It all started on Yom Kippur – a day of atonement, forgiveness and reconciliation. The Germans gathered thousands of Jews from Kiev and the surrounding regions. They ordered them to report at a designated assembly-point with their valuables, money and a supply of warm clothes for a long journey. From there they started herding them in groups of a hundred towards a ravine called Babi Yar, overgrown with a thicket of alders and birches, running in a zig-zag between the settlements of Syrets and Lukyanovka on the outskirts of Kiev. It had once served as a campsite for soldiers, later becoming a burial ground. The ravine’s Jewish cemetery was officially closed in 1937. At the time there were already rumours that the NKVD used Babi Yar for burying victims of Stalin’s purges. Beneath the ground corpses were mounting, above ground the ravine was turning into a wasteland.

Yet its jaws had never devoured as many corpses as during the days between 29th September and 3rd October 1941. The Jews were stripped bare, laid down in rows among fallen leaves and shot in the back of the head; one group of ten after another, amid shouts from drunken SS men and Ukrainian policemen attempting to deafen with vodka any remnants of sensitivity. During five days of uninterrupted slaughter 33,771 people were murdered. At least these are the numbers that feature in German reports. However, the executions continued right up to the Red Army’s liberation of Kiev. For two years from the memorable feast day of Yom Kippur, Babi Yar continued to function as a concentration camp for communists, prisoners of war and partisans, where Jews, Poles, Ukrainians and Sinti and Roma Gypsies were shot. At least 70,000 people died in this overgrown ravine. With news of an imminent Russian counter-offensive, the Germans ordered prisoners to dig up the corpses and burn them on grates in the open air. After the war the entire terrain was cordoned off so that victims of Stalin’s murders would not be unearthed. Then the site was turned into a park. The first memorials to the slaughter of Jews at Babi Yar were only erected after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The execution site at Babi Yar. Photo: Yad Vashem Archives.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko already complained about their lack in 1961 in his poem Babi Yar, which opens with words that over the ravine there are no memorials – only a steep landslide akin to a crude tombstone. The poem appeared in the Literaturnaya Gazeta heralding the first signs of a literary thaw in the wake of Stalin’s death – on par with Solzhenitsyn’s novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Shostakovich’s imagination was moved to the core; he had originally intended to compose a piece, a type of a symphonic poem with solo bass, based on this work. Later, however, he came across another verse by Yevtushenko and changed his whole concept. In less than two months he composed four more movements – including one to texts specially commissioned from the poet – and enclosed the entire piece in a form reminiscent to a symphonic cantata rather than a choral symphony. In the composer’s list of works it features however as Symphony No. 13 in B-flat Major, op.113 subtitled ‘Babi Yar’ for bass or bass-baritone, bass choir and orchestra.

The first movement Adagio Babi Yar, the longest and most dramatic, calls to mind references to the tone painting present in the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (1934) that was banned by Stalin. In the Mahlerian Scherzo Humour – witty and sardonic to the extreme – Shostakovich also alludes to Bartok’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion in a gesture of sweet revenge for mocking his Leningrad Symphony in Concerto for Orchestra. The next Adagio, In the Store, takes on the form of an almost liturgical lament commemorating the hardships endured by women during the Great Patriotic War. The Largo Fears, set to verse commissioned by the composer, describes events of the Soviet repression in an exceptionally complicated musical language, which makes references to both his Symphony No.4 and later attempts of combining the tonal system with elements of serialism. The final Allegretto Career is a type of an artistic self-examination – maintained in a semi-ironic and grotesque tone with numerous references to Symphony No.3 and quartets from the turn of the 1940s.

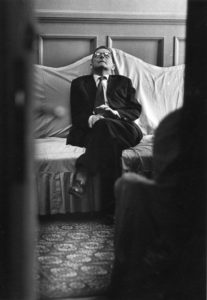

Shostakovich in 1961. Photo: Vsevolod Tarasevich.

Shostakovich completed work on the symphony on 20th July 1962, the day of his release from the hospital in Leningrad. On the evening of the same day he took a night train to Kiev in order to present the score to Boris Gmyrya, a retired soloist of the city’s opera whom he had chosen for the solo part. From there he returned to Leningrad for a meeting with Yevgeny Mravinsky, who was to conduct the work’s premiere. That was when all the trouble began.

In the spring Yevtushenko had given in to a wave of massed criticism regarding his work. He introduced significant changes to his poem Babi Yar, in some instances completely altering their tone (the phrase ‘I feel like a Jew wandering across ancient Egypt’ was altered to ‘I stand at the source that gives me faith in brotherhood’). Gmyrya withdrew from the project as a result of pressure from the local Communist Party committee. Mravinsky followed in his footsteps – albeit later claiming that he withdrew for purely personal reasons, which decision put an end to his long friendship with Shostakovich.

In the end, the work’s premiere was conducted by Kiril Kondrashin, with the Moscow Philharmonic, the Gnesin Institute Choir and Vitaly Gromadsky as soloist (18th December 1962). All did not go smoothly. In the last moment the TV broadcast was cancelled. Party dignitaries did not turn up for the work’s premiere. Nevertheless, the concert took place to a full hall and finished to a rousing ovation. Sadly the thaw had come to an end. After the next few performances, despite the introduction of successive changes to the text, Symphony No.13 was banned from performance in the USSR. It met with similar difficulties in other countries of the Eastern Bloc. Not until the fall of the great Red Bear was it once again included in the repertoires of great orchestras.

Translated by: Anna Kaspszyk