A Parable of Resurrection

Resuscitation often ends in the patient being seriously battered and bruised. The sternum breaks, the ribs crack, blood pours into the pleura – a scary list, but no one doubts that inept resuscitation is better than no resuscitation. If it had not been for a musical passion of a lecturer from the University of Göttingen, perhaps Handel’s operas would not have emerged from obscurity. Oskar Hagen, an art historian and amateur musician, became interested in the oeuvre of the Halle master during a long illness. Naturally, he shared his fascination with his wife, the singer Thyra Leisner, and a friend who was a cellist. Everything began with home concerts, fashionable in university circles at the time. Encouraged by their success, Hagen decided to organise something on a larger scale. He produced an edition of Rodelinda and organised the first modern performance of the opera – on 26 June 1920, with a cast featuring university students and lecturers accompanied by musicians of the Akademische Orchestervereinigung conducted by him. These were the beginnings of Händel-Festspiele Göttingen, a cradle of Handel revival, which reached the British Isles only in the 1950s.

There would have been no revival, however, if Hagen hand not adapted Handel’s operatic legacy to the sensitivity of the listeners, brought up for generations on Wagner’s works. He cut the scores of his idol into pieces, rearranged them for a large orchestra, “embellished” the recitatives with instrumental interludes, removed repetitions from da capo arias, transposed the parts written for castratos an octave down and entrusted them to low male voices. This does not change the fact, however, that before the outbreak of the Second World War nineteen Handel operas were revived by German theatres, with no fewer than nine being presented in Göttingen (among them Radamisto, Ottone and Giulio Cesare). In 1943–1953 – with an interval of two years caused by a conflict with the Nazi authorities – music directorship of Händel-Festspiele Göttingen was in the hands of the conductor Fritz Lehmann, an ardent advocate of early music and founder of Berliner Mottetenchor. Since 1981 the Festival has been ruled by British apostles of historical performance: respectively, John Eliot Gardiner, Nicholas McGegan, and since 2011 – Laurence Cummings together with the Managing Director Tobias Wolff.

Fllur Wyn (Esilena) and Erica Eloff (Rodrigo). Photo: Alciro Theodoro da Silva

This season I had an opportunity to come to Göttingen for a longer visit, and I decided to use it and visit the Händel-Festspiele. Unfortunately, I missed a concert performance, apparently excellent, of the oratorio Saul, featuring soloists, NDR Chorus and FestspielOchester conducted by Cummings. I arrived in Göttingen three days later, in time for the auditions of the Festival competition, featuring just five ensembles from Germany, Holland and Switzerland. They were all excellent, which makes it all the more difficult to bridle at the verdict of the jury, which included the Baroque violinist Anne Röhrig, the flautist Maurice Steger and the countertenor Kai Wessel. My sympathies were with the Dutch ensemble Dialogo Antico, not only because of its excellent programme (vocal-instrumental works by Handel, Stradella, Alessandro Scarlatti, Bononcini and Arvo Pärt), but also because of the mature and focused interpretations by the countertenor Toshiharu Nakajima. But the winner was Ensemble Caladrius from Germany, with its charismatic flautist Sophia Schambeck, who displayed undoubted virtuosity in a much more accessible repertoire. It is a pity, though, that all three prizes – Main Prize, Bärenreiter Urtext Prize and the Audience Prize – went to one ensemble. The other finalists deserved at least some kind of consolation prize.

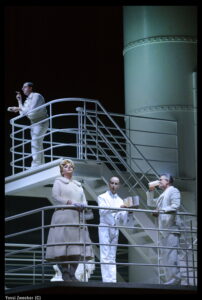

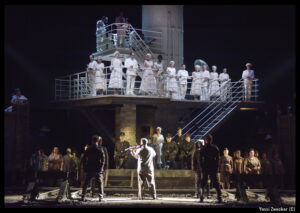

The remaining Festival events were focused on the annual opera premiere at the Deutsches Theater, a Neo-Renaissance building from 1890, which in the mid-twentieth century was eventually transformed into a Sprechtheaterhaus. Since then the building has been resounding with music only once a year, during the Händel-Festspiele. This year it was the turn of Rodrigo, Handel’s first Italian opera, loosely based on the story of Roderic, the last Visigothic king, defeated by the Arabs at the Battle of Jerez de la Frontera. Loosely, because the main theme of the work, the initial title of which was Vincer se stesso è la maggior vittoria, is an inner transformation of the protagonist, who after yet another marital infidelity matures and returns to his beloved although infertile wife Esilena. In between we have everything a Baroque opera should have – desire for revenge, unexpected exchange of partners and several dead bodies. Huge support for the intelligent and occasionally very witty direction by Walter Sutcliffe – who turned Rodrigo into a contemporary warlord battling some shady characters somewhere on the frontier of Western civilisation – was provided by Dorota Karolczak’s sets, perfectly laid out and vividly conveying the labyrinth of nooks and crannies of a dilapidated palace. Interestingly, the sets had been made in the workshops of Poznań’s Teatr Wielki, which should quickly start collaborating with Karolczak directly – as this will be beneficial to the company’s own productions. A separate round of applause is also due to the team of MaskenWerkstatt Schweiz, who so suggestively made up Erica Eloff singing the title role that some audience members could swear they were watching a countertenor.

