Setting out on my journey back from Basel to Warsaw, I stopped in a little square in front of the hotel, lured by the sight of a glass-fronted cabinet with needless books. I expected to find there some easy read for the long journey with a change in Frankfurt; instead, much to my surprise I took off the shelf an edition of Sławomir Mrożek’s Ucieczka na południe (Escape to the South) – slightly yellowed, but otherwise untouched by time. Fate writes the best libretti for my operatic journeys. A severe winter approaches and I’m coming back from an escape to the south, to a city only five degrees of latitude farther north, where I will again try to find something that would free me from “a feeling of emptiness”. It would be interesting to see whether in six months, when I set off as usual on a tour of niche festivals, I’ll come across an abandoned copy of Mrożek’s Maleńkie lato (Little Summer).

What makes all this even more bizarre is the fact that I went to Basel – a city on the Rhine, between Switzerland, Germany and France – to see Il ritono d’Ulisse in patria. A production adapted and directed by Krystian Lada, delayed like Odysseus’ return – the March premiere was wiped out by the previous wave of the pandemic. An original vision of a supposedly flawed opera, Monteverdi’s “ugly duckling”, which hatches laboriously out of a great confusion of styles and only in the course of the narrative does it begin to reveal clearly contrasted emotions and moods, and, above all, wonderful portrayals of the two main characters. I had been dying of curiosity since spring, because Lada decided to remove the figure of Ulisse from the original structure, admitting openly that he intended to draw the audience into a performance, a “participatory project” based on Monteverdi’s work, presented deliberately not on the vast state of the Opera House, but in the adjacent Schauspielhaus. Lada replaced the eponymous King of Ithaca with a collective protagonist, a figure of alienness, an archetype filtered through the experience of reading Joyce, Hauptmann and Kazantzakis, reflected in the mirror of contemporary problems of refugees and migrants. He brought on stage eight “men of Basel”, strangers blending in with the local community. The musical portrait of Ulisse was replaced with their silence, snatches of utterances, body languages, electronics discreetly linking the various episodes.

Katarina Bradić (Penelope). Photo: Judith Schlosser

What makes Lada different from most young opera directors today is the fact that, having taken a work apart, he is able to put it together again – sometimes into a surprising whole, but without losing or spoiling anything along the way. It seems to me that in the pre-premiere talks he put too much emphasis on the idea of staging a “Ulisse without Ulisse”. The biggest asset of his concept is his masterful highlighting of a narrative element that has been there in Il Ritorno from the very beginning and is often missed by both directors and performers. The incredible convergence of dramaturgical patterns in Monteverdi’s operas and Shakespeare’s late plays has been pointed out by John Eliot Gardiner, among others. It is incredible, because it is highly unlikely that Monteverdi ever encountered Shakespeare’s oeuvre. Yet the works of the two men mirror each other, as if by some kind of cultural convergence: the tension in them stems from the contrast of quickly alternating tragic and ironic scenes triggering tears of laughter and sincere emotion. Lada condensed the opera’s three acts into an uninterrupted action, roughly two hours long, directed like an operatic Tempest or Winter’s Tale, fast flowing, coherent and engaging. And although his adaptation went very far – which he did not hide from the very beginning – he did not do any harm to Monteverdi, and at times even helped the myth by giving it a more human form. The poignant finale, in which Penelope cries “Or si, ti riconosco” at the sight of each of the eight strangers, makes me think of an alternative version of the myth, relegated to oblivion for millennia, in which the queen, consumed by longing and broken by loneliness, gives herself to all the suitors one by one.

The Basel production is full of other tropes and perfectly enacted episodes, which show that Lada understands the mechanism of the operatic form, that he knows how myth works, and that he is able to relate all this to the present – without falling into literality and banality. Having a limited number of singers at his disposal, he gives each of them several roles – not always in accordance with the traditional performance practice, following above all the logic of a focused narrative. Thus Penelope is also Human Frailty, the gods are transformed into suitors, the allegories of Time, Fortune and Love act as links between the earth and Olympus. The director offers us an Epicurean interpretation of the myth of the great journey and even greater longing. The beautiful, imperious, self-absorbed gods decide to play humans and fail in their confrontation with humanity: mortal, flawed and yet stubbornly seeking happiness that comes even if only from the absence of suffering. The most moving character is Eumete, naive four-eyes in overalls, ready to help all the Odysseuses of this world. His opposite is Iro – burning with hatred and aiming a knapsack sprayer at the strangers as if they were bedbugs. The central figure in the narrative is Penelope, an indomitable woman, faithful not only to her lost husband, but also to herself. Her love for Ulisse gives her strength and teaches her compassion. It helps her satisfy her own body, refuse love to the usurpers and give it to those who really needed it.

