Każdy może mieć dobrą śmierć

Niektórzy mówią, że Kiriłł Sieriebrennikow jest Meyerholdem na miarę naszych czasów. Z pewnością jest najbardziej rozpoznawalnym dysydentem wśród rosyjskich artystów: po tym, jak spędził prawie dwa lata w areszcie domowym za rzekomą defraudację środków publicznych, po iście kafkowskim procesie, zakończonym wyrokiem grzywny, karą trzyletniego więzienia w zawieszeniu oraz zakazem opuszczania kraju, wreszcie po tym, jak w konsekwencji stracił stanowisko dyrektora artystycznego Centrum Gogola, z którego w niespełna dekadę uczynił jeden z najprężniejszych ośrodków niezależnej sztuki teatralnej na świecie.

Sieriebriennikow wyjechał do Berlina w marcu 2022 roku, w następstwie decyzji o uchyleniu wyroku, wydanej miesiąc po inwazji Rosji na Ukrainę. Wszczętą przez jego kraj wojnę potępił otwarcie już w maju, przy okazji premiery filmu Żona Czajkowskiego na festiwalu w Cannes. W Rosji część jego spektakli od razu spadła z afisza, z innych wymazano jego nazwisko. I tak miał więcej szczęścia niż Meyerhold, oskarżony o współpracę z wywiadem japońskim i brytyjskim, poddany wielomiesięcznym torturom i rozstrzelany w 1940 roku. Obaj, zarówno Meyerhold, jak i Sieriebriennikow, wikłali się w skomplikowane układy z władzą. Trudno któregokolwiek nazwać koniunkturalistą, przynajmniej w dzisiejszym tego słowa znaczeniu. A jednak próbują, także w Polsce, gdzie proces wymazywania kultury rosyjskiej zaszedł najdalej spośród wszystkich krajów Europy (z poniekąd zrozumiałych względów). Próba tłumaczenia dramatycznych wyborów i zawiłości kariery Sieriebriennikowa – nieukrywającego swej orientacji geja, syna rosyjskiego Żyda i mołdawskiej Ukrainki, urodzonego w Rostowie nad Donem, gdzie w 1942 roku, w Wężowym Parowie nieopodal miasta, dokonano największego mordu na ludności żydowskiej w wojennej historii ZSRR – uchodzi w niektórych kręgach za podobny nietakt, jak usprawiedliwianie księżniczki z Wyznań Rousseau za jej lekceważący stosunek do ciepiących głód chłopów.

Porównanie Sieriebriennikowa z Meyerholdem jest wszakże pod wieloma względami zasadne. Legendarny reformator teatru radzieckiego też był ekstrawaganckim buntownikiem, również szokował publiczność, burzył konwencje, czerpał z najrozmaitszych stylów inscenizacji. Od swoich aktorów wymagał absolutnego zaangażowania i niewiarygodnej sprawności fizycznej. Przedstawienia Meyerholda wzbudzały zachwyt albo gwałtowny sprzeciw: nikogo nie pozostawiały obojętnym. Podobnie jest z dorobkiem Sieriebriennikowa, zdaniem jednych genialnego wizjonera, w opinii drugich reżysera skandalicznie przereklamowanego, który odcina kupony od stosunkowo niedawnych prześladowań ze strony putinowskiego reżimu.

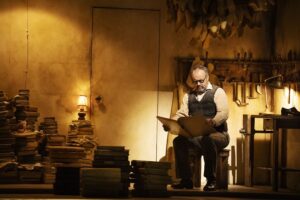

Hubert Zapiór (Don Giovanni). Fot. Frol Podlesnyi

Mnie w jego teatrze uwodzi czysty żywioł aktorski oraz dawno w Polsce zapomniana, a może nigdy nie ceniona zbyt wysoko umiejętność przełamywania patosu groteską, rozładowywania napięcia ironią i czarnym humorem. Owszem, spektakle Sieriebriennikowa są z reguły przeładowane pomysłami, czasem niezbyt spójne, pełne nieczytelnych aluzji i tropów prowadzących donikąd. Ale jeśli nawet irytują, nie sposób od nich oczu oderwać, potem zaś wyrzucić z głowy kłębiących się w niej refleksji.

