Czemu nie w chórze?

Ten esej – który zamówił u mnie Tomasz Bęben, dyrektor naczelny Filharmonii Łódzkiej im. Artura Rubinsteina – ukaże się wkrótce w księdze pamiątkowej, pięknie wydanej w ramach obchodów jubileuszu półwiecza tamtejszego chóru. Wszyscy już nie możemy się doczekać, także autor innego z zamieszczonych w niej tekstów, odwieczny Upiorny przyjaciel, mentor i towarzysz wielu operowych wędrówek Rafał Augustyn. Pandemia nikogo i niczego nie oszczędza. Odbiera nam zdrowie i spokój, krzyżuje plany muzyków, instytucji i wiernych słuchaczy. Na pocieszenie został nam jeszcze internet, do którego – z konieczności, ale i na szczęście – przeniosła się znaczna część życia muzycznego, nie tylko w Polsce. W przeddzień kolejnej transmisji z Filharmonii Łódzkiej, która w Święto Niepodległości nada o 19.00 recital Tymoteusza Biesa z utworami Chopina i Szymanowskiego, proponuję w sumie optymistyczną lekturę. Słuchajmy. Zbierajmy się w chóry, choćby maleńkie, i śpiewajmy, choćby wirtualnie. Jeszcze się przyda. Jeszcze się odrodzi, nawet jeśli muzyczna wiosna przypadnie na całkiem inną porę roku. Otuchy!

***

Uwielbiam Norwida i wielokrotnie stawałam w obronie jego pamięci. Niech więc będzie mi wybaczone, że tytuł eseju wzięłam z Norwidowskiego wiersza, który zaczyna się tak: „Śpiewają wciąż wybrani / U żłobu, gdzie jest Bóg; / Lecz milczą zadyszani, / Wbiegając w próg…”. Wprawdzie wydźwięk tej poezji jest odrobinę inny, nasuwa jednak na myśl refleksje, dlaczego w chórze śpiewają wybrani, czy zawsze tak było, czemu ten śpiew służył przez wieki i jak to właściwie się zaczęło.

Zgodnie z zaproponowaną przez Darwina teorią doboru płciowego śpiew ptaków wynika z potrzeby podtrzymania gatunku: pomaga wytyczyć granice rewiru, przywabić partnera i odstraszyć potencjalnych rywali. Najświeższe badania wskazują jednak, że nawet ptaki dążą do zestrojenia działań w tym naturalnym celu. Wszystkie zwierzęta – nas nie wyłączając – komunikują się w bardzo złożony sposób. Ludzka mowa zyskuje na sile wyrazu, jeśli poprzeć ją sugestywną koordynacją wzorców rytmicznych i melodycznych oraz dostosowaniem tempa, brzmienia i barwy głosu do charakteru przekazu. Naukowcy odkryli, że ptaki z gatunku strzyżów rdzawogrzbietych (Campylorhynchus rufinucha) znacznie skuteczniej porozumiewają się w większych grupach, twórczo reagując na zgrane duety innych zanoszących miłosne trele par w pobliżu. Młode osobniki wsłuchują się pilnie w śpiew doświadczonych amantów i uczą na własnych błędach – najmniejsze widoki na udany związek mają strzyże, których głos przepadnie w tym chórze bądź naruszy skomplikowaną ptasią harmonię.

Analizując historię śpiewu chóralnego w kulturze zachodniej można przeprowadzić pewną analogię do ptasich duetów, i to na kilku poziomach: jako dialog między jednostką a wspólnotą, między sacrum a profanum, między tekstem a muzyką, między głosem ludzkim a dźwiękiem instrumentów. W występach antycznego chóru taniec, śpiew i muzyka tworzyły nierozerwalną całość. Żaden z tych elementów nie miał prawa oddzielnego bytu. Tadeusz Zieliński nazywał ją „trójjedyną choreją”, wywiedzioną ze specyficznej melodii samego języka, ekspresywności każdej wypowiedzianej frazy i muzyczności wszelkich działań choreutów, których kroki, ruchy i gesty składały się w precyzyjny, abstrakcyjny kod – przekazywany z pokolenia na pokolenie, czytelny dla widza na podobnej zasadzie, na jakiej po dziś dzień interpretuje się środki ekspresji japońskiego teatru nō albo hinduskiego kathakali. Kilkunasto-, czasem nawet kilkudziesięcioosobowy chór pełnił rolę czegoś w rodzaju aktora zbiorowego. Grecki czasownik „khoreuo” znaczył pierwotnie tyle, co „być członkiem chóru”. A to już znaczyło bardzo wiele: nie tylko tańczyć i śpiewać, ale też czynić wspólnotę, zajmować się czymś żarliwie, szukać w chorei partnera – niczym w rozświergotanym, budzącym się do życia wiosennym lesie.

