Some say that Kirill Serebrennikov is a Meyerhold for our times. He is certainly the most recognisable dissident among Russian artists: after spending nearly two years under house arrest for allegedly embezzling public funds, after a truly Kafkaesque trial that ended with a fine, a three-year suspended prison sentence and a ban on leaving the country, and, finally, after losing his position as artistic director of the Gogol Centre, which he has turned into one of the world’s most vibrant centres of independent theatre in less than a decade.

Serebrennikov left for Berlin in March 2022, following a decision to overturn his sentence issued a month after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. He openly condemned the war started by his country already in May, when Tchaikovsky’s Wife was premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. In Russia some of his productions were immediately removed from the repertoire, while others had his name erased from them. Still, he has had more luck than Meyerhold, who was accused of collaborating with Japanese and British intelligence, tortured for months and executed in 1940. Both Meyerhold and Serebrennikov became involved in complicated deals with the government, althought it would be hard to call either of them an opportunist, at least in today’s sense of the word. And yet such attempts are made, also in Poland, where the process of erasing Russian culture has gone the farthest of all European countries (for reasons that are quite understandable). Attempts to explain the dramatic choices and complexities of the career pursued by Serebrennikov – a gay man who does not hide his orientation, the son of a Russian Jew and a Ukrainian woman of Moldovan descent, born in Rostov-on-Don, where in 1942, in the Snake Ravine near the city, the largest murder of Jews in the USSR’s wartime history was carried out – are viewed in some circles as a faux pas similar to trying to defend the princess from Rousseau’s Confessions for her dismissive attitude toward the hungry peasants.

Yet a comparison between Serebrennikov and Meyerhold is valid in many respects. The legendary reformer of Soviet theatre was also an extravagant rebel; he, too, shocked audiences, shattered conventions, drew on the most diverse styles of theatrical production. He demanded absolute commitment and incredible physical fitness from his actors. Meyerhold’s stagings aroused either admiration or fierce opposition: they left no one indifferent. The same is true of Serebrennikov, who some believe to be a brilliant visionary, while others regard him as an outrageously overrated director who continues to capitalise on his relatively recent persecution by the Putin regime.

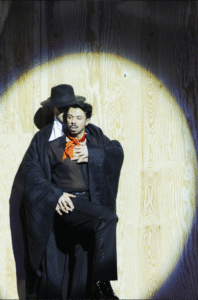

Hubert Zapiór (Don Giovanni). Photo: Frol Podlesnyi

What I find seductive in his theatre is the pure acting element as well as an ability – long forgotten in Poland or perhaps never highly regarded – to soften pathos with the grotesque, to relieve tension by means of irony and black humour. True, Serebrennikov’s stagings are generally overloaded with ideas, sometimes not very coherent, full of incomprehensible allusions and tropes leading nowhere. But even if they annoy, it is impossible to take your eyes off them and then to get rid of the reflections whirling in your head.

That is why I went to Berlin for the premiere of the last part of the so-called Da Ponte Trilogy, produced by Serebrennikov with the Komische Oper for over two years. I decided to miss the first two parts, because I had had enough of both Così fan tutte and The Marriage of Figaro for the moment. However, the story of the punished rake promised to be provocative even when compared with the director’s previous ventures. First of all, Serebrennikov announced the whole thing as Don Giovanni / Requiem, which smacked of Teodor Currentzis’ earlier Mozart experiments. Secondly, he decided to imbue the narrative of the opera with references to the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Thirdly – to replace Donna Elvira with a male victim of Don Giovanni’s conquests, Don Elviro, portrayed by the Brazillian sopranist Bruno de Sá.

It promised to be at least a beautiful catastrophe, but what did come out of it was a production thrilling with its pace, teeming alternately with horror and wit, interrupted again and again at the premiere by applause and bursts of laughter from the audience. Yes, it is another excessive production, drawing liberally on both Serebrennikov’s previous stagings (including, not surprisingly, that of Pushkin’s Little Tragedies, staged at the Gogol Centre when the director was already under house arrest) and “all the means used in other plays”, as in Meyerhold’s case. Once again, it is a production that leaves us with more questions than answers, unknown perhaps even to Serebrennikov himself. It contains the most recognisable elements of the Russian artist’s theatre – from dreams and ravings, the sometimes unobvious multiplication of characters, to disjointed narrative.

And yet it is watchable – probably because Serebrennikov, despite seemingly turning everything inside out, still highlights the most essential aspect of the title character’s story. It is not a story about promiscuity or obsession, it is a story about the mechanisms of power and its links to sex. Thus, the homoerotic subtext of the introduction of Don Elviro recedes into the background: the age, gender and orientation of the “victims” do not matter at all to Don Giovanni, just as they did not matter to Casanova, the greatest lover of all time. Yet Serebrennikov completes this spectacle of power with a surprising conclusion: that the descent into the hell of agony can give even a villain a chance and influence the fate of the world. Hence the reference to the Tibetan Book of the Dead and Jungian archetypes. Hence the idea to explain everything from the end and start the action already to the sounds of the overture, with a daring scene of Don Giovanni’s supposed resurrection at his own funeral.

Photo: Frol Podlesnyi

This is an arch-Russian scene, played out on several planes, with sets simpler than in Meyerhold’s productions, based on boxes of raw pinewood that perfectly organise the space (arranged in diverse configurations, they will stay with us until the end of the performance). A group of grotesque mourners bid farewell to the protagonist as if he were a Soviet dignitary. To kiss the deceased, they have to lean over the edge of the open coffin, sometimes climbing the steps to do so, then perform a suitable show of despair in front of the rest of the congregation. Meanwhile, in an adjacent box black-clad bodyguards (excellent choreography and stage movement by Evgeny Kulagin) are desperately struggling with the Commendatore’s corpse, trying to pack it into a black body bag. In the midst of this pandemonium Don Giovanni begins to show signs of life and, to the evident frustration of the mourning-faking participants in the funeral, is immediately transported to the hospital.

