Spring has returned again. The earth

is like a child who’s memorized

poems; many, so many … It was worth

the long painful lesson: she wins the prize.

Her teacher was strict. We liked the white

in the old man’s whiskers.

Now when we ask what green or blue is, right

away she knows, she has the answer!

Earth, lucky earth on vacation,

play with the children now. We long

to catch you, happy earth. The happiest will win.

Oh what her teacher taught her, all those things,

and what’s imprinted on the roots and long

complicated stems: she sings it, she sings!

Rainer Maria Rilke, The Sonnets to Orpheus, I, 21, tr. A. Poulin.

The Feast of the Annunciation

On the Feast of the Annunciation, falling on 25 March, shortly after the arrival of the astronomical spring, the earth would open itself up to receive the seed. In eastern parts of Poland, that moment was celebrated as the Day of Our Lady of Opening (Matka Boska Roztworna), who helped worms to emerge from the soil, streams to burst through splitting ice, the mouths of frogs and snakes to open, bees to awaken in their hives and storks to return to their nests. Peasants would release their flocks onto barely green pasture. They would symbolically fertilise the earth, sowing it with pea seeds, irrepressible in their will to sprout. They would repair storks’ nests and have the womenfolk bake ‘busłowe łapy’ – ritual cakes in the shape of birds’ feet, which they then placed in those nests to precipitate the arrival of the sluggish spring. From the same dough, the women would also form shapes like human legs, which, after baking, they would distribute to unmarried maidens, so that they might, on healthy pins and as quickly as possible, marry hard-working men. At this time of the year, the cycle of life and death came full circle. Over Our Lady of Opening hung the memory of the old pagan cult of the dead. The earth opened up not just to take seed, but also to free the ancestors’ souls, trapped by the winter, and enable them to return to their own domain. Particular care was taken with new, fragile life, as if out of fear that mortals’ meddling would nip that life in the bud. Eggs set to hatch would not be touched, and grain seeds and potato tubers were left in peace for the day, so that water and light would draw forth their sprouts by themselves. It was forbidden to spin or to weave, and poppy seed would be strewn around houses to ward off evil forces. People waited for the slow miracle of birth: new crops from the seed-laden earth, new livestock from inseminated herds, new people from women’s wombs. The world rose from the earth, before returning to it once again.

Towards the end of March, the earth really does open up. It does not even need to be mutilated with a plough. In the warm rays of the sun, enigmatic telluric creatures – protozoa and fungi – produce substances which the human nose associates with the smell of soil. Before more easily comprehensible aromas appear in the vernal world – the scent of opening blossom, of leaves bursting from buds, of the slime-covered coats of newborn calves – the source of our inexplicable annual euphoria are odours spurting from the still tawny earth, the same earth in which, before the winter, we buried the remains of the previous life. For something to be born, something must die.

The Great Goddess

I am not a philosopher. My ancestors were peasants, and I have inherited from them a superstitious veneration for the rich March soil, ready to take the seed, stinging one’s nostrils with a smell as sensuous as the truest pheromone. I later transferred that simple peasant sensibility, on occasion, to my literary acre, cultivated just as conscientiously and with a respect for certain taboos, as did the Podlasian peasants of yore. Not long ago, I suggested that Roger Scruton, author of the recently published The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, and John Eliot Gardiner, praised by the critics for his monograph Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, write so sagely about music because they associate the labour of composing with the eternal cycle of the seasons, with begetting, surviving, sustaining life and dying, because they see the composer as a farmer, who cannot bring a masterwork into the world without occasionally spattering himself with soil and manure.

