Pocieszenie w samotności

Z dnia na dzień coraz dobitniej się przekonuję, jak trudno kogoś pocieszyć. Wyjdzie człowiek z fałszywego założenia, że to niewiedza rodzi lęk, podrzuci garść pożytecznych informacji – i wzbudzi jeszcze większą panikę. Uprzedzi, że trzeba ćwiczyć pokorę i cierpliwość, bo zanosi się na dłuższą przerwę od koncertów i spektakli – oskarżą go o defetyzm. Spróbuje przekonać, że najgorsze już za nami – padnie ofiarą wyznawców spiskowych teorii dziejów. A gdyby tak Państwa rozbawić? Może to przynajmniej się uda. Co jakiś czas będę sięgać do archiwum Mus Triton i podrzucać mysie komentarze do archiwaliów. Tym razem sprzed lat siedemdziesięciu. Oby nie tak wyglądało nasze życie muzyczne po pandemii.

***

Był taki prorok, który wiedział, że nikt nie jest prorokiem we własnym kraju. Doszedł do tego smutnego wniosku prawie dwa tysiące lat temu i od tamtej pory nic się nie zmieniło. No, prawie nic. Już nie trzeba być prorokiem, by wiedzieć, że nikt nie jest prorokiem we własnym kraju. A już zwłaszcza na prowincji. Świadczą o tym zapiski Z pamiętnika młodego dyrygenta, zamieszczone w numerze 2/1960 „Ruchu Muzycznego”. Oto notka opatrzona datą 2 września:

Dzisiaj – jak to się mówi – objąłem swoje pierwsze w życiu kierownicze stanowisko. I pomyśleć, że jeszcze przed trzema miesiącami byłem studentem, a dzisiaj jestem już odpowiedzialny za działalność artystyczną Wojewódzkiej Orkiestry Symfonicznej. Jak na początek – duży krok w tym, co nazywa się karierą. „Moja” orkiestra liczy ponad czterdzieści osób. Jutro mam pierwszą próbę. Dyrektor przyjął mnie uprzejmie, ale ze źle ukrywaną niechęcią. Nic dziwnego, przed rokiem z jego inicjatywy powstała orkiestra i myślał zapewne, że będzie jej udzielnym władcą. Ale Ministerstwo stwierdziło, że brak mu kwalifikacji dyrygenckich i musi nie tylko zrezygnować z ambicji artystycznych, lecz także dzielić się władzą. Obawiam się, że będzie zatruwał mi życie.

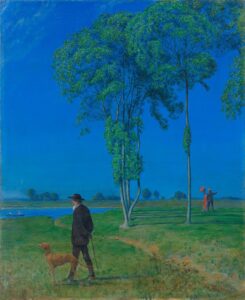

Hans Thoma: Samotność (1906). Ze zbiorów Landesbank Baden-Württemberg, Karlsruhe.

Już nazajutrz miało się okazać, że będąc młodym dyrygentem na rubieży, dostanie w kość przede wszystkim od swoich pracowników:

…drugi fagocista nic nie mówiąc wyszedł w trakcie próby. Na moje zapytanie inspektor oświadczył, że ten fagocista pracuje na pół etacie i obowiązuje go tylko pół próby! Fantastycznie! Za to na pełnym etacie pracuje w Wojewódzkiej Radzie Narodowej. A co najważniejsze – jest szwagrem wiceprzewodniczącego tejże Rady i dlatego nie można go ruszyć z żadnej posady.