Almira’s Songbook – Seconda Prat!ca, Queen’s Minstrels. Photo: Alciro Theodoro da Silva

Eloff, who was excellent in portraying her character, was not quite up to the requirements of the role, however – splendid in lyrical fragments, she was disappointing in arias requiring truly masculine bravura and vocal glamour typical of the art of the castratos. Anna Dennis (Florinda) in turn, a singer with a powerful, dark soprano, sometimes made up for technical shortcomings with a large volume. It was a big mistake to cast Evanco as a countertenor. Russell Harcourt fought bravely but unsuccessfully – this is not surprising, because it is a typical en travesti role, written for an agile female soprano with easy top notes. Among the other cast members worthy of note were, especially, Fflur Wyn, a technically phenomenal Esilena, captivating with her golden-hued voice, and Jorge Navarro Colorado (Giuliano), excellent as an actor and singing with a secure and clear tenor. However, the unquestionable hero of the evening – as well as several other Festival events – was the FestspielOrchester conducted by Laurence Cummings. This was yet another piece evidence showing how much can be done by skill, knowledge and passion combined with complete trust in the Kapellmeister. The Göttingen Festival Orchestra features members of Les Arts Florissants, Concerto Köln, Complesso Barocco and other premier league ensembles. Cummings gained his experience as the boss of the London Handel Orchestra and co-founder of the London Handel Players. Their music-making brims with pure joy and authentic, mature love for the legacy of the Festival’s patron.

All these qualities shone even more brightly during a gala concert at St. James’ Church, featuring the French countertenor Christophe Dumaux, whose career has been evolving along quite unexpected lines. Most artists singing falsetto on operatic stages are stars of a few seasons, singers with lovely but harmonically not very rich voices, quickly paling beside fuller, well-handled female voices. Yet Dumaux has been maturing like good wine. He skilfully passes from register to register, sounding like a proper haute-contre at the bottom and shining like a dramatic soprano at the top. He makes a brilliant use of messa di voce, embellishes his arias stylishly and tastefully, and phenomenally builds tension in da capo arias. I will remember his “Ah, stigie larve” as an unrivalled model of the Handelian mad scene; his “Pompe vane di morte” finally convinced me of the greatness of Rodelinda. Dumaux said goodbye to the audience with just one encore: “Cor ingrato” from Rinaldo. I had not returned from a concert so hungry for more for quite some time.

Franziska Fleischanderl (salterio). Photo: Alciro Theodoro da Silva

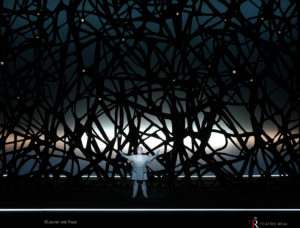

The remaining Festival events did not carry as much weight for me, which does not mean that they were disappointing. The flautist Dorothea Oberlinger’s recital with Cummings on the harpsichord should serve as an example of how to compile a virtuoso programme of Baroque music with less sophisticated listeners in mind. The performance by the Seconda Prat!ca ensemble, which decided to present a musical portrait of Almira, the protagonist of Handel’s first opera, captivated the listeners with the sensual beauty of Iberian vocal music. The soloists and Coro e Orchestra Ghisleri conducted by Giulio Prandi made up for technical shortcomings with so much enthusiasm that we greeted their performance of Handel’s Dixit Dominus with thunderous applause without any hesitation. Nor did we hesitate before getting up before dawn to get to a concert at 5am and hear how Franziska Fleischanderl welcomes the sun with the delicate sound of the salterio and stories of her extraordinary instrument.

Next year Händel-Festspiele Göttingen will celebrate its centenary. History will come full circle – the organisers are planning a new staging of Rodelinda, from which everything began. It will be interesting to see whether one day they will come up with the idea of reconstructing it in the form devised by Oskar Hagen. Who broke Handel’s ribs, left him badly bruised, but resurrected his oeuvre for good. For the benefit of the whole world.

Translated by: Anna Kijak