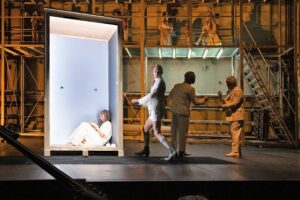

Katarina Bradić, Théo Imart (Giunone/Anfinomo/L’Amore), Alex Rosen (Nettuno/Antinoo/Il Tempo) and Rolf Romei (Giove/Pisandro/La Fortuna). Photo: Judith Schlosser

Drawing a preliminary sketch of characters on an open stage, before the first sounds of the music are heard is slowly beginning to become a distinctive feature of Lada’s productions. Radiant, elaborately coiffed gods, covering up deficiencies of their looks with grotesque jockstraps and corsets (excellent costumes by Bente Rolandsdotter), silently circulate among props, aiming from a bow at a man-shaped target signed with the name of Ulisse. In between their archery displays, they step onto the proscenium and gesticulate vigorously. Only after a while does the audience, snuggling down in their seats, realise that the deities control the traffic in the auditorium. Then with equal relish they “pull” the instrumentalists into the orchestra pit and give the signal for the story to begin.

The constant twists and turns of the narrative are accompanied by seamless changes of scenery (Didzis Jaunzems), consisting of a few simple ladders, boxes, scaffoldings and platforms, precisely controlled by the technical staff, the extras and the singers. The minimalistic nature of the sets focuses the audience’s attention all the more effectively on the psychology of the protagonists and the multifaceted story, which reaches its dramatic climax in the scene of the suitors’ trial. Penelope stands in the dust of the earth like a true shaman, covered by a dirty, decaying cloak of her lost husband, raising a bow made of deer antlers above her head. Disguised as humans, the deities lose their power before they so much as touch Odysseus’ weapon. They bow before a mortal woman, the most faithful of the faithful, the strongest of the strong, the most tender of the tender. They leave humiliated, retreating before the nameless wanderers who, by the end, will mingle with the audience, reveal their identities and complicated stories, and find their home in Ithaca. The myth comes full circle and, at the same time, clashes with reality. After an absence of twenty years Ulysses returns in a completely different form.

“Men of Basel”. Photo: Judith Schlosser

Basel is one of the bastions of the historical performance movement, so there is nothing surprising about the technical proficiency and sense of Monteverdian style of the members of the I Musici de la Cetra ensemble, prepared by Johannes Keller and Joan Boronat Sanz. However, I did not expect that this modest, experimental production would provide me with so many vocal thrills. The expected star of the evening was Katarina Bradić as Penelope, whom I had heard four years earlier in the same role in Brussels under René Jacobs’ baton. Not only has Bradić’s contralto grown in brilliance and density in all registers since then, but Lada also uses the singer’s acting potential to the full – my heart went up to my throat already in the opening lament “L’aspettato non giunge”. The real revelation, however, was Ronan Caillet as Eumete: the French tenor, a pupil of Christoph Prégardien, impresses with his extraordinary musicality, handsome voice with a slightly baritonal tinge, and excellent acting skills. It is impossible to ignore the talent of Théo Imart, a young male soprano who played Giunone, Anfinomo and L’Amore – another living proof that the time of “disembodied” countertenors is fortunately coming to an end, with their place being taken by singers with flexible, colourful and expressive voices. Equally promising is the presence of Jamez McCorkie in the cast. Not so long ago the Basel Telemaco sang baritone roles: he has recently changed his Fach to tenor, retaining a brassy brilliance in the lower register and a quasi-soul articulation, remarkably consistent with his “black” voice. Among the other soloists, special mention should be made of Rolf Romei (Giove/Pisandro/La Fortuna) – a Basel Opera veteran, and expressive spinto tenor normally associated with quite a different repertoire; and the actor Martin Hug, who created a brilliant and vocally surprisingly competent portrayal of the pathetic Iro.

This is the kind of theatre – insightful, economical, daring – I naively dreamt of when the Polish opera world was entering the dark night of the pandemic. Perhaps I will see it one day. With this hope I returned north, to a country, where “sometimes it was so boring that the local dignitaries, having carefully drawn the curtains, would put on fake paper noses in front of their mirrors just to amuse themselves a little”.

Translated by: Anna Kijak