Fine Trills Make Fine Birds

When Gottfried Keller lost his father and found himself alone in this world with his mother and younger sister, he was only five years old. Rudolf – a turner, self-taught builder and head of the Keller family – died of tuberculosis shortly after turning thirty, having previously buried four of his six children with wife Elisabeth. In many respects he was an extraordinary man: as a teenage journeyman he travelled across Europe, returning to Zurich not only as a comprehensively educated craftsman, but also a mature, freedom-loving citizen. Before he departed this world, he had given his wife detailed instructions on how to instil his ideals into his only surviving son. The widowed Elisabeth was barely able to make ends meet, but she did do all he could not to disappoint her husband’s ambitions. Little Gottfried was brought up in a household free from any prejudice and carefully watched the reality around him. After the failure of the November Uprising Polish émigrés seeking refuge under Mrs Keller’s hospitable roof became a permanent part of this reality. What the future writer and poet gained from those days were not just beautiful memories of friendship – memories he referred to in his autobiographical novel Green Henry, but also a lasting interest in the cause of political refugees and their fight for their lost statehood.

More waves of émigrés from Poland came to Switzerland after the Spring of the Peoples and the failed January Uprising. In 1863 Gottfried Keller – at that time already the secretary of the Canton of Zurich – founded, together with Count Władysław Plater, the Central Committee for Aiding Poles. First, they financed the purchase of weapons for the insurgents and after the fall of the independence uprising they organised all kinds of support for nearly two thousand emigrants. Although there were some impostors among true heroes, nothing would shake Keller’s sympathy for the newcomers from a distant country in the east of Europe. Even if he did admonish them, he did so delicately and with compassion – like in the short story, written more or less at that time but published only in 1874, Kleider machen Leute (which can be freely translated as “clothes do make the man”). Its protagonist is a young tailor, Wenzel Strapinski, who has just lost his job and has set off “on an unpleasant November day” to seek luck elsewhere. He had to content himself with just a few snowflakes for his breakfast and had only a thimble in his pocket – but he looked beautiful in his handmade Sunday best, a velvet-lined cape and fur hat. Perhaps this is why the coachman from a coach he passed on the way offered him a lift to a nearby town, introduced him to everyone as a Polish count and then disappeared before the young man had time to protest. Confused, Wenzel assumes the role of an aristocrat – first unwittingly, then deliberately, when he wins the affection of the daughter of the city council chairman. Although he will be exposed by a jealous rival, all will end well: his beloved will declare that she does not have to be a countess, that it will be enough for her to become the wife of a true master tailor.

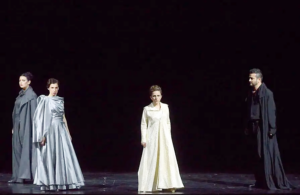

Photo: Serghei Gherciu

Keller’s short story enjoyed great popularity in the German-speaking world at the time, also in Austria-Hungary, where many imperial subjects built their status with methods similar to Wenzel’s. The subjects included Zemlinsky’s father – a Viennese-born son of an Austrian Catholic mother and a father from Žilina, Hungary – who added the noble preposition “von” to his surname and before marrying Klara Semo, daughter of a Bosnian Muslim woman and a Sephardic Jew from Sarajevo, converted to Judaism. Thus little Alexander was born as a fully-fledged member of the Viennese Jewish community, but he left it as early as in 1899 following the Dreyfus affair and the growing wave of anti-Semitism. He began composing the comic opera Kleider machen Leute in 1907, after the earlier successes of Sarema and Es war einmal, and the failed premiere of Der Traumgörge, which was planned at Vienna’s Staatsoper under Mahler’s baton, but which did not take place after Mahler resigned as the company’s music director shortly before the first performance. The libretto to Kleider machen Leute – as in the case of the unlucky Traumgörge – was written by Leo Feld, who significantly condensed the narrative and made it somewhat lighter than in Keller’s original. The premiere of the first, three-act version took place in 1910 at Vienna’s Volksoper. The critics cool reception prompted Zemlinsky to introduce major changes into the libretto and the score. After a few failed attempts to have the revised two-act version of the opera staged, Kleider machen Leute was revived in 1922 at the Neues Deutsches Theater, the current home of the State Opera in Prague.