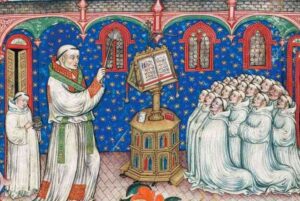

Girolamo da Milano, zwany Maestro Olivetano, Chór mnichów śpiewających oficjum. Graduał z klasztoru benedyktynów Santa Maria di Baggio, ok. 1439-47

Zadziwiające, ale więcej wiadomo – choćby z literatury – jak funkcjonowały śpiewające wspólnoty w czasach antycznych niż w średniowieczu. Chóralistykę tej długiej epoki w dziejach Zachodu możemy rozpatrywać wyłącznie przez pryzmat praktyki liturgicznej – która i tak była znacznie bogatsza i bardziej zróżnicowana, niż można by wnosić na podstawie XIX-wiecznej kodyfikacji chorału, dokonanej przez mnichów z kongregacji Solesmes. Korzenie tak zwanego chorału gregoriańskiego sięgają czasów Cesarstwa Zachodniego, gdzie mniej więcej w IV wieku doszło do wymieszania tradycji grecko-łacińskiej z żydowską tradycją Świątyni Jerozolimskiej. U sedna śpiewu chorałowego znów leżał dialog: Wschodu z Zachodem, dziedzictwa starożytności z ówczesną teraźniejszością. Brytyjska tradycja chóralna, słusznie uważana za najstarszą ciągłą kulturę muzyczną Europy, liczy ponad tysiąc czterysta lat i też bynajmniej nie jest jednorodna. Jej początków można się doszukać już w VI wieku, w czasach chrystianizacji Wysp podjętej z inicjatywy papieża Grzegorza Wielkiego; przede wszystkim zaś w działalności św. Augustyna, pierwszego arcybiskupa Canterbury. Augustyn nawracał pogan tyleż łagodnie, co konsekwentnie – słowem i przykładem do naśladowania – co okazało się prawdziwym przełomem w dziejach Kościoła rzymskiego. Po sukcesie jego misji z Rzymu na Wyspy zaczęli przybywać śpiewacy kościelni, przygotowujący neofitów do wykonawstwa chorału i świadomego uczestnictwa w liturgii. W 602 roku Augustyn ufundował w Canterbury katedrę pod wezwaniem Najświętszego Zbawiciela, wcześniej zaś szkołę, w której uczono chłopców łaciny i muzyki. Takie były początki angielskich chórów katedralnych, których do dziś funkcjonuje kilkadziesiąt, a słynna King’s School w Canterbury, założona w 597 roku, jest prawdopodobnie najstarszą szkołą na świecie.

Rozważając rzecz od tej strony, najistotniejszą przemianą, jaka z punktu widzenia chóralistyki dokonała się w wiekach średnich, był wynalazek wielogłosu – rozumianego zresztą całkiem inaczej niż dziś. Zaczęło się od heterofonii, przedziwnej we współczesnych uszach faktury, wynikającej z połączenia melodii głównej z improwizacją. Taki śpiew miał charakter głęboko wewnętrzny: prowadzony pierwotnie w unisonie, stopniowo włączał doń elementy wyrażające stan duchowy oraz indywidualność wykonawców. W IX wieku dał początek formie organum, w której głos główny uzupełniano głosami równoległymi, prowadzonymi w „doskonałych” interwałach oktawy, kwinty, kwarty i prymy. W XI stuleciu wykształciło się organum swobodne, wykorzystujące nie tylko paralelizm głosów, lecz także ich ruch boczny (ze stałym tenorem), przeciwny oraz prosty – czyli zmierzający w tym samym kierunku, lecz w innych interwałach. Forma osiągnęła swój szczyt w wieku XII – w organum melizmatycznym, w którym melodia chorałowa przeistoczyła się w pochód długich dźwięków, kontrapunktowany wyższym głosem organalnym, idącym naprzód w szerokich, zdobnych melizmatach. Usamodzielnienie się poszczególnych głosów i pojawienie się całkiem nowej organizacji rytmicznej dały początek „prawdziwej” polifonii – uniezależnionym od liturgii motetom z wielogłosową fakturą, wykorzystującym świeckie teksty i melodie; odwołującym się do struktury motetów i zwrotkowych konduktów mszom, na czele z powstałą około 1360 roku Mszą Notre Dame Guillaume’a de Machaut, pierwszą „autorską” aranżacją katolickiego ordinarium missae. Dodajmy do tego typowo brytyjskie innowacje, między innymi charakterystyczny cantus gemellus, czyli gymel, oparty na pochodach akordów tercjowych, oraz English discant, charakteryzujący się tercsekstową strukturą akordów, a zyskamy obraz sytuacji wskazujący na coraz tłumniejszy udział śpiewaków w muzycznym dziele podtrzymania ludzkiego gatunku.