Yet before I matured into reading philosophers, I was already troubled by the paradox of the state that obtained prior to the ordering of the elements of the universe. How to imagine nothing? How to get one’s head around the existence (or non-existence?) of the Chaos from which the original Greek deities, the protogenoi, arose? Was Chaos a void, a yawning chasm, or – as Hesiod’s Theogony suggests – also a place, or even a being capable of procreation? Did Gaia – the ‘wide-bosomed’ Mother Earth – emerge out of nowhere? Was she the firstborn of some undefined Chaos? One way or another, that mighty, self-regulating being gave birth to dozens of other gods – by herself, under various guises, of amorous union with her sons, grandsons and great-grandsons, from the blood and seed of the mutilated Uranus. From her womb, she pushed forth mountains and seas, hundred-handers and titans, rebels, avengers and ash-tree nymphs, the guardians of foundlings. Wagner’s Erda bears traits of both the Greek Gaia and the Nordic Jörð, an icy giantess personifying the earth, lover of the world’s co-creator Odin, who only gained the status of father of the gods in Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda.

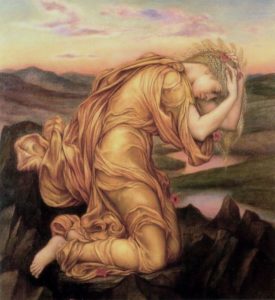

Demeter mourning for Persephone, by Evelyn De Morgan.

Attempts to personify any Great Goddess were beyond the powers of my imagination. Whenever I heard Erda’s words from Das Rheingold (‘I know all that was, is and will be’), I was overcome by a metaphysical fear. Yet the presentiment grew within me that the World – understood as the reality around me – was something other than the mysterious, secretive Earth that alternately opened and closed, that all art, including music, must arise somewhere on the edge of existence, must erupt from the depths, like a stream of headily aromatic organic compounds, must mature beneath a thick layer of humus, germinate and be born of some primary, telluric impulse – spontaneously, in a way not entirely predictable, even for the creator.

And then I began to read Martin Heidegger.

The dispute between the earth and the world

In The Origin of the Work of Art, based on a series of lectures given in Zurich and Frankfurt during the 1930s, Heidegger considers the essence of creative activity in terms of being and truth. In every work of art, a fierce dispute rages between the World and the Earth. The World – the great and the small, the world of the individual, the world of one’s family, the world of a larger community or of a whole nation – is revealed in creative output. The work of art adopts the role of the subject, itself creating such ‘worlds’ big and small, and at the same time opening them up to the beholder. In its deepest layer, however, the work refers to the Earth, marked by being its own essence, yet itself remaining concealed. It is the backdrop, the foundation, on which every creative artist writes, paints or composes his or her own world:

'To the work-being belongs the setting up of a world. Thinking of it from within this perspective, what is the nature of that which one usually calls the ‘work-material’? Because it is determined through usefulness and serviceability, equipment takes that of which it consists into its service. In the manufacture of equipment – for example, an ax – the stone is used and used up. It disappears into usefulness. The less resistance the material puts up to being submerged in the equipmental being of the equipment the more suitable and the better it is. On the other hand, the temple work, in setting up a world, does not let the material disappear; rather, it allows it to come forth for the very first time, to come forth, that is, into the open of the world of the work. The rock comes to bear and to rest and so first becomes rock; the metal comes to glitter and shimmer, the colors to shine, the sounds to ring, the word to speak. All this comes forth as the work sets itself back into the massiveness and heaviness of the stone, into the firmness and flexibility of the wood, into the hardness and gleam of the ore, into the lightening and darkening of color, into the ringing of sound, and the naming power of the word.

That into which the work sets itself back, and thereby allows to come forth, is what we called ‘the earth’. Earth is the coming-forth-concealing [Hervorkommend-Berdende]. Earth is that which cannot be forced, that which is effortless and untiring. On and in the earth, historical man founds his dwelling in the world. In setting up a world, the work sets forth the earth. ‘Setting forth [Herstellen]’ is to be thought, here, in the strict sense of the world. The work moves the earth into the open of a world and holds it there. The work lets the earth be an earth.’ (Martin Heidegger, ‘The origin of the work of art’, in Off the Beaten Track, ed. and tr. Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes, CUP, 2002, 24.)

