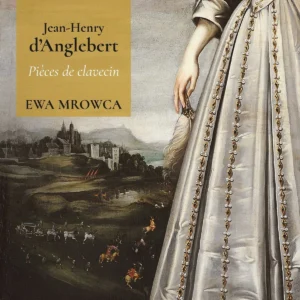

Less than a fortnight ago, on 18 April, Ewa Mrowca premiered her new album of Pièces de clavecin by d’Anglebert at the Actus Humanus festival in Gdańsk: with a solo recital on an instrument made in 2020 in Castelmuzio by Bruce Kennedy – a copy of the harpsichord by Joannes Ruckers (Antwerp, 1624), rebuilt in France a century later. Now I am delighted to announce the aforementioned CD, the value of which I fully vouch for, and in which I have my modest contribution in the form of an essay in the booklet: Jean-Henry d’Anglebert / Pièces de clavecin / ACD 346. Below you will find some useful links. Enjoy reading, enjoy listening even more, and have a beautiful May Day.

https://found.ee/ACD346

https://soundcloud.com/actushumanus/ahr2025d3

https://www.polskieradio.pl/8/8339/artykul/3367482

***

Connoisseurs of the printing art agree that d’Anglebert’s Pièces de clavecin, a set of four harpsichord suites published under the composer’s imprint in Paris (1689), is one of the most finely engraved keyboard music collections to have come out in the entire seventeenth century. That elegant, almost square volume (19 x 21.5 cm) comprises 135 pages, seven of which contain splendidly illustrated introductory matter. As the title page informs, the tome comprises ‘pieces for harpsichord, composed by Jean-Henry d’Anglebert, ordinaire de la musique de la chambre du Roy, completed with performance manner, including diverse chaconnes, overtures, and other works by Mr Lully arranged for that instrument, several fugues for the organ, and indications concerning the accompaniment. Volume One, published with the King’s privilege, available from the composer in Rue St. Honoré, near the Church of Saint-Roch.’

The preceding pages contain two prints of exceeding beauty, designed by Flemish printer Cornelis Vermeulen after paintings by Pierre Mignard, soon-to-be principal royal painter and director of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture as well as a manufacture that provided tapestries for the court. The first print is an allegory of Music, depicted as a pensive woman with a kithara in her left hand and a pen in her right, with which she is making revisions in a scroll of manuscript paper spread across her knees. She is sitting on a globe, symbolising the Earth as the foundation of the universe that resounds with the Pythagorean harmony of the spheres. A chirping nightingale is flying above her head, and four winged putti are making music at her feet. One is singing, while the others are playing the violin, the transverse flute, and the positive organ. These naked lads are probably about to swap instruments or invite more musicians to their company, since a lute is placed upside down next to the violin player, while a gamba is leaning against the organ next to the flautist. A two-manual harpsichord features prominently on the left. Its lid is closed, and there is a book of manuscript paper on its music desk.

The frontispiece comprises d’Anglebert portrait – an unprecedented concept in the then printing practice. With time, it increased the value of this unusual, intentionally exclusive publication, which (though no doubt expensive) paradoxically proved much sought after thanks to the idea of combining the composer’s image with the music in his print.

As to d’Anglebert himself, little is known of his musical education and the first three decades of his life. Baptised on 1 April 1629, he was the son of a well-to-do shoemaker from Bar-le-Duc. He left his hometown for the capital at an unknown date. By the time of his marriage in 1659, he was already a bourgeois de Paris and a long-time organist at the Jacobin church in Rue St. Honoré. His career really took off a year later, when he became a court harpsichordist to Philippe I, Duke of Orléans. How d’Anglebert bore with the duke’s excesses, his affairs with numerous male favourites and rows with his wife Henrietta – we do not know, but he persevered in the duke’s service for eight years. As early as 1662, he obtained an analogous post at the court of Louis XIV, in rather peculiar circumstances, since he actually bought the position from Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, the forefather of the French harpsichord school. The king’s ensemble consisted of eight singers, a harpsichordist and theorbo player, two lutenists, three gambists, four flautists, and four violinists. They performed during such social functions as royal suppers and balls, as well as the king’s coucher (retiring) ceremony. Under the reign of Louis XIV, the ensemble included the most famous musicians of the age, such as the composer Michel Richard Delalande, the gambist Marin Marais, the flautist Jacques Hotteterre, harpsichordists Jacques Champion de Chambonnières and François Couperin, as well as the master par excellence and opera composer nonpareil, Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Photo: Karol Sokołowski

We would quite likely know rather less about the Sun King court’s life and habits, had it not been for the Elector Palatine’s change of mind concerning the marriage of his eldest daughter Elizabeth Charlotte. The sympathies of Charles I Louis, of the house of Wittelsbach, turned towards France and decided to marry his Liselotte (as she was called from childhood) not to her cousin William of Orange-Nassau, as originally planned, but to the freshly widowed Philippe I, Duke of Orléans and younger brother of Louis XIV. The Princess Palatine was nineteen at the time of her proxy marriage. She first met her husband four days later, on 20 November 1671.