Ale dopiero w XVI wieku chóry rozbłysły pełnią brzmienia, jaką znamy do dziś. Nadciągał zmierzch wszechwładnego chorału, świtała epoka polifonii kościelnej, wymagającej dobrze postawionych i nieskazitelnych technicznie wysokich głosów. To właśnie wówczas wykształcił się podstawowy układ SATB. Etymologia większości nazw głosów sięga głębiej, do początków średniowiecznej polifonii, kiedy do pojedynczej linii chorałowej śpiewanej w wydłużonych wartościach i dlatego zwanej tenorem (od łacińskiego tenere, „trzymać”), dołączył głos wyższy (superius). Z pierwotnego organum prowadzonego w równoległych kwartach i kwintach dwugłos wyewoluował w znacznie bardziej wyrafinowany discantus (w wolnym tłumaczeniu „śpiew oddzielny”), w którym głos wyższy, prowadzony zazwyczaj w ruchu przeciwnym, „przeciwstawiał się” tenorowi w prostym kontrapunkcie nota contra notam („nuta przeciw nucie”). Później dołączył do nich głos trzeci, śpiewający mniej więcej w tym samym rejestrze, co tenor, ale niejako „przeciw” niemu, i dlatego nazwany z łacińska kontratenorem (contratenor). Co ciekawe, angielska nazwa sopranu chłopięcego (treble) wywodzi się od zniekształconego triplum, które oznaczało zarówno organum trzygłosowe, jak i najwyższy głos w takiej polifonii; tymczasem polska, przestarzała nazwa takiego sopranu (dyszkant) nawiązuje do samej techniki discantus. W miarę dalszego rozwoju wielogłosowości pojawiły się dwie odmiany kontratenoru – contratenor altus („wysoki”, prowadzony nad linią tenorową) i contratenor bassus („niski”, prowadzony pod tenorem). Stąd już tylko dwa kroki do stosowanych we współczesnej chóralistyce określeń sopran/alt/tenor/bas, gdzie włoski termin soprano (od sopra, „ponad”) zastąpił wcześniejsze superius i cantus, bo i tak nazywano odrębną melodię prowadzoną w głosie najwyższym.

Thomas Webster, Chór wiejski, 1847. Victoria and Albert Museum w Londynie

W dobie renesansu pozycja muzyki systematycznie rosła, wzmacniana przez humanistów, którzy stawiali ją na równi z poezją albo prozą. Na sposobach układania mowy dźwięków – poza fascynacją antykiem – zaważyły też tradycje kulturowe, religia oraz doświadczenia historyczne poszczególnych regionów. Pierwociny nowego stylu chóralnego nietrudno wytropić w utworach mistrzów szkoły franko-flamandzkiej, przede wszystkim Orlanda di Lasso, jednego z najpłodniejszych i najwszechstronniejszych muzyków w dziejach. Jego motety, psalmy i lamentacje aż kipią od emocji – podkreślanych wyrafinowanymi zabiegami fakturalnymi, idealnym sprzężeniem słowa z melodią i użyciem śmiałych chromatyzmów. Niemcy – posłuszni luterańskiej koncepcji muzyki jako ładu zorganizowanego i uporządkowanego przez Boga – wychodzili od skrupulatnej analizy i próby zdefiniowania tekstu, a dopiero potem brali się za wznoszenie stosownej budowli muzycznej. Angielska muzyka kościelna epoki Tudorów powstawała w trudnej epoce konfliktów na tle religijnym: kompozytorzy godzili wodę z ogniem, przeplatając elementy nowego obrządku z tradycją katolicką. Wtedy właśnie zaczęły powstawać typowo wyspiarskie formy chóralne, m.in. anthem, angielski odpowiednik motetu albo kantaty, wtedy też ukształtowało się charakterystyczne brzmienie tamtejszych zespołów: z mocno zaakcentowanym udziałem sopranów chłopięcych, zestawionych z kontratenorami, tenorami i basami.

