W stronę czwartego wymiaru

Już niedługo dwie relacje z Niemiec: o prapremierze opery Chai Czernowin Heart Chamber w Deutsche Oper Berlin oraz nowej inscenizacji Lady Makbet mceńskiego powiatu w Oper Frankfurt. Tymczasem wróćmy jeszcze na chwilę do Bayreuth – w szkicu o tym, jakiego teatru chciał Wagner, jakiego Cosima, jej syn i wnuki, a co dzieje się teraz na Zielonym Wzgórzu. Tekst ukazał się w listopadowym numerze „Teatru” i trafi do sieci co najmniej za miesiąc, więc udostępniam go wcześniej na mojej stronie. Teatromanom polecam całą „jedenastkę”, w której między innymi refleksje Kaliny Zalewskiej po premierach nowych dramatów Marka Modzelewskiego, esej Tamása Jászaya o teatrze Kornéla Mundruczó, rozmowa Jacka Cieślaka z Jerzym Stuhrem i Jacka Kopcińskiego z Piotrem Adamczykiem oraz relacja z przedstawienia Upiorów Ibsena 23 maja 1918 roku w Petersburgu – podpisana przez niejakiego Genezypa Kapena, który kilkanaście lat później pojawi się na stronach powieści prawdziwego autora recenzji. Będzie co czytać w długie jesienne wieczory.

***

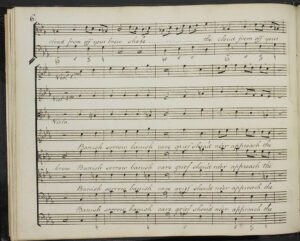

„Zielonkawy półmrok, im wyżej, tym jaśniejszy, na dole ciemniejszy. W górze rozkołysane fale, przesuwające się nieustannie z prawa na lewo. Poniżej nurt rozprasza się stopniowo w wilgotną mgłę – aż do momentu, w którym nad podłogą odsłoni się przestrzeń wysokości człowieka, pozornie wolna od wody, która przepływa nad korytem rzeki jak strzępy chmur. Z głębi wznoszą się strome urwiska, okalające całą scenę. Dno rzeki pokrywa labirynt skał o postrzępionych krawędziach, sugerujący sieć przepastnych, niknących w ciemności wąwozów. Orkiestra zaczyna grać przy zasłoniętej kurtynie”.

Notatki reżyserskie Clausa Gutha albo Davida Aldena? Nie, autorskie didaskalia Ryszarda Wagnera do Złota Renu, które siedem lat po prapremierze w Monachium doczekało się wystawienia w Festspielhausie w Bayreuth, 13 sierpnia 1876 roku, na wieczorze inaugurującym Pierścień Nibelunga, a zarazem działalność nowego teatru. Kompozytor troszczył się o tę inscenizację na wszystkich etapach jej powstawania, wcielając się w role reżysera, producenta, korepetytora muzyków, dyrygenta, śpiewaka, aktora, inspicjenta i suflera. Na widowni zasiedli między innymi cesarz niemiecki Wilhelm, cesarz Brazylii Piotr II, Friedrich Nietzsche, Anton Bruckner, Piotr Czajkowski i Ferenc Liszt.

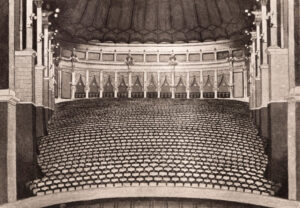

Festspielhaus w 1895 roku. Ze zbiorów Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Otwarcie Festspielhausu miało nastąpić trzy lata wcześniej. Kamień węgielny pod budowę gmachu położono już w maju 1872 roku, ale z braku pieniędzy prace wkrótce przerwano. Wagner gorączkowo pozyskiwał fundusze i oszczędzał, na czym się dało. Głównym, o ile nie jedynym priorytetem było dlań nowatorskie, pieczołowicie zaprojektowane wnętrze, spełniające wszelkie wymogi jego wizji teatru muzycznego. Walory architektoniczne budynku zeszły na dalszy plan. Kompozytor wykorzystał, a właściwie ukradł niezrealizowany projekt Opery Monachijskiej autorstwa Gottfrieda Sempera i urzeczywistnił go po swojemu – rezygnując z ozdóbek, dywanów, kosztownych obić i paradnych schodów. Fotele zastąpił składanymi krzesłami, do budowy gmachu użył najtańszego drewna, całość pokrył napinanym sufitem z płótna. Prawdę powiedziawszy, traktował Festspielhaus jako konstrukcję tymczasową i po pierwszym wystawieniu Pierścienia miał zamiar wznieść w jego miejsce coś solidniejszego.