Many years later Liselotte would write rather unfavourably about Philippe I to her aristocratic confidante, probably from the perspective of her marital experience. He was not ugly, she admitted, but very short and sporting a huge nose. His mouth was too small, his teeth – bad, his manners – more like those of a woman than a man. He despised horses and hunting. Essentially his only interests were dancing, parties, social life, food, and sophisticated clothing. She concluded, on a sad note, that Philippe had most likely never loved anyone in his life.

She was probably wrong in this instance. The Duke of Orléans’ greatest love was apparently his namesake the Chevalier de Lorraine, ‘as beautiful as an angel’, who had become his partner already during Philippe’s first marriage to Henrietta. The latter was so jealous that, when she died aged less than twenty-six in mysterious circumstances (reportedly from an opium overdose), both gentlemen were suspected of murdering the duchess, who stood in the way of their romance. As to Liselotte, she did not care so much about her husband’s male favourites, but her life with the duke can hardly be considered a happy one. This did not stop the couple from fulfilling their marital obligations – thrice in fact, since after giving birth to two sons and her only daughter, Liselotte refused to share her bed with Philippe. For the rest of her life, filled as it was with courtly intrigue and personal worries, she sought solace in books, reading everything from the Greek classics to mathematical treatises. She was also extremely prolific as a letter writer.

It was Liselotte who in 1682, before falling out of favour with Louis XIV, described the famous jours d’appartement in a letter to her sister-in-law. Held by the monarch at Versailles every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, this entertainment started at six sharp in the afternoon, when the courtiers gathered in the king’s antechambers, and the ladies-in-waiting – in the queen’s chamber. For four hours, guests would dance, play cards, eat, drink, and listen to the musicians of la chambre du Roy. Those who got tired of dancing in the largest hall adjacent to the Sun King’s chamber moved on to other rooms. Apart from gaming tables and desks groaning with fruit or exquisite preserves, each room revealed new musical wonders. Solo pieces, trios, suites, arias, cantatas and operatic fragments were performed in the royal chambers: ‘Were I to proceed now, Madam, and tell you how splendidly furnished these rooms are and how much silverware has been collected there – ah, I would never be able to finish.’

Photo: Paweł Stelmach

The harpsichordist who performed on these occasions, Jean-Henry d’Anglebert, was, as we know, well familiar to the duchess. Highly valued as a teacher, he was entrusted with the task of educating another member of the Sun King’s family, his beloved illegitimate daughter Maria Anna de Bourbon, known as ‘Mademoiselle de Blois’. Famed for her beauty, she proved highly gifted as a harpsichord player. It was to her, already as ‘Princesse de Conty’ (Princess of Conti), that d’Anglebert dedicated his Pièces de clavecin. Three of the four suites in that collection open with unmeasured preludes that draw on the tradition of brief lute improvisations, mainly meant to test the instrument. The preludes, distinctly inspired by Frescobaldi’s and Froberger’s toccatas, introduce the key of each respective suite. They are followed by the main sequence of dance numbers (allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue), some of which return several times (Pièces en sol majeur, for instance, features as many as four courantes, marked by the composer as Courante, Double de la Courante, 2e Courante, and 3e Courante).

Though d’Anglebert himself did not live long enough to enjoy the success of his collection (he died in 1691), in the early eighteenth century it became a veritable bible of keyboard virtuosi and composers, including Johann Sebastian Bach, who learned from it the art of ornamentation. Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Pièces de clavecin would have been impossible without d’Anglebert suites. Copies of the 1689 edition have survived in a surprising number of libraries and private archives. Most importantly for us today, interest in d’Anglebert harpsichord masterpieces is steadily growing among context-conscious performers, who conjure up for their audiences the images of the jours d’appartement at Versailles. We can imagine the crowds of courtiers and gaming tables for chess, backgammon, and piquet, covered with green gold-fringed velvet. The king is dancing and having a good time. What Liselotte, Madam Palatine could hardly contain in her letters can still be heard in d’Anglebert glorious music.

Translated by Tomasz Zymer