Zamyka się piekło, otwiera się niebo

Znienawidzony w Polsce „lockdown” nigdy nam się nie kojarzył z tym, co trzeba – czyli narzędziem kompleksowej walki z pandemią, opartym na Erazmiańskiej maksymie wyższości profilaktyki nad leczeniem. Narzędziem wymagającym od władz uczciwości i konsekwencji, od ekspertów – wnikliwości i pokory w starciu z nieznanym, od społeczeństw – wrażliwości etycznej, solidarności i empatii. Uciążliwe i niezrozumiałe dla większości Polaków restrykcje okazały się z wielu powodów nieskuteczne. Zamiast dać nam nadzieję, zostawiły w przeświadczeniu, że godzą w naszą wolność, stają się elementem bezwzględnej walki politycznej – że to one, nie sama choroba, prowadzą do tysięcy ludzkich tragedii i bezprecedensowego kryzysu opieki zdrowotnej.

Przede wszystkim jednak zniszczyły w nas resztki i tak niezbyt rozwiniętego myślenia wspólnotowego – nieodzownego warunku przetrwania, dzięki któremu Wielka Brytania wychodzi właśnie z lockdownu, o jakim się w Polsce nikomu nie śniło. Wychodzi nie tylko zdrowsza i bardziej rozważna, ale też wyposażona w szereg umiejętności rozwiniętych w najuciążliwszych chwilach odosobnienia. Inicjatywy muzyczne Brytyjczyków obserwuję od początku pandemii – z narastającym podziwem. Kultura na Wyspach nie zamarła ani na chwilę: po prostu zamknęła się w domach, łącząc się ze światem za pośrednictwem nowoczesnych technologii, umożliwiających nie tylko kontakt z publicznością, ale też kontynuację wcześniejszych przedsięwzięć i snucie konstruktywnych planów na przyszłość.

Owocem takich żmudnych przygotowań jest pierwszy, wciąż jeszcze wirtualny festiwal wielkanocny Oxford Bach Soloists – zespołu założonego w 2015 roku przez Toma Hammonda-Daviesa i od początku działającego w duchu muzycznej wspólnoty, jednoczącej uznanych śpiewaków i muzyków orkiestrowych, studentów, amatorów, edukatorów oraz badaczy reprezentujących najrozmaitsze dyscypliny, od historii i teologii począwszy, skończywszy na literaturoznawstwie i naukach filologicznych. Zespół i jego szef postawili przed sobą cel dość niezwykły: przedstawienie całości spuścizny wokalnej Jana Sebastiana Bacha w porządku chronologicznym i w powiązaniu z kontekstem oraz przeznaczeniem każdego dzieła z osobna. Na realizację przeznaczyli sobie dwanaście lat – kto wie, czy pozornie stracony rok wielkiej zarazy nie wyposażył ich w tym ciekawsze narzędzia, które uda się spożytkować z sukcesem w kolejnych sezonach.

Nick Pritchard (Ewangelista)

W programie tegorocznego festiwalu znalazły się kantaty BWV 4 i BWV 31 oraz Oster-Oratorium; z rozmaitych względów skupię się jednak na Pasji Janowej, arcydziele, która od pewnego czasu szturmem wraca do łask wykonawców i słuchaczy. Hans-Georg Gadamer pisał w Aktualności piękna, że fenomen muzyki pasyjnej „sięga swym zakresem od najwyższych wymogów kultury artystycznej, muzycznej i historycznej po najprostsze potrzeby i wrażliwość serca ludzkiego”. Jest właśnie zjawiskiem wspólnotowym: tłumaczy sens i cel cierpienia, uczy współczucia, pomaga udźwignąć brzemię własnych strachów i nieszczęść. W niezwykłym przedsięwzięciu Oxford Bach Soloists udało się spełnić wszelkie warunki wyszczególnione przez Gadamera i wynieść Johannes-Passion do rangi potężnej metafory obecnego kryzysu.