Jak wiadomo, nie ma nic trwalszego niż prowizorka. Miłośnicy Wagnera z biegiem lat oswoili się z wyglądem teatru – obdarzeni lepszym gustem i wyczuciem proporcji bywalcy pierwszych festiwali natrząsali się z niego bezlitośnie. Mieszkańcy Bayreuth porównywali go z fabryką, młody Strawiński wyznał, że budowla kojarzy mu się z monstrualnym krematorium. Dla Wagnera liczyła się tylko koncepcja sceny, kanału orkiestrowego i widowni: jak wyszło na jaw z czasem, wykorzystanie tandetnych materiałów budowlanych paradoksalnie przyczyniło się do wyjątkowej akustyki wnętrza, która dodatkowo wzmocniła atuty przedsięwzięcia. Niemal całkowicie zakryty orkiestron, podwójne proscenium pogłębiające iluzję oddalenia publiczności od sceny, niecodzienny wówczas nakaz dawania przedstawień przy wygaszonych światłach – wszystko to pozwoliło uzyskać słynną „mistyczną przepaść”, wprowadzającą odbiorcę w teatralny sen na jawie, niezakłócony żadnym bodźcem z zewnątrz, żadną architektoniczną przeszkodą, która mogłaby rozproszyć uwagę widowni. W Wagnerowskiej świątyni Gesamtkunstwerk narodziła się współczesna reżyseria, nie tylko operowa.

W początkach istnienia festiwal przynosił potężne straty finansowe. Przetrwał w dużej mierze dzięki wsparciu ze strony państwa i wielbicieli twórczości Wagnera. Po jego śmierci dostał się pod żelazne rządy owdowiałej Cosimy, która mniej lub bardziej świadomie przyczyniła się do wypaczenia założycielskiej idei. Odżywał wielokrotnie: w 1906 przejął go syn kompozytora Siegfried, uchylając podwoje nowocześniejszej wizji teatru. Po II wojnie światowej stał się przybytkiem teatralnego minimalizmu – Wieland Wagner odrzucił narosłe z biegiem lat parafernalia „świętej tradycji niemieckiej”, żeby zdjąć z twórczości dziadka odium narzucone jej przez III Rzeszę. Przez Bayreuth przetaczały się kolejne burze: krótkotrwały nawrót konserwatyzmu wraz z końcem epoki Wielanda, zmarłego przedwcześnie na raka płuc, szturm niemieckiego teatru politycznego, skontrowany później przez zalew widowiskowych produkcji z wykorzystaniem pirotechniki i laserowych świateł.

Widownia teatru w 1904 roku. Ze zbiorów Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Samozwańczy strażnicy tradycji każdą rewolucję na Zielonym Wzgórzu witali gromkim rykiem oburzenia. Bayreuth zaczęło stopniowo tracić prestiż. W 1973 roku festiwal – bombardowany przez krytyków i wstrząsany rodzinnymi waśniami krewnych kompozytora – przeszedł pod zarząd Richard-Wagner-Stiftung. W roku 2008, po ostatecznej rezygnacji autokraty Wolfganga, młodszego i dużo mniej zdolnego brata Wielanda, bawarski minister kultury powierzył stery dwóm jego córkom: Katharinie Wagner i Evie Wagner-Pasquier. Od tamtej pory, a zwłaszcza od roku 2015, kiedy Katharinie udało się skutecznie pozbyć przyrodniej siostry, losy festiwalu w Bayreuth przypominają kiepską operę mydlaną. Rok w rok nie obywa się bez plotek, zrywania kontraktów, nagłych zmian obsadowych i oględnie mówiąc wątpliwych decyzji artystycznych. Po raz pierwszy od dekad nie ma większego kłopotu z zakupem biletów na pojedyncze spektakle, choć administratorzy gorliwie podtrzymują mit niedostępności festiwalu.

