It is difficult to be a prophet in one’s own country. And all the more difficult for cosmopolitan types who haven’t wanted to, been allowed to or been able to put down roots anywhere. This is exactly how it was with Józef Michał Poniatowski, about whom one can read today that he was Prince de Monte Rotondo, of the noble clan of Ciołek and a close blood relative of his namesake, Józef Poniatowski, the protagonist of a quintessentially Polish version of the Napoleon myth. The truth – as always – is more complicated.

Our prince-composer was the illegitimate son of Lithuanian treasury official Stanisław, who was an extraordinarily picturesque figure, a favorite of King Stanisław August, a confidant of his lover Empress Catherine II, a member of the Targowica Confederation, which over time began to be considered a symbol of treason. After the Partitions, Stanisław Poniatowski settled first in Austria, and then in Rome, where he bought a splendid residence on the Via Flaminia. Opposite the villa lived the modest Cassandra Luci, the wife of a brutish shoemaker who abused her mercilessly. The thoughtful prince took the poor woman under his care. From this care, five illegitimate children came into the world. One of them was Józef Michał Ksawery, born in 1816. Three years later, Stanisław gathered his informal family at his newly-acquired Monte Rotondo estate in Tuscany; in 1830, he finally married the widowed Cassandra; and in 1833, he died as the last aristocrat legally authorized to bear a Polish princely title.

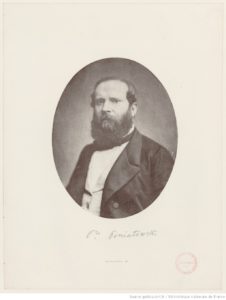

Józef Michał was acknowledged by his father already at age 6; for the legal sanction of his ancestry, however, he had to wait until 1847, when Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, intervened on his behalf – in order to name him Prince of Monte Rotondo. Poniatowski spoke no Polish at all. He was a Tuscan state envoy to Brussels, London and Paris; in 1854, he became a French citizen and received the office of senator from the hands of Napoleon III. After the emperor’s dethronement, he traveled together with him into exile to Chislehurst, in the English country of Kent. The last ruler of France died in January 1873, which hastened Poniatowski’s decision to emigrate to the United States. In June of the previous year, it had been written on the pages of The New York Times that his pitiful situation was ‘a striking example of the mutability of affairs’. Unfortunately, the prince survived Napoleon by barely six months, and died prematurely at age 57. He was laid to rest at the cemetery in Chislehurst, within the borders of today’s London.

Stanisław’s illegitimate son had been fascinated with music since childhood. He continues to be dogged by a reputation as a self-taught composer and homegrown singer, but the truth was completely different. Poniatowski trained under Fernando Zeccherini, maestro di cappella at the cathedral and professor at the Academy in Florence; he was an esteemed tenor whose craft was compared with the artistry of Giovanni Battista Rubini, one of Bellini’s favorite singers. He was the author of twelve operas which, while held in contempt by Berlioz, were praised by Rossini and Michele Carafa. Sir George Grove, initiator and editor of the legendary Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, wrote in an appendix to the dictionary’s first edition that Poniatowski’s music is tremendously theatrical and attests to a deep understanding of the potential and limitations of the human voice. Grove praised its originality and flickering spark of true genius – all the more enthusiastically that Poniatowski was also a person of exquisite manners and a favorite at the salons.

His Mass in F, composed in 1867 and dedicated to Luís I Bragança, King of Portugal, was discovered in the collections of the British Library and performed in Poland for the first time in Kraków in 2011 at the initiative of the Association of Polish Music. The work is rooted in the spirit of Rossini’s Petite messe solennelle: it was written barely four years later and scored – as was the original version of the Petite messe – for four soloists, small choir and organ, harmonium or piano. Intimate in expression (which Poniatowski additionally emphasized using the key of F major, which expresses humility and resignation), with fragments of dazzling beauty (the soprano aria ‘Et incarnatus’; the dialogue of the baritone with the choir in the ‘Agnus Dei’; the virtuosic instrumental introductions to the individual movements, bringing to mind the œuvre of Chopin and Liszt), betrays both influences of operatic bel canto style, and attachment to the Italian tradition of vocal musica da chiesa (the polyphonic texture of the final, majestic ‘Amen’ movement). Despite its charm and lightness, Poniatowski’s composition is a typical jewel of mature age: a passionate musical confession of faith in God and the power of love.

It is astounding that from the pen of the same composer came the opera Pierre de Médicis (which in its time scored a real triumph in Paris), the lyrical and expressive Mass in F, and The Yeoman’s Wedding Song, a ballad popular in England that was good-naturedly mocked by P. G. Wodehouse himself in his humoresques. It seems that the uncertain national identity of the Prince of Monte Rotondo also made its mark on his œuvre.

Translated by: Karol Thornton-Remiszewski