“O Pangloss!” cried out Candide, “such horrid doings never entered thy imagination. Here is an end of the matter. I find myself, after all, obliged to renounce thy Optimism.” „Optimism,” said Cacambo, “what is that?” “Alas!” replied Candide, “it is the obstinacy of maintaining that everything is best when it is worst.” Volaire’s tale of Candide – an alleged bastard of Baron Thunder-ten-Tronckh’s sister, a good-natured simpleton who lived peacefully in a Westphalian castle until he rashly kissed Cunegonde, his host’s daughter, and was expelled – probably would not have seen the light of day, if everything had been going well in the world. From Voltaire’s point of view, the world was in dire straits. This was the time of the Seven Years’ War, which came to be regarded as the turning point in the Franco-British conflict over overseas domains. Europe was still unable to recover after the tragic earthquake in Lisbon, which took the lives of nearly 100,000 people. The aftershocks could be felt even as far as Venice, a fact recorded in his memoirs by no less a figure than Giacomo Casanova. Portugal’s capital was reduced to a heap of rubble, as was the doctrine of optimism based on the theodicy of Gottfried Leibniz, who did justice to God and concluded that we lived in the best of all possible worlds and if black thoughts overwhelmed us, it was only because we did not have God’s insight into everything. The final straw was the famous Lettre sur la Providence by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who in 1756 read Voltaire’s Poem on the Lisbon Disaster and “formed the mad project of making him turn his attention to himself, and of proving to him that everything was right”. The French philosopher lost patience. He decided to prove to Rousseau that his project was indeed mad. He got down to writing Candide and in January 1759 he published it simultaneously in five countries. The work, allegedly published to amuse the few witty readers, contains withering criticism of state structures and religious institutions of the day. Voltaire set his protagonist on a roguish journey across the worst of all possible worlds, in which survival was possible only thanks to a practical philosophy of common sense. Like in any other intricate satire, in Candide, too, the funnier it gets, the more terrible it gets. The naive youth eventually abandons his optimism and it is not quite clear what he chooses instead. It is probably the only book in the history of literature, with regard to which it is really hard to say whether it ends happily or not.

Candide fled as quickly as possible – the 1787 edition of Candide, illustrated by Jean-Michel Moreau.

The story has had numerous adaptations, including Candy (1958), a novel by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg, in which a naive female Candide finds herself in increasingly comic situations featuring a band of mad and oversexed men. It has inspired masters of black humour, anti-utopias and the Theatre of the Absurd. It also inspired Lillian Hellman – an American playwright and screenwriter, partner of Dashiell Hammett, the author of popular detective novels – who in 1950 appeared before the infamous House Committee on Un-American Activities. She refused to testify against her colleagues who sympathised with the Communist Party USA, as a result of which she was blacklisted in Hollywood, alongside such distinguished figures as Orson Welles, Dorothy Parker, Irwin Shaw and other stars of the Dream Factory. The trauma prompted her to make the English adaptation of Jean Anouilh’s play The Lark – a story of Joan of Arc with a happy ending. Leonard Bernstein wrote the incidental music and, encouraged by the success of the production on Broadway, persuaded Hellman to work with him on a “comic operetta” based on Voltaire’s novella. As the method employed in American theatres demanded, the project was carried out in a multifaceted fashion: Hellman created the book and the spoken dialogue, Bernstein composed without close collaboration with the author, sung parts were written by the so-called lyricists (including John Latouche, Dorothy Parker and Richard Wilbur), and the whole was orchestrated by Hershy Kay.

Candide was premiered in December 1956 at the Martin Beck Theatre on Broadway. It was directed by Tyrone Guthrie, co-founder of the famous Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Canada, who also had a background in opera. The conductor was Samuel Krachmalnick, Bernstein’s pupil from Tanglewood. Given Broadway standards, the production was a flop: there were “only” seventy-three performances in two months. The critics complained primarily about the gap between Berstein’s light, witty, pastiche-like music and the dead serious libretto by Hellman, who preferred to crush the demons of McCarthyism in her own way, rather than to create a perverse modern equivalent of a naive simpleton’s journeys. The production closed, but the music appealed to the audience, which continued to listen to a recording of the premiere for years. People hummed the “Venetian” waltz What’s the Use, in which a group of swindlers and extortionists complained about insufficient proceeds from their rascally activities; laughed out loud, listening to Dear Boy from the Lisbon episode, when Pangloss – Candide’s mentor – remains imperturbably optimistic despite catching syphilis from the beautiful maid Paquette; admired Glitter and Be Gay, an extremely difficult and extremely funny parody of the “jewel song” from Gounod’s Faust sung by Cunegonde, who settled surprisingly well into a life as a mistress of a Parisian cardinal and a Jewish merchant. Famous for its crazy changes of metre, the overture to Candide was conducted by the composer at a New York Philharmonic concert already in 1957 and within two years became part of the repertoire of nearly one hundred American orchestras, used as a dazzling concert opener, i.e. a work beginning the first part of the evening.