Obydwie zachowane pasje Bacha pochodzą z późnego okresu jego twórczości, po objęciu posady kantora lipskiego kościoła świętego Tomasza w 1723 roku. Poprzednikiem mistrza był Johannes Kuhnau, organista i teoretyk muzyki, twórca Pasji według świętego Marka, od 1721 roku wykonywanej na przemian podczas nieszporów wielkopiątkowych u świętego Tomasza i świętego Mikołaja w Lipsku. Pisząc Pasję Janową BWV 245, Bach spodziewał się jej wykonania w macierzystej świątyni, tymczasem zgodnie z lipską praktyką premiera nowej pasji miała przypaść w kościele świętego Mikołaja. Nieporozumienie wyszło na jaw zaledwie cztery dni przed uroczystym nabożeństwem. Kantor musiał w ostatniej chwili skompletować potężny zespół wokalno-instrumentalny z muzyków obydwu świątyń: utwór przewyższał rozmiarami zarówno wcześniejsze kantaty, jak i Magnificat, pierwszą znaczącą kompozycję dla głównych kościołów Lipska. Mimo perturbacji Pasja Janowa w wersji pierwotnej zabrzmiała 7 kwietnia 1724 roku. Jako punkt wyjścia libretta posłużyła Ewangelia według świętego Jana, uzupełniona kompilacją pojedynczych wierszy, między innymi z popularnej w owym czasie Brockes Passion. Niespójność warstwy tekstowej skłoniła Bacha do szeregu późniejszych modyfikacji dzieła. Być może dlatego do Pasji Janowej przylgnęła etykieta utworu niekompletnego, przerwanego w połowie zamysłu.

Jak bardzo niezasłużona to etykieta, dowodzą coraz liczniejsze interpretacje najwybitniejszych specjalistów od wykonawstwa historycznego. Oxford Bach Soloists, wzbogaceni także o własne doświadczenia Pasji Janowej, realizowanej w ubiegłym roku w ścisłej izolacji, postanowili nadać swemu przedsięwzięciu dodatkowy wymiar. Zaprosili do współpracy Thomasa Guthriego, angielskiego reżysera, śpiewaka i aktora, od lat zafascynowanego inscenizacją dzieła muzycznego nie tylko przez dialog artystów z odbiorcą, ale wręcz w kategoriach wspólnotowości – wpisanej w narrację utworu, doświadczanej cieleśnie i zmysłowo przez samych wykonawców.

Peter Harvey (Jezus). W głębi Hugh Cutting.

Guthrie-reżyser jest jak szczere i prostoduszne dziecko: wie, że w teatrze dzieją się cuda i umie o tym przekonać swoich widzów. W 2017 roku doświadczyłam tego na własnej skórze, na przedstawieniu Czarodziejskiego fletu w Longborough, kiedy do tego stopnia wszedł w rolę twórcy spektaklu, że wyreżyserował nawet niespodziewaną przerwę techniczną w pierwszym akcie, zwracając się do publiczności jak do gromady przerośniętych przedszkolaków: ku wielkiej owych przedszkolaków uciesze. Guthrie porównał kiedyś ekspresję śpiewaków do płaczu niemowlęcia, które nie spocznie, aż przekaże otoczeniu swój ważki komunikat. Nie spodziewałam się jednak, że w Pasji Janowej we wnętrzu oksfordzkiego Christ Church spojrzy na dramat Jezusa, jego sędziów, uczniów i oprawców, oczami dziecka przedwcześnie dojrzałego i rozumiejącego z tej tragedii więcej niż niejeden dorosły.