Heidegger’s way of seeing art is exceptionally close to my heart, although I would not myself express it in such a florid language of metaphors resulting from a conviction that it is impossible to illuminate the essence of being through the traditional language of European philosophy. In all creative output, the same occurs: the composer transfers that which lies hidden in the earth to ‘the open’ of the world. He explores its mystery as far as the earth allows him to. If everything was pulled from it, if everything was consumed and exposed to the merciless inspection of the world, the earth would cease to exist. And the world would cease to exist. The one is inextricably linked to the other. Worlds, microworlds and communities have no raison d’être in isolation from the original mystery of the earth; the earth’s secret would lose all its charm if the world did not strive to ‘hold it in the open’.

The earth as thus understood on one hand bears all the hallmarks of the Dionysian element, fiercely defending access to its secret, which it reveals only at the right time and in suitable circumstances. On the other hand, it holds the unshakeable foundation of all human existence, including artistic existence. Every person connected with music cyclically experiences the phenomenon of the Feast of the Annunciation. The composer ponders the source of inspiration freed from beneath the ice as he might a damp, freshly turned ridge of soil. He imbibes the intoxicating scent of something that he does not entirely understand. In a crucial moment of forgetting, he throws himself from the heights of Apollonian order into Dionysian ecstasy. In order to create something truly new, he must first kill his Orpheus, cut off his head, tear the singer to pieces – like a horde of crazed Maenads. Only then will the seed germinate. The performer must lavish particular care upon that harbinger of new life: first leave it in peace, until the interpretation matures, then carefully cast the seed into the furrow and immediately rake it over, to prevent the earth drying out. It only remains for the listener to observe how the delicate plant grows: to feed it with soil, to clear the weeds around it and finally to reap the harvest. This slow recurring miracle of the birth of a musical work has been going on forever. Works emerge from a ridge of inspiration, go out to pasture and then grow old and die irrevocably – or else they move back and forth between the openness of the world and the closedness of the earth, like Persephone in her eternal wandering between Hades and Demeter.

Alienation

The closer we come to the present day, the more difficult it is to associate the earth with fecundity, as the giver of all life, a mighty and imperturbable carer. It becomes increasingly difficult to spin out a musical narrative in the peasant rhythm of the seasons, to paint the beauty of creation in a language referring directly to natural phenomena. There will be no more breathtaking Haydnesque tableaux of the birth of light and humankind – as in The Creation – or the sensuous earthly theatre that exudes from the score of the Symphony in G minor, No. 39, one of the first compositions associated with the ‘storm and stress’ period in his oeuvre. There will be no more wonderful ‘Pastoral’ than the one created by Ludwig van Beethoven – a composer who preferred to spend his time in the company of trees than people.

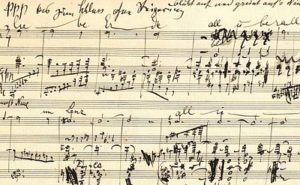

Gustav Mahler, the autograph manuscript of the piano reduction of Der Abschied from Das Lied von der Erde.

At a certain moment in time, musicians stopped singing of the earth and began to yearn for it, to bid it farewell, to feel alien upon it, as if oblivious to the sensuous aroma of ploughed furrows in March, overcome only by the November smell of burned leaves and rotting stubble. Such is the portrait of the Great Goddess, deep in mourning, that emerges from the pages of Das Lied von der Erde, written by a Gustav Mahler crushed by the anti-Semitic witch-hunt at the Staatsoper in Vienna, broken by the death of his beloved daughter Maria, alarmed at the diagnosis of a congenital heart defect. ‘Mein Herz ist müde’ (‘My heart is weary’), sings in the second song the Lonely One, for whom the autumn is dragging on too long. Reflected in the mirror of ‘Mahler’s most wonderful symphony’, as Leonard Bernstein called The Song of the Earth, is a forgotten masterwork by another Viennese modernist: Alexander von Zemlinsky’s Lyrische Symphonie, a cycle of seven songs with orchestra to words by Rabindranath Tagore. Mahler, in his composition, used translations of Chinese poetry from Hans Bethge’s anthology Die chinesische Flöte. Zemlinsky turned to the output of the Indian Nobel Prize winner. Both sowed their scores with beautiful and swollen, but foreign seed. Both had the two soloists sing of the torment of separation and disappointment in love, trudging through the entire narrative utterly alone, without meeting one another even in the middle of the laboriously tilled field.

