Izolda Jasnowłosa i Brunhilda o Białych Dłoniach

Krąg się powoli domyka. W kwietniu minęło dziewięć lat od warszawskiej premiery Lohengrina w koprodukcji z Welsh National Opera – spektaklu, który skomplikowanym zbiegiem okoliczności zaprowadził mnie rok później do Longborough na Tristana. Odkąd znalazłam tam swoją wagnerowską Ziemię Obiecaną, każdy czerwiec przebiega pod znakiem nowej produkcji pod batutą Anthony’ego Negusa. W tym roku LFO wystawiła Zmierzch bogów: przed planowaną pierwotnie na ten sezon, opóźnioną jednak przez pandemię prezentacją wszystkich członów tetralogii. W przyszłym sezonie Bühnenfestspiel odbędzie się trzykrotnie, w ujęciu reżyserskim Amy Lane, która wciąż nie zdołała nas zapoznać z całością swojej koncepcji. Walkirię w roku 2021 przygotowała w wersji półscenicznej, na szczęście dostępnej przez pewien czas na platformie OperaVision – na otarcie łez melomanów i krytyków z zagranicy, pozbawionych możliwości swobodnej podróży do Wielkiej Brytanii.

Kiedy granice się wreszcie otwarły, zaczęłam odwiedzać Wyspy z jeszcze większą intensywnością niż przed pandemią. W ubiegłym sezonie pisałam o wykonaniu Latającego Holendra w Grange Park Opera, jednej z najmłodszych i najbardziej ambitnych „wiejskich oper” w Anglii. Tamto doświadczenie połączyła z Longborough osoba Negusa, który potwierdził swą klasę wybitnego interpretatora spuścizny Wagnera, prowadząc nieoswojony z jego batutą zespół z iście gwiazdorską obsadą głosów solowych. Tym razem trafiła mi się okazja do całkiem innego porównania. W Zmierzchu bogów w Longborough i w nowej inscenizacji Tristana w Grange Park wystąpiły w tym roku obydwie odkryte przez Negusa Izoldy: Lee Bisset, która w najnowszym Ringu w LFO wcieliła się w rolę Brunhildy, oraz Rachel Nicholls, której debiut w Tristanie w 2015 roku okazał się wstępem do międzynarodowej kariery w repertuarze Wagnerowskim i Straussowskim. Dwie znakomite śpiewaczki reprezentujące odrębną, specyficznie brytyjską tradycję śpiewu wagnerowskiego. Dwie opery o końcu świata albo – zależnie od interpretacji – nadziei na zbudowanie tego świata całkiem od nowa. Dwie opowieści o przeistoczeniu za sprawą miłości. Dwa spektakle, na których ostatecznym kształcie w dużej mierze zaważyła osobowość wspomnianych artystek.

W Longborough scena jest maleńka, kanał orkiestrowy naprawdę głęboki, a kontakt z publicznością wyjątkowo intymny. Między innymi z tego powodu najlepsze wrażenia w LFO wyniosłam ze spektakli rozgrywanych w przestrzeni niemal pozbawionej rekwizytów, po mistrzowsku malowanej światłem przez Bena Ormeroda, który wzorem Alphonse’a Appii głosi prymat autora i dramatu, synchronizując intensywność i barwy światła z fabułą i narracją muzyczną dzieła. Amy Lane jest reżyserką bardzo wnikliwą, odsłaniającą w Ringu warstwy znaczeń niedostępne dla większości współczesnych inscenizatorów tetralogii. Niestety, z jej wrażliwością nie zawsze idą w parze pomysły pozostałych uczestników koncepcji teatralnej. Celne tropy interpretacyjne Lane nie znalazły pełnego odzwierciedlenia ani w scenografii Rhiannon Newman Brown – szczęśliwie jednak mniej przeładowanej niż w ubiegłorocznym Zygfrydzie – ani w niezbyt natchnionej reżyserii świateł (Charlie Morgan Jones), ani w zanadto dosłownych projekcjach Tima Baxtera. Najlepsze porozumienie udało się reżyserce osiągnąć z projektantką kostiumów (Emma Ryott), która trafnie odczytała intencję uniwersalizacji mitu, łącząc tradycyjne wyobrażenia o wyglądzie istot przedwiecznych (Norny) z nieco bardziej współczesnym, wciąż jednak nieosadzonym w żadnym konkretnym kontekście ubiorem pozostałych uczestników dramatu.