The work, rediscovered only in the 1980s, arrived in the Prague theatre in February 2023, as part of the huge four-season Czech-German project “Musica non grata”, the main aim of which is to bring back from obscurity the oeuvres of artists active in inter-war Czechoslovakia who were eliminated from musical life after the Nazis came to power: eliminated because of their origin, religion and political views, as well as their gender and sexual orientation. Launched in 2020 under the aegis of Prague’s National Theatre and financially supported by the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany, the project can already be regarded as one of the most successful initiatives of this kind in Europe – geared towards introducing forgotten works into the cultural bloodstream permanently, rather than towards a one-off, superficial effect that caters to a less sophisticated audience.

Photo: Serghei Gherciu

Hence the idea to stage Kleider machen Leute with mainly local musicians, led by two artists whose collaboration had previously been appreciated, when Janáček’s Katia Kabanova was staged at Komische Oper Berlin: the Dutch director Jetske Mijnssen and the Lithuanian conductor Giedrė Šlekytė. Mijnssen represents a theatre-making style typical of her country, pared-down in terms of the means of expression, drawing at times on Willy Decker’s austere minimalism. In her interpretation the action of Zemlinsky’s opera takes place primarily on the proscenium, within a space delimited by Herbert Murauer’s symmetrical, tripartite sets (ingeniously lit by Bernd Purkrabek), the main element of which is a semicircular wall placed on the revolving stage. The sets are complemented by simple pieces of furniture, sometimes serving as far from obvious props (an example is Wenzel’s journey in a coach made up of several chairs, showing the protagonist in a different grotesque position with each turn of the revolving stage). The director balanced out the sparseness of the sets with an exaggerated, almost expressionistic theatrical gesture – generally to good effect, although Zemlinsky’s dancing score could have done with more choreographic work (Dustin Klein, who was responsible for the stage movement, opted instead for pantomime, spectacular in, for example, the slow-motion scene featuring the pursuit of the exposed fake count). However, the most important error in the staging lay in the insufficient highlighting of Wenzel’s innate elegance. With the exception of his fur hat, the young tailor did not stand out in any way from the crowd of characters dressed by Julia Katharina Berndt in costumes from the inter-war period – from straw pork pie hats from the wild 1920s to the jazzy zoot suits characteristic of Polish Bikini Boys from a later period.

Yet Mijnssen’s clean and precise direction went side by side with the dramaturgy of the work, although it did lead several soloists into an acoustic trap – their voices, emphasised on the proscenium, often sounded unnatural, standing out excessively from the orchestral fabric. Those who emerged unscathed from this predicament were the two lead singers – Joseph Dennis as Wenzel, an artist boasting a strong, resonant and perfectly controlled tenor, and Jana Sibera as Nettchen, a singer with a soft, beautifully saturated and very sensuous soprano (especially in the particularly well-sung aria “Lehn deine Wang’ an meine Wang’” with Heine’s text at the beginning of Act II). Fine moments also came from Ivo Hrachovec in the bass part of the Innkeeper and the baritone Markus Butter singing the role of Melchior Böhni, a rejected suitor for Nettchen’s hand. Other members of the huge cast of a dozen or so singers were less successful in battling the capricious acoustics. It is hard for me to judge to what extent this could have been prevented by Giedrė Šlekytė, who, apart from failing to control the capricious acoustics, led the State Opera ensembles very efficiently and energetically, with a perfect sense of the mosaic style of this composition, which combines late Romantic inspirations by the music of Wagner and Richard Strauss – and, by extension, also the young Schönberg – with a truly Mozartian bravura in the shaping of group scenes, and the ever-present lightness of Viennese operetta.

Photo: Serghei Gherciu

Kleider machen Leute is not a masterpiece on a par with Der Zwerg or Eine florentinische Tragödie. There is no doubt, however, that it deserves love: as does the modest and shy Wenzel Strapinski: a fake count, true, yet still endearing in his large, black velvet-lined capes, with a pale, noble countenance of a Polish émigré.

Translated by: Anna Kijak