One does not live on Wagner alone. But a lack of any coherent policy of familiarising the Polish audiences with his oeuvre is harder to stomach. Probably no European country – including Italy, which has a rather peculiar Wagnerian tradition – stages and presents his works as infrequently as we do. True, The Flying Dutchman or Tannhäuser will occasionally make an appearance on stage. Or there will be a few performances of Parsifal here and there. After a hiatus of nearly half a century since the premiere of the abridged version in Poznań, Warsaw will tackle Tristan: I’m not sure why, for the 2016 Teatr Wielki-Polish National Opera production was a disaster in every way.

We had only one production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg after the war, at Poznań’s Teatr Wielki, a production that was all right at best. Der Ring des Nibelungen was staged in Poland twice after 1945: in the late 1980s in Warsaw and twenty years ago in Wrocław. The three conductors responsible for the musical side of these ventures – Gabriel Chmura in the case of Die Meistersinger, and Robert Satanowski and Ewa Michnik, who prepared the Warsaw and Wrocław Rings, respectively – deserve praise for their persistence in pursuing ambitious dreams, especially in such unfavourable conditions. Yet these were in many ways too ambitious dreams.

Meanwhile, the 150th anniversary of the premiere of the entire Ring at the Bayreuth Festival is approaching and the entire music world has been preparing for it for a long time. In Poland the anniversary will go unnoticed, in contrast to the celebrations currently being prepared beyond our Western border (which is rather obvious), but also in the Czech Republic, where Wagnerians will be able to encounter the Tetralogy at least twice, including in a new staging by Sláva Daubnerová, planned for the three stages of Prague’s National Theatre. Incidentally, the sets for this show – produced in stages, beginning with the premiere of Das Rheingold in February 2026 – will be designed by Boris Kudlička, the new director of Teatr Wielki-Polish National Opera as of next season, and the costumes by Dorota Karolczak, a Bydgoszcz-born artist who for years has been working almost exclusively abroad (I wrote about her excellent designs for the Rodrigo production at the Göttingen Handel Festival six years ago).

Thus, lovers of Wagner’s oeuvre have no choice but to travel all over Europe in search of gems that will never be experienced in Poland by at least another generation of music lovers. Yet I went to Copenhagen for Die Meistersinger full of apprehension – after the musically disappointing and very unevenly cast premiere of Laurent Pelly’s staging at Teatro Real, co-produced with Den Kongelige Opera and Národní divadlo in Brno. I knew the Madrid production only from a broadcast. Visually, I liked it a lot, but I was completely unconvinced by Pablo Heras Casado’s interpretation: shallow, at times downright boring and entirely devoid of expression.

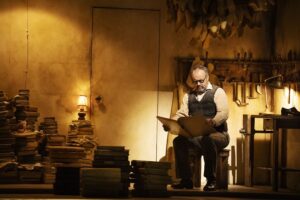

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg in Copenhagen. Johan Reuter (Hans Sachs). Photo: Miklos Szabo

In this case, however, the man behind the conductor’s desk was Axel Kober, a seasoned Wagnerian, who roused the Copenhagen Opera’s well-prepared orchestra from the very first bars of the overture, conducted lightly, in lively but not rushed tempi, with just the right dose of necessary pathos, though without an ounce of the grotesque. I was stunned with delight when I heard the chorus’ singing: meaty, dynamically nuanced, impeccable in its intonation, with perfectly delivered and evidently thought-out text. And then it got even better – Kober’s mastery was evident not only in the way he revealed the characters of the various protagonists, but also in his wise highlighting of the score’s contrasts: between farce and tragedy, monologues alternating between tenderness and hatred, a texture beautifully rarefied in love duets and dense as a silkworm weave in the stunning travesty of Bach polyphony in the finale of Act II.