Zmierzch bogów, LFO. Julian Close (Hunding). Fot. Matthew Williams-Ellis

W koncepcji Amy Lane jest kilka tropów pamiętnych i wstrząsających, począwszy od pomysłu, żeby nić przędziona przez Norny przywoływała na myśl skojarzenia zarówno z ziemską pępowiną, jak i z korzeniami świętego jesionu, porąbanego na rozkaz Wotana przed spodziewanym „zmierzchem bogów”; aż po niezwykłą scenę Snu Hundinga, która w jej ujęciu przybrała postać freudowskiego rozrachunku między ojcem a synem. Większość rozwiązań reżyserskich Lane ma uzasadnienie w dziele i znalazła stosowne odbicie w koncepcji Negusa, który jak zwykle zadbał o logikę muzycznej dramaturgii i utrzymanie wartkiego pulsu narracji bez popadania w patos – czego przykładem choćby Marsz Żałobny Zygfryda, w którym kondukt nie wlókł się noga za nogą, a dźwięki orkiestry już to przelewały się jak fale rozjuszonego Renu, już to strzelały iskrami z płomieni stosu pogrzebowego i nadciągającej pożogi Walhalli. Negus ma niezwykłą umiejętność opowiadania muzyką i angażowania uwagi słuchacza aż do granic hipnozy. Niemniej poziom dbałości o każdy detal faktury, o najdrobniejsze choćby szczegóły brzmienia poszczególnych grup orkiestrowych, o każdą zgłoskę i frazę śpiewanego tekstu – w Zmierzchu bogów przekroczył wszystko, z czym mieliśmy do czynienia w poprzednich częściach Ringu.

To samo dotyczy strony wokalnej spektaklu. Bradley Daley wypadł bardziej przekonująco niż w ubiegłorocznym Zygfrydzie. Jego niezmordowany, odrobinę szorstki, lecz świetnie prowadzony tenor zyskał potężną siłę wyrazu w przedśmiertnym monologu, w którym śpiewak dał odczuć słuchaczom, kim stałby się Zygfryd, gdyby los pozwolił mu dojrzeć do roli godnego partnera Brunhildy. Przez lwią część dramatu na scenie królował fenomenalny Julian Close w roli Hundinga – znakomity aktorsko, w równym jednak stopniu budujący swą postać środkami czysto muzycznymi. Złowieszczy majestat kryje się w samym głosie Close’a, czarnym jak noc na nowiu, a zarazem uwodzicielsko pięknym, wywiedzionym z najlepszej tradycji potężnych i mrocznych basów niemieckich w rodzaju Gottloba Fricka. Podobnej siły brakuje w śpiewie Freddiego Tonga, co dyrygent i reżyserka obrócili tylko na jego korzyść w dojmującej scenie Snu Hundinga, umiejętnie kontrastując upokorzenie Alberyka z burzą sprzecznych uczuć targających jego synem. Mnóstwo żaru w krótką partię Waltrauty tchnęła niezawodna Catherine Carby, pamiętna Brangena z Tristana w 2015 roku. Znakomicie dobraną parę naiwnych Gibichungów stworzyli Laure Meloy (Gutruna), dysponująca sopranem krągłym i bardzo pewnym intonacyjnie, oraz Benedict Nelson (Gunther), śpiewak obdarzony urodziwym, inteligentnie prowadzonym barytonem i dużym instynktem dramatycznym, dzięki któremu udało mu się stworzyć wielowymiarową postać, w finale przejętą autentycznym wstydem i pogardą dla własnej słabości. Osobne słowa uznania należą się dwóm doskonale zestrojonym ansamblom – Norn (Mae Heydorn, Harriet Williams i Katie Lowe) oraz Cór Renu (Mari Wyn Williams, Rebecca Afonwy-Jones i Katie Stevenson) – oraz Chórowi Festiwalowemu, wzmocnionemu przez członków Longborough’s Community Chorus.

