jean-Louis Barrault pisał niedługo po wydarzeniach majowych 1968 roku, że ulice Paryża zagarnęła nienawiść, że ludzie długo nie będą mogli sobie uświadomić doniosłości i konsekwencji tamtych wydarzeń. Chyba już przyszła pora. Krystian Lada i współtwórcy sukcesu jego brukselskiego dyptyku zaczęli wygrzebywać spod tamtej nienawiści pierwsze okruchy miłości – tej, która zginęła, tej, która odżyła po latach, i tej, która trwać będzie wiecznie. Jak w muzyce Verdiego, która okazała się idealnym wehikułem opowieści o całkiem innych czasach.