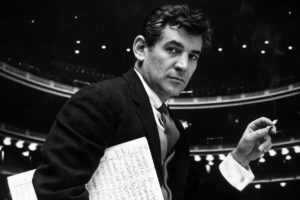

Leonard Bernstein, 1955. Photo: Getty Images.

Yet attempts to resurrect Candide on stage were not very successful. The first London production, in 1959, at the Saville Theatre, briefly transferred to Oxford and Manchester, ran for sixty performances. In the United States the work was presented several times in concert and there were two productions by minor theatre companies from Los Angeles. In the early 1970s Lillian Hellman, dejected, withdrew from the project and forbid any revivals featuring her original book. A new, one-act version was created by Hugh Wheeler – it contained additional lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, was shorted by nearly a half in comparison with the original and the orchestra was reduced to thirteen musicians. The staging (on several platforms to avoid set changes) was by Harold Prince, a seasoned director of popular musicals. The performances were conducted by John Mauceri, who went on to accompany all future metamorphoses of Candide. The premiere took place in 1973 at the Chelsea Theatre Centre in Brooklyn and was an instant hit. One year later the production found its way to Broadway, where it ran for over seven hundred performances over two seasons. Initially a somewhat heavy, overly didactic tale as presented by Hellman, Candide became just the opposite: it was transformed into mad tomfoolery, sending the spectators into successive paroxysms of laughter.

The soprano Beverly Sills, director of the New York City Opera, demanded that this musical amusement be expanded to truly operatic proportions. Before the 1982 premiere at the NYCO another two-act version was created, with added scenes by Wheeler and with restored numbers from the original version mixed incoherently to the detriment of not only the dramaturge of the whole but also of the music itself. Who knows what would have then happened to the piece, if it had not been for Mauceri, who, when preparing a new staging for the Scottish Opera (1988), rearranged the material and restored the right proportions between laughter and tears, joke and bitterness, emotion and grotesque. The final revision was done by Bernstein himself – two concerts of the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican Centre featured Christa Ludwig as the Old Lady and Nikolai Gedda as the Governor. A recording with the same cast released by Deutsche Grammophon sparked another wave of popularity of Candide, which has since been presented in dozens of productions across the world. It came to Poland in 2005 in a staging by Tomasz Konina for Teatr Wielki in Łódź conducted by Tadeusz Kozłowski.

The playbill for Candide at the Broadway Theatre, 1974.

In Voltaire’s novella, which, in a way, is a parody of a classic romance and a picaresque novel, the scenery and situations change in a kaleidoscopic sequence. The protagonists of Candide – and the readers with them – fall into the clutches of the Portuguese Inquisition, rush on horseback to Cádiz, sail across the Atlantic to Paraguay, find themselves in Eldorado, return to Europe, wander across the Ottoman Empire only to settle on a small farm on the banks of the Propontis. The protagonists of Bernstein’s work travel across the ocean of Europe’s musical tradition. There are as many references to Lehár, Viennese Strausses and Offenbach as there are allusions to Gilbert and Sullivan’s Victorian comic operas, works by Mozart and Smetana, Protestant chorales, klezmer music, Spanish flamenco, Czech polka and Scottish gigue. Any attempt to pigeonhole Bernstein’s Candide is doomed to failure. Is it a musical or an operetta? A singspiel or a comic opera? The director of the premiere, Tyrone Guthrie, once said, referring to the work that “Rossini and Cole Porter seemed to have been rearranging Götterdämmerung”. A compliment or an insult? Is Candide a masterpiece or a delicious prank of an otherwise excellent musician?

In the finale of the book the indefatigable Pangloss warns that grandeur “is very dangerous, if we believe the testimonies of almost all philosophers” and proceeds to list kings who were assassinated, hanged by the hair of their head, run through with darts and led into captivity. At some point Candide stops the litany with his famous pronouncement: “Neither need you tell me that we must take care of our garden.” Perhaps Bernstein did not aspire to grandeur either? Perhaps he preferred to take care of his garden? Whatever that means, for, as I have written earlier, the greatest minds have been wrangling over the meaning of the last words of Voltaire’s novella.

Translated by: Anna Kijak