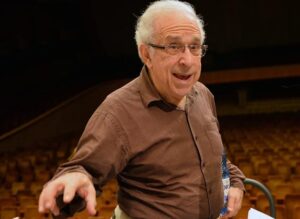

Zmierzch bogów, LFO. Lee Bisset (Brunhilda). Fot. Matthew Williams-Ellis

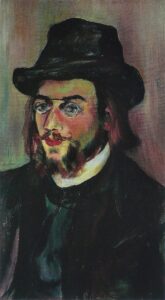

Wielką rolę Brunhildy w wykonaniu Lee Bisset zostawiłam sobie na koniec. Ta wspaniała aktorka i moim zdaniem wciąż nie w pełni doceniona śpiewaczka powinna częściej pojawiać się na scenach – choćby po to, by uzmysłowić krytykom, że wytykane jej czasem zbyt szerokie wibrato i ścieśnione góry nie są wynikiem zmęczenia głosu, tylko wręcz przeciwnie: niedostatecznego ośpiewania. Przekonałam się już w grudniu w Inverness, że drobne niedociągnięcia techniczne w jej śpiewie odchodzą powoli w przeszłość, odsłaniając niewiarygodną urodę ciemnego, a przy tym zaskakująco ciepłego sopranu. W Zmierzchu bogów pod batutą Negusa potencjał wokalny Bisset szedł w parze z mądrością interpretacji. Brunhilda z każdą kolejną kwestią – w sposób niemal namacalny – zyskiwała coraz większą świadomość roli, jaką wyznaczył jej los w nieuchronnym końcu starego porządku świata. Pełnię tego olśnienia osiągnęła w finałowym monologu. Większość współczesnych sopranów wagnerowskich wkłada wszelkie siły w samo zaśpiewanie tej potężnej sceny. Bisset zdołała ją zróżnicować: gestem, mimiką, całą paletą odcieni głosu, innym tonem przemawiając do Gibichungów, innym oskarżając Wotana, innym roztrząsając sens i przyczynę śmierci Zygfryda, by ostatecznie zjednoczyć się z nim w ekstatycznych słowach „Selig grüsst dich dein Weib”. Przeistoczenie Brunhildy w takim ujęciu znacznie dobitniej przemawia do wyobraźni niż jakiekolwiek przeistoczenie Izoldy – zwłaszcza dopełnione tak malarską interpretacją zagłady Pierścienia i ruiny Walhalli. Nic dziwnego, że po wybrzmieniu ostatniego akordu w orkiestrze na widowni zapadła kompletna cisza, dopiero po minucie przerwana wybuchem frenetycznego aplauzu. Po takim zmierzchu świt nadchodzi nieprędko.

Nie pierwsze to zresztą takie doświadczenie w Longborough. Przypuszczam, że nie dożyję już Tristana na miarę premiery i późniejszego o dwa lata wznowienia w LFO – pod batutą Negusa i w reżyserii Carmen Jakobi. Wciąż jednak nie tracę nadziei: w każdym sezonie staram się obejrzeć i usłyszeć przynajmniej dwie nowe produkcje tej opery. I muszę przyznać, że tegoroczny Tristan w Grange Park Opera pod względem muzycznym okazał się jednym z najlepszych.