The rest of the production is made up of a series of snapshots of the real agony of the protagonist, who goes through the successive states of the Buddhist bardo – from life, through dream-like ravings, moments of tranquillity, the painful process of dying and, finally, to a state of readiness to be reborn. Don Giovanni will be guided on this journey by the Commendatore – in the dual form of the spirit of the murdered man (the actor Norbert Stöß) and one of his past or future incarnations (the singer Tijl Faveyts, made to look like a Buddhist emperor, as if taken straight from Robert Wilson’s theatrical visions). He will be accompanied by Leporello, who soon turns out to be himself, or, more precisely, the doubting aspect of his dissociated self (which Serebrennikov, somewhat in the style of early Castorf, emphasises by means of two neon props with the words “SI” and “NO”); the pregnant nurse Zerlina and her wimpish partner Masetto, a work colleague (the only reasonably real characters from Don Giovanni’s ravings); and phantoms of the past – the demonic Donna Anna, torn between her hatred of the assassin and her own father, the helpless Don Ottavio, the genuinely heartbroken Don Elviro, and his mute friend Donna Barbara (the actress Varvara Shmykova), who at some point will also become the object of the Great Rake’s designs. Everything culminates in perhaps the most spectacular “hellscension” scene I have ever seen in the theatre – in a convention reminiscent of both the great ball at Satan’s from Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (with Don Giovanni having a bit of Woland or Wotan in him) and naive plebeian theatre created by the simplest of means.

And then silence will fall for a while, followed, instead of the final sextet, by the first notes of the Requiem. An aging Don Giovanni, portrayed by the phenomenal dancer Fernando Suels Mendoza, will embark on the final leg of the journey and reach its end – and, at the same time, a new beginning – gradually regaining his balance and climbing up a vertical wall of pinewood.

There was too much of everything. There were questionable ideas – such as adding Ilya Shagalov’s projections that contributed little to the plot, or interrupting the musical narrative with excerpts from the Book of the Dead recited by Stöß. There were superfluous, though irresistibly funny, elements, including those in the feast scene, when Donna Anna, Don Elviro and Don Ottavio sneaked into the palace in ceremonial Masonic attire. There were moments that dragged on and too many symbols in the fragments of the Requiem crowning the whole. There were gestures that were too journalistic – when a banner appeared on stage stating that the aria “Il mio tesoro” would not be performed due to the cuts in Berlin’s culture budget. In fact, it was not performed because the creative team opted for the so-called Viennese version of the opera – with all the consequences of that decision, including the inclusion of Leporello and Zerlina’s duet “Per queste tue manine” in Act II.

Tommaso Barea (Leporello) and Bruno de Sá (Don Elviro). Photo: Frol Podlesnyi

It certainly was not a Don Giovanni for beginners, but neither were we dealing with a fashionable but inept Regietheater, in which the production team members treat music only as an excuse to pursue their own vision, detached from the work. Musically, it was a performance of surprisingly high quality – also taking into account the difficult acoustics of the Schiller Theater, where the Komische Oper company has moved while its home is being renovated. James Gaffigan conducted the whole in tempi that were very brisk, but corresponded to the concept formulated by Serebrennikov, a director with great sensitivity to the nuances of the score, which he demonstrated in, for example, the perfectly acted out recitatives. The most publicised soloist of the evening, Bruno de Sá, handled the part entrusted to him stylistically and technically better than many women singing Donna Elvira today: only at times did his beautiful soprano fail to sufficiently cut through the sound of the orchestra. I have more reservations about Adela Zaharia (Donna Anna), who has a powerful soprano with a decidedly dramatic tone, but one that is too wide for the part and too often overwhelming the singer’s stage partners. Penny Sofroniadou, who sang Zerlina, was much better when it came to controlling the surprisingly large volume of her voice. Among the male cast I was a little disappointed with Tijl Faveyts, whose bass was not expressive enough for the role of the Commendatore. Philipp Meierhöfer, on the other hand, was very convincing, also in terms of acting, in the role of Masetto. Augustín Gómez, who has a fairly small, but agile and handsome tenor, presented a rather stereotypical figure of a weak and passive Don Ottavio – I continue to dream of a staging in which the director would put enough emphasis on the second of the essential aspects of Mozart’s masterpiece: faithfulness against all odds. In the solo parts of the Requiem the voices of Sofroniadou, Gómez and Faveyts were joined by the alto of Virginie Verrez, thick but with a bit too much vibrato.

Perhaps the greatest asset of the production was the superbly matched duo of Don Giovanni and Leporello – Hubert Zapiór and Tommaso Barea, respectively, singers bursting with youthful energy, bravely tackling their excessive, at times acrobatic acting tasks. Most importantly, singers with a similar type of voice, a very masculine, deep and yet colourful baritone, in Zapiór’s case lightened up by a distinctive “grain”. Mozart and Da Ponte would have been over the moon: if the whole thing had been for real, only this minor detail would have made it possible to distinguish the master from the servant in the general confusion of the identity-swapping episode.

This was the closure of the Berlin Da Ponte Trilogy, which, in fact, is not a trilogy. At the Komische Oper it was brought together not only by the librettist and the director’s controversial, fiercely debated vision, but also by the vocal talent – backed by excellent acting skills – of Hubert Zapiór, the performer of the main roles in all three productions. He is a young and very promising artist. If we want to enjoy his performances in Poland, it is time to look around for a musical stage director, a suitable theatre and a conductor sensitive to singing.

Translated by: Anna Kijak