Prawdziwa ekspansja chóralistyki zaczęła się jednak dopiero w epoce baroku – wraz z jej stopniowym wkraczaniem w domenę muzyki świeckiej. Dzięki upowszechnieniu niedrogich wydawnictw nutowych obyczaj wspólnego śpiewania upowszechnił się w domach mieszczaństwa. Publiczne sale koncertowe rosły jak grzyby po deszczu. Rozkwitło życie festiwalowe: najstarsza tego rodzaju impreza na świecie, Three Choirs Festival, organizowany na przemian w katedrach w Gloucester, Worcester i Hereford, odbył się po raz pierwszy w 1715 roku. Z czasem rozrósł się z lokalnego mityngu muzyków kościelnych do masowego święta z udziałem najwybitniejszych wykonawców występujących w coraz to szerszym repertuarze, przede wszystkim oratoryjnym.

Kolejny zwrot dokonał się w dobie rewolucji francuskiej, kiedy muzyka chóralna zyskała całkiem nowe znaczenie polityczne: stała się zwielokrotnionym głosem wspólnoty, wyznacznikiem tożsamości, skuteczną zachętą do buntu i walki. Piątą rocznicę zburzenia Bastylii celebrowano z udziałem kilkutysięcznego tłumu śpiewaków. Zaczęły powstawać chóry przy armiach, pierwsze chóry robotnicze, pierwsze zespoły żeńskie. Śladem „orfeonów”, czyli zainicjowanych przez francuskiego kompozytora i filantropa Wilhema sociétés orphéoniques, poszły towarzystwa śpiewacze organizowane niemal w całej Europie: w Niemczech, Szwajcarii, na Wyspach Brytyjskich. Na ziemiach polskich największą popularnością cieszył się ruch cecyliański, nawiązujący do przedrewolucyjnej jeszcze tradycji Cäcilien-Bündnis, założonego w 1725 roku w Wiedniu przez Antonia Caldarę. Pierwsze towarzystwo cecyliańskie we Lwowie powstało w 1826 roku, z pomysłu „Wolfganga Amadeusza Mozarta juniora” – bo tak przedstawił się lwowianom Franciszek Ksawery, najmłodszy syn wiedeńskiego klasyka. Choć tożsamość po rozbiorach najżarliwiej kultywowały chóry wielkopolskie, za apogeum ruchów śpiewaczych uchodzi zlot z okazji odsłonięcia Pomnika Grunwaldzkiego w Krakowie, 15 lipca 1910 roku, kiedy sześciuset chórzystów z trzech zaborów wykonało Rotę Feliksa Nowowiejskiego pod kierunkiem kompozytora. Po II wojnie światowej niemal w każdym zakątku kraju wyrastały chóry moniuszkowskie. W większości państw europejskich poziom profesjonalnych zespołów filharmonicznych i operowych jest wprost proporcjonalny do poziomu amatorskiej chóralistyki wspólnotowej.

Chór szkoły przygotowawczej Lambrook w Winkfield w angielskim hrabstwie Berkshire, połowa lat 60. XX wieku

Śpiewanie w zgodnym i dobrze skoordynowanym chórze wyzwala hormony szczęścia, odpowiedzialne zarówno za zdrowie psychiczne, jak i fizyczne. Uwalnia dopaminę, neuroprzekaźnik kontrolujący prawidłową koordynację ruchową i napięcie mięśni, wspomagający pamięć i prawidłowe procesy poznawcze. Stymuluje wydzielanie kortyzolu, który umożliwia skuteczną walkę ze stresem. Powoduje wyrzut oksytocyny do krwi –hormonu sterującego naszym życiem emocjonalnym. Muzykowanie w ludzkim chórze tym się różni od rozgwaru ptaków w wiosennym lesie, że polega na budowaniu dojrzałej relacji z większą liczbą partnerów: zasłuchanych w siebie i w dzieło współwykonawców, kształtujących swoją muzyczną wrażliwość odbiorców. „Śpiewajcież, w chór zebrani!” – powtórzę znów za Norwidem. Piskląt będzie z tego mnóstwo.