Dało się to odczuć już w początkowym, opartym na muzycznych i retorycznych antytezach chórze „Herr, unser Herrscher”, uzmysławiającym paradoks chwały i upodlenia Jezusa. Guthrie gra w swojej inscenizacji dosłownie każdym gestem, kolorem i rekwizytem. Tam, gdzie w muzyce jest ziemia i świat doczesny, obraz skrzy się jaskrawymi barwami. Kiedy Bach przenosi nas w sferę Niebios, Guthrie maluje ją w pastelowych, wręcz nierealnych odcieniach. Męka Chrystusa jest czarno-biała, spowita szarą mgłą bólu. Mistrzowska robota operatorska przywodzi na myśl skojarzenia z dawnym malarstwem, w którym artyści przemycali w pejzaż biblijny elementy własnego świata. W inscenizacji Guthriego pełnoprawnymi towarzyszami drogi krzyżowej są umieszczone na przesuwnych statywach mikrofony, migające diodami kamery, porzucone w bocznej nawie ubrania i futerały na instrumenty.

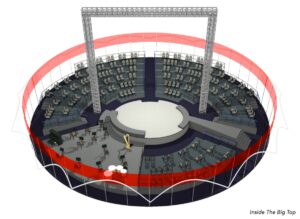

Scena zbiorowa

Z równą pieczołowitością reżyser zadbał o wewnętrzne napięcie między wszystkimi uczestnikami akcji dramatycznej, począwszy od głównych postaci, skończywszy na pojedynczych muzykach orkiestrowych (nie muszę dodawać, że spektakl zrealizowano z pełnym poszanowaniem obowiązujących reguł dystansu fizycznego). Oksfordzka Pasja jest w równej mierze otwartą alegorią, jak i głęboko przeżytym doświadczeniem wspólnoty – z opowiadaną historią, z innymi wykonawcami, z samym sobą. Ogromna w tym zasługa Nicka Pritcharda w partii Ewangelisty – realizowanej leciutkim, pięknie otwartym w górnym rejestrze i znakomitym artykulacyjnie tenorem – który podparł swój kunszt wokalny wybornym aktorstwem, tworząc niezapomnianą postać kruchego, często bezradnego, przejętego rozpaczą świadka tragedii. Równie głęboko w pamięć zapadł mi Chrystus w ujęciu Petera Harveya: przygaszony, rozgoryczony, pełen lęku w obliczu nadciągającej śmierci. Myślę, że pewne niedostatki wolumenu w jego pięknym i świetnie prowadzonym głosie wyszły akurat na korzyść takiej koncepcji roli. Wstrząsająco ludzkim, przejętym rozterką Piłatem okazał się Alex Ashworth, dysponujący barytonem jędrnym, ruchliwym i bardzo pewnym intonacyjnie. Z pozostałych solistów warto wspomnieć o obdarzonej świetlistym, prawdziwie radosnym sopranem Lucy Cox (porywające „Ich folge dir gleichfalls mit freudigen Schritten”), kontratenorze Hugh Cuttingu, który tak śpiewa arię „Von den Stricken meiner Sünden”, że ciarki chodzą po plecach, zwłaszcza zaś o aksamitnogłosym, imponującym kulturą śpiewu i niepospolitą wrażliwością Benie Daviesie w basowym arioso „Betrachte, meine Seel, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen” ze sceny biczowania.

W śpiewie chóru ujęło mnie przede wszystkim zrozumienie tekstu, podawanego z żarliwością, bólem i współczuciem, a przy tym wzorową emisją i z zachowaniem pewnego rysu indywidualności, co akurat w wykonawstwie muzyki barokowej cenię nadzwyczaj wysoko. W zespole instrumentalnym właściwie każdy muzyk reprezentował klasę samą dla siebie. Jestem też pełna podziwu dla elegancji i skuteczności rzemiosła dyrygenckiego Toma Hammonda-Daviesa, który prowadził całość w dość trudnych warunkach akustycznych Christ Church, z muzykami rozmieszczonymi nietypowo i w dużych nieraz odstępach.

Wciąż wspominam tę Pasję i nieustannie mam nadzieję usłyszeć ją kiedyś w tym wykonaniu i zobaczyć w inscenizacji Guthriego: prostej, oszczędnej, boleśnie dającej do myślenia. Czy naprawdę trzeba tyle razy umrzeć, żeby wreszcie zmartwychwstać? Czy nie wystarczy już tego cierpienia?