Ciekawe, czyim szwagrem był oboista Filharmonii Łódzkiej i jak wyglądała struktura zatrudnienia w tamtejszej orkiestrze, skoro inny nasz dyrygent – starszy i nieco bardziej doświadczony Henryk Czyż – zwierzał się w te słowa Januszowi Cegielle po powrocie z Anglii, gdzie miał szczęście prowadzić słynną Hallé-Orchestra:

Znakomity poziom artystyczny i fantastyczne wprost kwalifikacje techniczne! O dyscyplinie, panującej w zespole powiedzieć mogę tylko tyle, że gdy w pewnym momencie oboista pomylił się na próbie, z a r u m i e n i ł się ze wstydu. Hej, łza się w oku kręci!…

Młody dyrygent zalał się gorzkimi łzami już po trzech tygodniach pracy z Wojewódzką Orkiestrą Symfoniczną:

Dziś zgłosił się pierwszy waltornista i zażądał podwyżki od 1 października. Zagroził, że jeśli jej nie dostanie, to odejdzie natychmiast. Ledwo go ułagodziłem obietnicami. Obserwuję, że od pewnego czasu stosunki w orkiestrze znacznie się popsuły. Raz po raz wybuchają sprzeczki między muzykami i to w czasie prób. Podejrzewam, że jest to robota dyrektora, który w ten sposób utrudnia mi pracę. Mnie osobiście trudno utrzymać porządek na próbach, ponieważ dotąd nie pracowałem z żadną orkiestrą i prawie każdy muzyk jest ode mnie o wiele starszy. Tzw. autorytet artystyczny niestety nie wystarcza dla zachowania dyscypliny.

Nie desperować, młodzieńcze, tylko się starzeć z godnością. Skoro Ministerstwo oddelegowało na wysuniętą placówkę, pewnie miało w tym jakiś cel. Nie ma co liczyć na uznanie w kraju, trzeba się jednak solidnie napracować, zanim pojawi się szansa prorokowania na obczyźnie. Czyżowi już się udało, choć początki były trudne:

Gdy w którymś miejscu IV Symfonii Brahmsa zaznaczyłem „poco crescendo” nieco zbyt „serdecznym, polskim” ruchem – odpowiedziało mi takie crescendo, że zimny pot mnie oblał z wrażenia. Z taką orkiestrą dyrygent nie musi być agitatorem, który wszelkimi dostępnymi mu środkami próbuje nakłonić zespół do pewnych poczynań interpretacyjnych – o wszystkim decyduje się tu samemu w sposób ostateczny i to z rygorem natychmiastowego wykonania. Bardzo to przyjemne poczuć się przy pulpicie dyrygenckim nie pedagogiem, ale koncertującym artystą…

Od razu widać, że Czyżowi się za tą rubieżą we łbie przewróciło. Żeby zostać artystą – nawet koncertującym – trzeba najpierw umrzeć. Przed śmiercią warto się jednak podszkolić w dziedzinie socjotechniki, co młody dyrygent zrozumiał już na początku listopada:

Po głębokim namyśle do najbliższego koncertu wstawiłem „Preludia” Liszta. Wiem, że orkiestra temu nie podoła, ale za to recenzenci i publiczność na pewno będą zadowoleni. (…) Było tak, jak przewidywałem. (…) Kierownik Wydziału Kultury przyszedł mi po koncercie gratulować w imieniu władz. Oświadczył, że teraz jest już spokojny o dalszy los orkiestry. Wykonanie „Preludiów” było – moim zdaniem – okropne.

Tak czy siak, nie samą sztuką człowiek żyje. Po godzinach trzeba się gdzieś podziać. Jak to wygląda na rubieży?

Byłem dzisiaj w kwaterunku. O mieszkaniach dla mnie i muzyków na razie głucho.

…a jak na obczyźnie?

Jestem zachwycony krajem, ludźmi i gościnnością. Moi gospodarze byli tak ujmujący, że zwrócili się do kilku studiujących w Anglii naukowców polskich z prośbą, aby każdy z nich poświęcił mi trochę czasu…

Wygląda na to, że proroków nie chcą przyjmować pod swoim dachem i we własnym, i w obcym kraju. Tyle że we własnym prorocy się tym martwią, w obcym zaś nie posiadają się ze szczęścia, co z pewnym zdumieniem konstatuje

MUS TRITON