Dlatego pojechałam do Berlina na premierę ostatniego członu tak zwanej Trylogii Da Ponte, od dwóch lat z okładem realizowanej przez Sieriebriennikowa z zespołem Komische Oper. Poprzednie dwie części odpuściłam sobie ze względu na chwilowy przesyt zarówno Così fan tutte, jak i Weselem Figara. Historia ukaranego rozpustnika zapowiadała się jednak prowokacyjnie nawet na tle uprzednich dokonań reżysera. Po pierwsze, Rosjanin obwieścił całość pod tytułem Don Giovanni / Requiem, co zapachniało wcześniejszymi mozartowskimi eksperymentami Teodora Currentzisa. Po drugie, postanowił przepuścić narrację opery przez pryzmat odniesień do Tybetańskiej Księgi Umarłych. Po trzecie – zastąpić postać Donny Elwiry męską ofiarą podbojów Don Giovanniego, czyli Donem Elviro w osobie brazylijskiego sopranisty Brunona de Sá.

Zapowiadała się więc co najmniej piękna katastrofa, tymczasem wyszedł z tego spektakl porywający tempem, kipiący na przemian grozą i dowcipem, na premierze co rusz przerywany oklaskami i wybuchami śmiechu na widowni. Owszem, to znów przedstawienie nadmiarowe, czerpiące pełnymi garściami zarówno z wcześniejszych produkcji Sieriebriennikowa (między innymi, co nie dziwi, z Małych tragedii Puszkina, wystawionych w Centrum Gogola, kiedy reżyser przebywał już w areszcie domowym), jak i ze „wszystkich środków wykorzystanych w innych sztukach”, jak u Meyerholda. I znów jest to spektakl, który pozostawia więcej pytań niż odpowiedzi, być może nieznanych także twórcy inscenizacji. Są w nim najbardziej rozpoznawalne elementy teatru Rosjanina – od snów i majaków, przez nieoczywiste czasem zwielokrotnienie postaci, na porwanej narracji skończywszy.

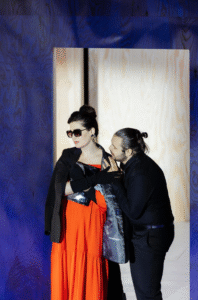

Adela Zaharia (Donna Anna) i Augustín Gómez (Don Ottavio). Fot. Frol Podlesnyi

A jednak się to ogląda – pewnie dlatego, że Sieriebriennikow, mimo pozornego wywrócenia wszystkiego na nice, wciąż uwypukla najistotniejszy aspekt historii tytułowego bohatera. To nie jest opowieść o rozwiązłości ani obsesji, to opowieść o mechanizmach władzy oraz jej związkach z seksem. Homoerotyczny podtekst wprowadzenia postaci Dona Elviro schodzi zatem na dalszy plan: wiek, płeć i orientacja „ofiar” nie mają dla Don Giovanniego żadnego znaczenia, podobnie jak nie miały w przypadku Casanovy, największego kochanka wszech czasów. Ten spektakl władzy Sieriebriennikow uzupełnia jednak zaskakującą konkluzją: że zstąpienie do piekieł przedśmiertnej agonii może dać szansę nawet łotrowi i wpłynąć na dalszy los świata. Stąd odwołanie do Tybetańskiej Księgi Umarłych i Jungowskich archetypów. Stąd pomysł, żeby objaśnić wszystko od końca i rozpocząć akcję już na dźwiękach uwertury, brawurową sceną rzekomego wskrzeszenia Don Giovanniego na jego własnym pogrzebie.

A scena to arcyrosyjska, rozegrana na kilku planach, w dekoracjach prostszych niż u Meyerholda, których podstawą są doskonale organizujące przestrzeń pudła z surowego drewna sosnowego (ustawiane w najrozmaitszych konfiguracjach, zostaną z nami do końca spektaklu). Grupka groteskowych żałobników żegna protagonistę niczym radzieckiego dygnitarza. Żeby ucałować zmarłego, trzeba nachylić się wpół przez krawędź otwartej trumny, czasem wspiąć się do niej po schodkach, po czym odegrać przed resztą zgromadzenia stosowny spektakl rozpaczy. Tymczasem w sąsiednim pudle ubrani na czarno ochroniarze (znakomita choreografia i ruch sceniczny Evgeny’a Kulagina) desperacko zmagają się z trupem Komandora, próbując zapakować go w czarny worek na zwłoki. Pośrodku tego pandemonium Don Giovanni zaczyna zdradzać oznaki życia i ku wyraźnej frustracji pogrążonych w fałszywej żałobie uczestników pogrzebu zostaje natychmiast przetransportowany do szpitala.

