Hell Was Shut Off and Heaven Was Opened

The hated lockdown has never been associated in Poland with what it should be associated with – a tool for fighting the pandemic in a comprehensive manner based on Erasmus’ principle that prevention is better than cure. A tool requiring integrity and consistency from governments, insight and humility in the face of the unknown from experts, and ethical sensibility, solidarity and empathy from societies. The restrictions – annoying and incomprehensible to most Poles – have proved ineffective for a variety of reasons. Instead of giving us hope, they have left us believing that they undermine our freedom, that they become an element of a ruthless political fight, that they – and not the disease – lead to thousands of human tragedies and unprecedented crisis of our healthcare system.

Above all, however, they have destroyed in us the vestiges of our already underdeveloped communal thinking – a prerequisite of survival, thanks to which the United Kingdom is now exiting from a lockdown no one in Poland can even imagine. It emerges from lockdown not only healthier and more prudent, but also equipped with a range of skills developed in the most difficult moments of isolation. I’ve been watching the Brits’ musical initiatives from the beginning of the pandemic – with growing admiration. Culture in the British Isles has not frozen even for a moment: it has simply become locked in people’s homes, connecting with the world by means of modern technology, which makes it possible not only to stay in touch with the audience, but also to continue earlier projects and make constructive plans for the future.

The fruits of such painstaking preparations include the first, still virtual, Easter Festival of the Oxford Bach Soloists – an ensemble founded in 2015 by Tom Hammond-Davies and from the very beginning operating as a musical community, bringing together renowned singers and orchestral musicians, students, amateurs, educators as well as scholars representing a variety of disciplines, from history and theology to literature studies and philology. The ensemble and its boss have set a rather extraordinary goal for themselves: to present Johann Sebastian Bach’s entire vocal legacy in chronological order and in combination with the context and purpose of each work. They have planned the venture for twelve years – who knows, the seemingly lost year of the great pandemic may have equipped them with interesting tools which might be used successfully in future seasons.

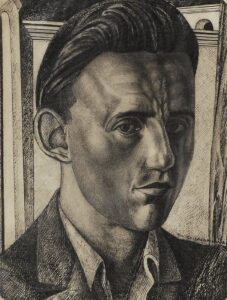

Tom Hammond-Davies. Photo: Nick Rutter

The programme of this year’s festival featured Cantatas BWV 4 and BWV 31 as well as the Easter Oratorio. Yet for a variety of reasons I will focus on St John Passion, a masterpiece which for some time has been winning back the performers and listeners by storm. Hans-Georg Gadamer writes in The Relevance of the Beautiful that the phenomenon of Passion music ranges “from the highest claims of artistic, historical and musical culture to the openness of the simplest and most heartfelt human needs”. It is indeed a communal phenomenon: it explains the meaning and purpose of suffering, teaches compassion, helps carry the burden of one’s fears and misfortunes. In their remarkable undertaking the Oxford Bach Soloists managed to fulfil all the conditions detailed by Gadamer and elevate St John Passion to the rank of a powerful metaphor for the current crisis.

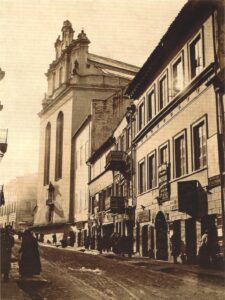

Both of Bach’s surviving Passions date from his late period, after he became cantor at Leipzig’s St Thomas’ Church in 1723. His predecessor there was Johannes Kuhnau, an organist and music theorist, composer of a Passion According to St. Mark which had been performed alternately during Good Friday Vespers at St. Thomas’ and St. Nicholas’ in Leipzig since 1721. As he was writing his St John Passion, Bach expected it to be performed in his own church, yet as the practice observed in Leipzig would have it, the premiere of the new passion was to take place at St Nicholas’ Church. The misunderstanding came to light just four days before the event. At the last minute the cantor had to bring together a huge vocal-instrumental ensemble featuring musicians from both churches: his new piece was larger than any previous cantatas and the Magnificat, his first significant composition for Leipzig’s main churches. Despite these perturbations Bach’s St John Passion was heard in its original version on 7 April 1724. The starting point for the libretto was the Gospel of John, to which were added individuals verses from, among others, the Brockes Passion, a popular work at the time. The inconsistencies in the text later prompted Bach to introduce a number of modifications. This may be why St John Passion has been labelled an incomplete work, interrupted in the middle of its conception.