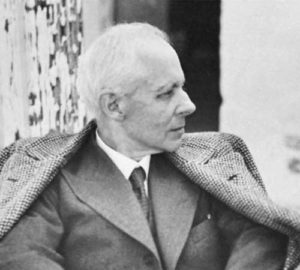

A further association is evoked by the music of Béla Bartók – an urban seed, which gave a fertile crop on the field of Hungarian folksong, dug over for centuries. Bartók’s plants sent their roots deep down, shattering rocks hidden in the subsoil, flowering with a rampant, original harmonic language, which depicts equally distinctly the horror of Judith, the torment of Duke Bluebeard and the cruelty of the pimps mistreating the Chinese mandarin, kept alive by his desire for a beautiful streetwalker.

Béla Bartók

Strength

The earth has grown old. It has begun to yield its fruits in pain, to lament its lovers, the lost harvest of its passions, the arduous years – exhausting, but beautiful in their simplicity – when the pea always sprouted in the swollen furrow, the bees always woke in their hives, and the storks unerringly returned to their patched-up nests, filled with ritual cake. And yet, in spite of everything, it continues to open its bosom and to lure, with its mystery, creative artists who crave to move it and hold it in the open of their world. And often – having drunk its fill of their love – it leaves them defenceless, disorientated, unaware of where their inspiration came from and why it deserted them, having found a path in other regions … for instance, under the roof of the castle belonging to Gabriel Branković, one of the protagonists of The Architect of Ruins, a now irreverent, now deadly serious Dedalus novel by the recently deceased Austrian writer Herbert Rosendorfer. Branković turns out to be a vampire, craving spiritual immortality, and his victim is the brilliant young composer Felix Abegg:

‘Although tired from the ride, Felix began his composition that night, a choral work called “The Hours”, a setting of a poem by a certain Raimund Berger […] The poem, in short stanzas, consists of prayers for the Hours of a night watch from the ninth Hour through to the ninth Hour again. The first verse,

O Babel, tower to man’s pride,

God’s wrath hath scattered far and wide! …

was sung by the whole choir in unison, to an apparently simple chorale-like melody. In the following verses the voices divided into combinations ever more rich in meaning and harmony. Inversion, regression and complex interweaving built up into a carpet of counterpoint in which, as if by chance, at particular points where the voices converged like carefully-placed knots, there appeared the pattern of a melody that was not sung by any one single voice and yet was clearly audible. Then in,

At the first hour

A call resounds and echoes o’er

The plain: “This once and then no more” …

the piece reverted to a powerful unison, which was renewed with each Hour until it reached its resolution at the return of the “Ninth Hour”,

The long dark night of sin is past:

On Golgotha – redeemed at last.

Felix had long since worked out the piece, had composed it in his head during the long rides through the forest, with all the subtle play of counterpoint, and had then let it rest in the womb of his remarkable memory until this night, when he set about putting it down on paper, not suspecting that someone else had already done so.

Again the Foehn was raging and tearing at the shutters. Felix sat for a long time at his table writing until, once again, it seemed that the wind had loosened one of the shutters from its catches. He went to the window. Outside – it was a very steep drop, the tops of the tallest spruce trees did not reach the overhang – outside on the narrow window-ledge sat Brankovic. Scarcely had Felix torn open the window than the Professor scurried head first on all fours down the precipice. Felix saw him disappear into the seven-sided oriel window …

The next morning Abegg woke to find himself in his bed, although he could not remember how he got there. On the table lay the manuscript, completed in a similar, yet different hand.’ (Tr. Mike Mitchell)

***

The conclusion? Listening closely to the whisper of the open March earth, one must be alert. Sometimes, its mysteries lie too deep. Just a moment’s inattention, and it will close over the reckless creative artist and, with the malice of an old woman, betray its secret to somebody else. I admire the earth, and I love the music that flows from the depths of its primeval entrails. Only sometimes I fear her a little.

Translated by: John Comber