Dalszy ciąg przedstawienia jest szeregiem luźnych migawek z prawdziwej agonii bohatera, który przechodzi przez kolejne stany buddyjskiego bardo – od życia, przez senne majaki, chwile wyciszenia, bolesny proces umierania aż po stan gotowości do ponownych narodzin. Przewodnikiem po tej podróży będzie mu Komandor – w dwojakiej postaci ducha zamordowanego (aktor Norbert Stöß) oraz któregoś z jego poprzednich lub przyszłych wcieleń (śpiewak Tijl Faveyts, ucharakteryzowany na buddyjskiego cesarza, jakby żywcem wziętego z teatralnych wizji Roberta Wilsona). Towarzyszyć Don Giovanniemu będą Leporello, który wkrótce okaże się nim samym, a ściślej wątpiącym aspektem jego oddzielonej jaźni (co Sieriebriennikow, trochę w stylu wczesnego Castorfa, podkreśli użyciem dwóch neonowych rekwizytów z napisami „SI” i „NO”); ciężarna pielęgniarka Zerlina i jej ciapowaty partner Masetto, kolega z pracy (jedyne w miarę realne postacie z rojeń Don Giovanniego); oraz zjawy przeszłości – demoniczna Donna Anna, rozdarta między nienawiścią do zabójcy i własnego ojca, bezradny Don Ottavio, autentycznie złamany rozpaczą Don Elviro oraz jego niema przyjaciółka Donna Barbara (aktorka Varvara Shmykova), która w pewnym momencie też stanie się przedmiotem zakusów Wielkiego Rozpustnika. Wszystko skulminuje się w bodaj najbardziej spektakularnej scenie „wpiekłowstąpienia”, jaką widziałam w teatrze – w konwencji przywodzącej na myśl zarówno wielki bal u szatana z Mistrza i Małgorzaty Bułhakowa (z Don Giovannim upozowanym już wcześniej ni to na Wolanda, ni to na Wotana), jak i naiwny, realizowany najprostszymi środkami teatr plebejski.

A potem na chwilę zapadnie cisza i zamiast finałowego sekstetu zabrzmią pierwsze dźwięki Requiem. W ostatni etap podróży wyruszy postarzały Don Giovanni w osobie fenomenalnego tancerza Fernanda Suelsa Mendozy i dotrze do jej kresu – a zarazem nowego początku – stopniowo odzyskując równowagę i pnąc się w górę po pionowej ścianie z sosnowego drewna.

Było tego wszystkiego za dużo. Były pomysły wątpliwe – choćby uzupełnienie scenografii niewiele wnoszącymi do akcji projekcjami Ilyi Shagalova albo przerywanie narracji muzycznej recytowanymi przez Stößa fragmentami Księgi Umarłych. Były elementy zbędne, choć nieodparcie zabawne, między innymi w scenie uczty, kiedy Donna Anna, Don Elviro i Don Ottavio wkradają się do pałacu w ceremonialnych strojach masońskich. Były dłużyzny i nadmiar symboli w wieńczących całość fragmentach Requiem. Były też gesty zanadto publicystyczne – kiedy na scenie pojawił się transparent z informacją, że aria „Il mio tesoro” nie zostanie wykonana z powodu cięć w budżecie kulturalnym Berlina. Tymczasem nie została wykonana dlatego, że twórcy przestawienia wybrali tak zwaną wersję wiedeńską – ze wszystkimi tej decyzji konsekwencjami, między innymi uwzględnieniem duetu Leporella i Zerliny „Per queste tue manine” w II akcie.