Just how undeserved the label is can be seen in the growing number of interpretations by the most distinguished specialists in historical performance. With their own experience of last year’s “St John Passion from isolation”, the Oxford Bach Soloists decided to add another dimension to their venture, inviting Thomas Guthrie to direct it. Guthrie, an English director, singer and actor, has for years been fascinated by the idea of staging a musical work not only through a dialogue between the artists and the audience, but also in terms of communal experience – being part of the narrative of the work, experienced bodily and sensually by the performers.

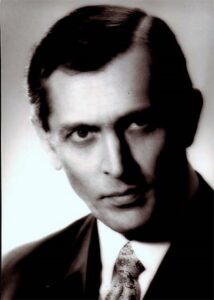

Nick Pritchard as the Evangelist. Photo: Helena Cooke

Guthrie the director is like an honest and ingenuous child: he knows that miracles happen in the theatre and he knows how to convince his audience of that. In 2017 I experienced this first-hand during a performance of The Magic Flute in Longborough, when he stepped into the role of performance creator to such an extent that he directed an unexpected technical break in the first act, addressing the audience as if they were a bunch of overgrown nursery school kids: much to those kids’ delight. Guthrie once compared the expression of singers to the cry of an infant who would not rest until it had conveyed its weighty message to all those present. I didn’t expect, however, that in St John Passion inside Oxford’s Christ Church Guthrie would look at the drama of Jesus, his judges, disciples and torturers through the eyes of a precocious child who understands more from this tragedy than many adults.

This was already felt in the opening chorus “Herr, unser Herrscher”, based on musical and rhetorical antitheses and making us realise the paradox of Jesus’ glory and humiliation. In his staging Guthrie plays with literally every gesture, colour and prop. Wherever in the music we have earth and the temporal world, the image sparkles with bright colours. When Bach transports us to Heaven, Guthrie paints it using pastel, even unreal hues. Christ’s Passion is black and white, shrouded in a grey mist of pain. The masterful camerawork brings to mind associations with old painting, in which artists smuggled elements of their own world into the biblical landscape. In Guthrie’s staging our rightful companions in the Way of the Cross include microphones on sliding tripods, flashing camera lights, clothes abandoned in the aisle and instrument cases.

Peter Harvey (Christ) and Hugh Cutting.

The director was just as meticulous in making sure that there would be inner tension between all the participants in the dramatic action, from the main characters to the individual orchestral musicians (needless to say, all involved in the performance fully respected the rules of physical distancing). The Oxford Passion is equally an open allegory and a deeply lived experience of community – with the narrated story, with the other performers, with oneself. This is hugely thanks to Nick Pritchard as the Evangelist – sung with a light and superbly articulated tenor, beautifully open in the upper register – who supported his vocal artistry with excellent acting, creating an unforgettable portrayal of a fragile, often helpless witness to a tragedy, overwhelmed with despair. Just as memorable was Peter Harvey’s Christ: subdued, bitter, fearful in the face of impending death. I think that some shortage of volume in his beautiful and technically assured voice worked fine in such a concept of the role. Alex Ashworth was a movingly human, dithering Pilate, singing with a baritone that was robust, agile and spot-on when it came intonation. Worthy of note among the other soloists were Lucy Cox with her luminous, truly joyful soprano (a riveting “Ich folge dir gleichfalls mit freudigen Schritten”), the countertenor Hugh Cutting, whose rendition of “Von den Stricken meiner Sünden” sent shivers down my spine, and, especially, the velvety-voiced Ben Davies, who impressed with his cultured singing and extraordinary sensitivity in the bass arioso “Betrachte, meine Seel, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen” from the scourging scene.

When it comes to the singing of the chorus I was impressed above all by their understanding of the text, delivered with ardour, pain and compassion, and at the same time exemplary voice projection and a touch of individuality, which I value highly in performances of Baroque music. In the instrumental ensemble every musician was in a class of his or her own. I am also full of admiration for the elegance and effectiveness of the conducting of Tom Hammond-Davies, who directed the whole performance in the rather difficult acoustic conditions of Christ Church, with the musicians placed rather untypically and widely apart at times.

I keep thinking about this Passion and constantly hope to hear it live one day performed by these artists in Guthrie’s staging: simple, economical, painfully thought-provoking. Is it really necessary to die so many times in order to finally rise from the dead? Hasn’t there been enough of this suffering?

Translated by: Anna Kijak