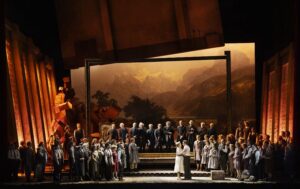

Die Meistersinger is a masterpiece of “mature style”, an opera full of contradictions and interpretive pitfalls, which both the conductor and the creative team managed to avoid. Laurent Pelly directed the whole in very sparse and beautifully symbolic sets designed by Caroline Ginet, with costumes designed by himself and Jean-Jacques Delmotte. The action takes place in a unified space defined by several monumental platforms and vertical panels that alternately create an illusion of St. Catherine’s Church, the night sky above the tangled streets of Nuremberg and the expansive meadows on the River Pegnitz in Franconian Switzerland. The rest is told by the few props: a gilded frame in which the obsolescent Meistersingers crowd around as if in an old-fashioned portrait; or a canvas with a colourful mountain landscape painting that ominously fades and falls in the finale, like a harbinger of an impending disaster. There are more similar harbingers in this staging. Pelly moved the narrative to the turn of the twentieth century, the time before the First World War, but wove into it signals of later evils. The cardboard houses from which the set designer built the medieval Nuremberg, and which the crowd reduces to ashes at the end of Act II, appear in Act III as a pile of rubbish, pressed deep into the idyllic scenery. When Beckmesser sneaks into Sachs’ workshop, he unexpectedly freezes at the sight of a bundle of shoes hanging from the ceiling, which bring to some spectators’ minds irresistible associations with the ghastly display at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

All this, however, reaches the audience as if through a fog, barely suggested by a subtle change of light, defused by bursts of laughter in brilliantly enacted farcical scenes. What attracts attention from the very beginning is the intricate portrayal of Beckmesser, who is transformed from a frustrated scoundrel into a wretched victim – of the crowd’s taunts, David’s aggression, Sachs’ ruthlessness. The credit for this goes not only to the director, but also to the conductor and the highly intelligent singer (Tom Erik Lie), who with his serenade in Act II makes the audience laugh uncontrollably, but when he sings “Morgen ich leuchte” at the tournament, the laughter gets stuck in our throats, and later, when, as the composer intended, he rushes stealthily into the crowd, we feel the bitter taste of shame in our mouths.

Only now have I realised that I start my assessment of the cast from Beckmesser, but I think this was the first time I saw a living, imperfect human being on stage, rather than a grotesque figure of an aging suitor. Another broken character is Sachs, whose final speech begins to resound with chilling tones – all the more emphatically as Johan Reuter’s magnificent, golden-hued bass-baritone seems to be singing about something else entirely. The Danish artist created one of the most memorable portrayals I had ever seen: with a voice that is not large, but masterfully controlled, with an incredible sense of the words and the content they carry. At this point I should start a litany of praises for all the singers, perfectly cast in their roles. May I be forgiven for mentioning only the magnificent portrayal of Eva by the luminous lyric soprano Jessica Muirhead; the uncommonly convincing, also with the beauty of his ardent youthful tenor, Jacob Skov Andersen (David); the mezzo-soprano Hanne Fischer, touching with the warmth of her voice, in the role of Magdalena; and Jens-Erik Aasbø, unobvious, more fragile and lost than impressive with the power of authority, in the bass part of Veit Pogner. Slightly less impressive was Magnus Vigilius, whose Jugendlicherheldentenor is healthy and beautiful in timbre, but not very flexible – although I still believe that the Danish singer is among the top ten performers of the role of Walther in the world.

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Finale. Photo: Miklos Szabo

Aware that I needed to stock up on my Wagner experiences, the following day I set off for Prague to see Siegfried, that is another preview of next year’s tour with the entire Ring des Nibelungen on period instruments, conducted by Kent Nagano. I have already written about this for Tygodnik Powszechny, although without going into details that are relevant to the current report. Firstly, the presentation of the individual parts of the Tetralogy begins in the Czech capital, which is not without reason the only Central European city on the itinerary of the Dresdner Festspielorchester and Concerto Köln, and to which the Ring found its way less than a decade after its premiere in 1876. Secondly, the “Ring historisch informiert” project is not just about reconstructing the historic line-up of the orchestra. It is a massive, long-term undertaking, featuring musicologists, theatre historians, linguists and anthropologists. Its aim is to recreate not only the original sound of the Tetralogy, but also its cultural context: the text delivery practice of the day, the way dramaturgy was shaped and the concept of musical time, in keeping with the spirit of the era.

As we can easily guess, from the very beginning the project had as many enthusiasts as fierce opponents – especially among admirers of stentorian, supposedly Wagnerian voices. Admittedly, listening to recordings of the previous instalments of the “historical” Ring, I, too, had doubts, especially about the Walküre cast, in my opinion too “characteristic”, not matching the level of expectations of the composer, who sought his dream protagonists among the most skilful performers of roles from the operas of Rossini, Donizetti and Meyerbeer. However, I have been a devotee of Kent Nagano’s conducting since the beginning of my career as a music critic. He was the one who won me over to Bruckner’s symphonic music – with interpretations that lightened the convoluted texture of these works and freed them from the dictates of the musical “barbarism” so beloved by other conductors. He was the one who amazed me with the versatility of his talent, thanks to which he interprets the scores of Beethoven and Brahms as insightfully as those of Messiaen and contemporary composers.