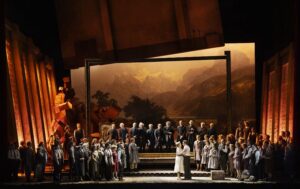

Scena z Requiem. Na pierwszym planie Fernando Suels Mendoza. Fot. Frol Podlesnyi

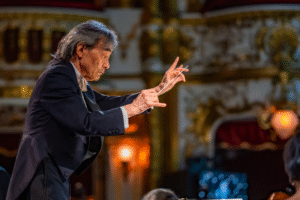

Nie był to z całą pewnością Don Giovanni dla początkujących, ale nie mieliśmy też do czynienia z tyleż modnym, ile nieudolnym teatrem reżyserskim, w którym inscenizatorzy traktują muzykę wyłącznie jako pretekst do zrealizowania własnej, oderwanej od dzieła wizji. Muzycznie zaś było to przedstawienie na zaskakująco wysokim poziomie – zważywszy także na trudną akustykę Schiller Theater, dokąd zespół Komische Oper przeniósł się na czas remontu macierzystej siedziby. James Gaffigan prowadził całość w tempach bardzo wyśrubowanych, korespondujących jednak z koncepcją Sieriebriennikowa, reżysera obdarzonego dużą wrażliwością na niuanse partytury, czego dowiódł między innymi w doskonale poprowadzonych aktorsko recytatywach. Najszumniej zapowiadany solista wieczoru, czyli Bruno de Sá, pod względem stylistycznym i technicznym poradził sobie z powierzoną mu partią lepiej niż niejedna współczesna wykonawczyni roli Donny Elwiry: tylko chwilami jego przepiękny sopran niedostatecznie przebijał się ponad dźwięk orkiestry. Więcej zastrzeżeń mam do Adeli Zaharii (Donna Anna), dysponującej potężnym sopranem o zdecydowanie dramatycznym zabarwieniu, za szerokim do tej partii i zbyt często przytłaczającym scenicznych partnerów. Nad zaskakująco rozległym wolumenem swego głosu znacznie lepiej panowała Penny Sofroniadou, wcielająca się w postać Zerliny. W męskiej obsadzie trochę rozczarował mnie Tijl Faveyts, śpiewający basem nie dość wyrazistym do partii Komandora. Bardzo przekonująco, także pod względem aktorskim, wypadł za to Philipp Meierhöfer w roli Masetta. Dysponujący niedużym, ale giętkim i urodziwym tenorem Augustín Gómez zbudował dość stereotypową postać słabego i biernego Don Ottavia – wciąż marzy mi się inscenizacja, której twórca położyłby dostateczny nacisk na drugi z istotnych aspektów Mozartowskiego arcydzieła: wierność na przekór wszelkim zrządzeniom losu. W partiach solowych Requiem do wymienionych już głosów Sofroniadou, Gómeza i Faveytsa dołączył gęsty, choć odrobinę zanadto rozwibrowany alt Virginie Verrez.

Bodaj największym atutem spektaklu okazał się znakomicie dobrany duet Don Giovanniego i Leporella – odpowiednio Huberta Zapióra i Tommasa Barei, śpiewaków tryskających młodzieńczą energią, dzielnie stawiających czoło wygórowanym, czasem wymagającym wręcz akrobatycznych umiejętności zadaniom aktorskim. Co jednak najważniejsze, śpiewaków obdarzonych podobnym typem głosu, bardzo męskim, głębokim, a zarazem kolorowym barytonem, w przypadku Zapióra dodatkowo rozświetlonym charakterystycznym „groszkiem”. Mozart i Da Ponte byliby w siódmym niebie: gdyby rzecz działa się naprawdę, tylko ten drobny szczegół pozwoliłby odróżnić pana od sługi w ogólnym zamieszaniu epizodu z zamianą tożsamości.

I tak oto domknęła się berlińska Trylogia Da Ponte, która w istocie trylogią nie jest. W Komische Oper połączyły ją w całość nie tylko osoba librecisty oraz kontrowersyjna, wzbudzająca żarliwe dyskusje wizja reżyserska, lecz także poparty świetnym warsztatem aktorskim talent wokalny Huberta Zapióra, wykonawcy głównych partii we wszystkich trzech produkcjach. To młody i bardzo obiecujący artysta. Jeśli chcemy się nim nacieszyć w Polsce, pora już teraz rozejrzeć się za muzykalnym reżyserem, odpowiednią sceną i wrażliwym na śpiew dyrygentem.