Samodzielne rządy Kathariny Wagner zaczęły się naprawdę fatalnie: od jej własnej, zaiste koszmarnej produkcji Tristana i Izoldy, która szczęśliwie zeszła z afisza po tym sezonie. Przygotowania do premiery Parsifala w 2016 roku przebiegały w atmosferze żenującego skandalu. Zarząd rozwiązał umowę z berlińskim performerem Jonathanem Meese, powołując się na względy budżetowe. Zastąpił go Uwe Eric Laufenberg i wprowadził na scenę koncepcję opracowaną pierwotnie dla Opery w Kolonii. W kuluarach szeptano, że poszło raczej o upodobanie do nazistowskiego gestu „Heil Hitler”, za którego użycie w performansie Größenwahn in der Kunstwelt Meese został postawiony przed sądem. Wagner poszła po rozum do głowy i radykalnie zmieniła front. W 2017 roku nową inscenizację Śpiewaków norymberskich przygotował Barrie Kosky, pierwszy w historii Bayreuth reżyser pochodzenia żydowskiego. W następnych sezonach przyszła pora na młodych gniewnych: po kolejnej awanturze, tym razem z Alvisem Hermanisem, który wycofał się z produkcji Lohengrina, na festiwalu zadebiutował Yuval Sharon, dostosowując swą wizję do gotowych już dekoracji i kostiumów Neo Raucha i Rosy Loy. Decyzja o wyborze Sharona zapadła zapewne po głośnym Pierścieniu Nibelunga w Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe, gdzie Amerykanin wyreżyserował Walkirię; w tym roku za Tannhäusera wziął się Tobias Kratzer, beniaminek niemieckiej krytyki i realizator ostatniej części Tetralogii w Karlsruhe.

Zarzekałam się przez wiele lat, że moja noga w Bayreuth nie postanie, a wagnerowskich uniesień będę szukać w innych, lekceważonych przez snobów teatrach. Złamałam się w tym sezonie, zaintrygowana ubiegłorocznym przedstawieniem Lohengrina, z oczywistych względów pękniętym interpretacyjnie, niemniej olśniewającym poezją wizji scenicznej. Z rozpędu zaakredytowałam się także na Parsifalu Laufenberga i postanowiłam podejść do rzeczy bez żadnych uprzedzeń.

Wieland Wagner (z lewej) i Wolfgang Wagner. Ze zbiorów Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Jak się okazało, słusznie. Przekonałam się bowiem dobitnie, że materiały filmowe nie dają choćby mętnego wyobrażenia o warstwie wizualnej spektakli na Zielonym Wzgórzu. Żaden zapis wideo nie odda surrealistycznego piękna sceny z początku II aktu Lohengrina, w której nieostre kontury dekoracji wyłaniają się z mrocznych mgieł i oparów kropka w kropkę jak w Wagnerowskich didaskaliach do Złota Renu. Żadne zdjęcie nie uchwyci majestatu rewelacyjnie oświetlonej scenografii Gisberta Jäkela w finale Laufenbergowskiego Parsifala. Kiedy pojęłam, że wszędobylskie we współczesnych inscenizacjach projekcje mogą naprawdę czemuś służyć – a takie możliwości, przy inteligentnym wykorzystaniu, daje przepastna, pozornie nieskończona scena Festspielhausu – nabrałam ochoty, by zobaczyć na żywo nowego Tannhäusera, mimo że Kratzer i tym razem stworzył spektakl przeładowany mnóstwem detali i zamiast wniknąć w intencje autora, skupił się na własnej idée fixe. Przynajmniej tak wnoszę z premierowej transmisji w internecie. Być może niesłusznie, bo na tej scenie naprawdę dzieją się cuda – skoro tak potrafią mnie wciągnąć nawet wątpliwe eksperymenty sierot po teatrze postdramatycznym, trudno mi sobie wyobrazić, w jakim stanie opuszczali ten przybytek widzowie pierwszego kompletnego Pierścienia w 1876 roku.

Żal mi Wagnera, który zmarł niespełna siedem lat po urzeczywistnieniu swego marzenia. Rzekomi strażnicy tradycji wagnerowskiej niszczą ją od stu trzydziestu lat z okładem. Jedni domagają się Walkirii w hełmach ze skrzydełkami, porośniętego łuską Fafnera i Erdy wystającej ze sceny niczym słup ogrodzeniowy; drudzy z uporem maniaka doszukują się w Wagnerowskich dramatach podtekstów politycznych, wrażej ideologii bądź zwierciadła własnych frustracji i rozczarowań. A ja sobie myślę – po pierwszej wizycie w Bayreuth – że Wagner chciał stworzyć teatr, który nie zmieści się w żadnej racjonalnej wizji rzeczywistości. Teatr, który weźmie nas w ciemnościach za rękę i niepostrzeżenie wprowadzi w świat mitu, który rozproszy ten zielonkawy półmrok i odsłoni emocje ukryte pod powierzchowną warstwą znaczeń.

Nie wszystko jeszcze stracone. Wagner zostawił spadkobiercom klucz do innego wymiaru. Drzwi jeszcze nie znaleźli, ale przynajmniej nie zgubili klucza.