I was, therefore, not surprised that the main protagonist of the Prague concert performance of Siegfried at the State Opera was the orchestra – by no means homogeneous despite its expanded line-up, highlighting the sonic peculiarities of individual groups, sometimes even individual instruments. From the dense orchestral mass there began to emerge not only leitmotifs, but also less obvious elements of Wagner’s musical rhetoric: broad phrasing, discreet glissandi, strongly accented portamenti. In the quintet the violas, speaking in an almost human voice, finally came to the fore; the winds resounded with the rustle of leaves and the croaking of forest creatures, the percussion – with the whistles and murmurs of the relentless elements. The whole thing acquired quite a different colour – due to a lower pitch, different design and construction of the instruments, and, as a result, details of articulation.

Siegfried in Prague. Christian Elsner (Mime) and Thomas Blondelle (Siegfried). Photo: Václav Hodina

Audiences are slowly becoming accustomed to period instrument performances of nineteenth-century instrumental music; however, attempts to reconstruct the vocal practices of the day still provoke resistance, also in the context of the operatic form. This concerns particularly the so-called Wagnerian singing, which, for all intents and purposes, is an anachronistic construct, developed decades after the composer’s death, partly through a misinterpretation of his original intentions. Wagner wanted a specific timbre and expression, bringing to mind the sound of a natural spoken voice – combined with a technique that today is associated almost exclusively with Italian and French Romantic opera. Above all, the composer required his singers to be able to “tell a story” with music, to build a role in line with the principles observed by theatre actors of the day.

This is where the participants in the Dresdner Musikfestspiele project started and this is what Nagano himself mentioned, emphasising how difficult it was to find singers talented enough, yet willing to give up their desire for showmanship and devote many months to interpreting the text, mastering and integrating old acting techniques with vocal practice. It is, therefore, hardly surprising that the project features lesser-known artists, often taking their first steps in performing Wagner’s works. This is the first ever such a large-scale experiment. The musicians, including the conductor, are learning also from their mistakes. I have the impression that in Siegfried they have finally come close to their desired goal. This is evidenced by, for example, the fact that the title role was entrusted to Thomas Blondelle, who has a voice that is not very large, but well placed and attractive in timbre – which, combined with a thoughtful interpretation of his character, enabled him to play Siegfried in line with the letter of both the libretto and the score: as a precocious, yet naïve and at times cruel teenager who is desperately struggling with a crisis of adolescence.

Siegfried. Christian Elsner, Thomas Blondelle, and the boy soprano from the Tölzer Knabenchor (Woodbird). Photo: Václav Hodina

In Act III Blondelle found an excellent partner in Åsa Jäger, a youthful Brunhilde whose sparkling soprano has a powerful but generally skilfully controlled volume. The Nibelung brothers – Christian Elsner as Mime and Daniel Schmutzhard as Alberich – fully trusted the score and did not try to emphasise the moral ugliness of their characters by means typical of character singing. In this way, in spite of the still cultivated performance practice, they created ambiguous characters, marked by a clear tragic note. It was an excellent idea – and in keeping with the conventions of the period – to place Fafner way upstage and give him with a metal tube, as a result of which the dragon’s voice sounded all the more cavernous and ominous (Hanno Müller-Brachmann came out onto the proscenium only for the giant’s last, dying phrases, sung in his natural voice, as if to mark the loss of his magical power). It is a pity that the excellent boy soprano from the Tölzer Knabenchor (Woodbird) was not mentioned by name. I was slightly disappointed only by Gerhild Romberger (Erda), whose mezzo-soprano lacked the richness of tone and contralto depth necessary for the part, but who made up for this somewhat with her excellent acting.

The most magnificent performance of the evening, however, came from Derek Welton. Since the last time I heard him in the role of the Wanderer, his voice has acquired nobility and authority, but what served him well above all was the lowering of the orchestra’s pitch to the original version. The Australian singer is more comfortable in the lower range of his robust and juicy bass-baritone, which used to be associated with a rarefied timbre on the upper notes of this rather high part. This time, under Nagano’s watchful baton, Welton achieved perfection – I had not encountered such a musical interpretation of the Wanderer, well thought-out, derived directly from the text and backed by an impeccable vocal technique, for a long time.

I expect a similar experience, perhaps even more intense, next season – not only in Prague and Copenhagen, but wherever Wagner’s oeuvre continues to be the subject of admiration, inquiry and endless polemics. Fortunately, I like travelling.

Translated by: Anna Kijak