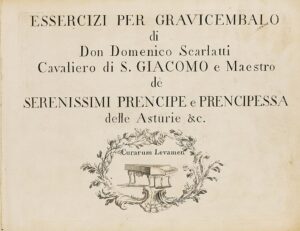

Gorzej poszło z warstwą teatralną, mimo że Charles Edwards jest artystą bardzo wszechstronnym i ma w dorobku imponującą liczbę realizacji operowych – przede wszystkim jako scenograf, ale też reżyser świateł i twórca spektakli autorskich, w których odpowiadał za całość koncepcji inscenizacyjnej. Szczerze mówiąc, miałabym kłopot z wyodrębnieniem charakterystycznych elementów jego stylu, który ulega bezustannym przemianom – jak sądzę, w dużej mierze zależnym od bieżącego zapotrzebowania na konkretną estetykę i wątki interpretacyjne. Podziwiałam w Warszawie jego znakomitą scenografię do Katii Kabanowej w reżyserii Davida Aldena, ciepło pisałam o spójnej koncepcji plastycznej cyklu Little Greats w Opera North, gdzie Edwards zajął się także wyreżyserowaniem Pajaców, włos mi na głowie dęba stanął, gdy zobaczyłam, jak zaśmiecił scenę w kuriozalnej produkcji Fausta Gounoda w Teatrze Wielkim w Poznaniu, firmowanej nazwiskiem Karoliny Sofulak. W swoim Tristanie dla Grange Park poszedł modnym tropem biograficznym, sugerując – poniekąd słusznie – że Wagner komponował operę na fali miłosnych uniesień wobec Matyldy von Wesendonck, zapominając jednak, że wpadł na ten pomysł kilka lat wcześniej i nie pod wpływem uczucia do pięknej żony kupca jedwabnego, tylko lektury Schopenhauera. Przestrzeń sceniczną zabałaganił prawie jak w Poznaniu, stylizując ją ni to na wnętrze willi Wesendoncków w Zurychu, ni to na komnaty baśniowego zamku Neuschweinstein, i zamykając dekoracjami, które wbrew szumnym i błędnym zapowiedziom nie nawiązywały do premiery Tristana, tylko do późniejszych przedstawień w Bayreuth, z których pierwsze odbyło się trzy lata po śmierci Wagnera. Właśnie do tej produkcji, wyreżyserowanej przez samą Cosimę, scenografię zaprojektował Max Brückner. Na tym jednak Edwards nie poprzestał: w III akcie wykorzystał projekt Kurta Söhnleina do słynnej inscenizacji Siegfrieda Wagnera z 1927 roku.

Tristan i Izolda, GPO. David Stout (Kurwenal). Fot. Marc Brenner

Tak to bywa, kiedy reżyser nie zleci porządnego researchu przed zabraniem się do roboty. Zamiast odważnej reinterpretacji wyszła sztampa, powielająca obiegowe mity na temat okoliczności powstania dzieła i jego monachijskiej prapremiery. Edwards powierzył reżyserię świateł Timowi Mitchellowi, który skąpał to panoptikum w barwach kojarzących się bardziej z horrorem klasy B niż z historią dwojga złączonych śmiercią kochanków. Sytuację odrobinę ratowały stylowe kostiumy Gabrielle Dalton, ale i tak w miejsce symbolu i metafizyki dostaliśmy historię pospolitej zdrady małżeńskiej. Na dodatek z finałem niebezpiecznie przypominającym zakończenie frankfurckiej inscenizacji Kathariny Thomy sprzed trzech lat, gdzie miłosne przemienienie Izoldy, podobnie jak u Edwardsa, odbyło się bez Tristana, odesłanego wcześniej za kulisy.

W sukurs Tristanowi przyszedł sam Wagner, a ściślej jego muzyka – w ponadprzeciętnym, chwilami wręcz porywającym wykonaniu. Całość poprowadził Stephen Barlow, pewnie i elegancko, podchodząc jednak do materii Wagnerowskiej całkiem inaczej niż Negus, który buduje dramaturgię Tristana metodą naprzemiennych napięć i odprężeń. U Barlowa narracja muzyczna przebiega po krzywej wznoszącej się powoli, lecz nieubłaganie, zwłaszcza w ogólnym planie agogicznym. Z początku mnie to nużyło, później zaczęłam doceniać, tym bardziej, że Gascoigne Orchestra grała pod jego batutą precyzyjnie, pięknie wyważonym dźwiękiem, z doskonałym wyczuciem proporcji między kanałem a sceną.

W roli Tristana w Grange Park zadebiutował walijski tenor Gwyn Hughes Jones, kojarzony od lat przede wszystkim z repertuarem włoskim. Jones dysponuje miękkim głosem o pięknej, złocistej barwie, znakomitą techniką i cenną umiejętnością rozłożenia sił na cały spektakl. Jego melancholijny, ujmujący liryzmem Tristan być może nie przypadłby do gustu tak licznym dziś zwolennikom obsadzania w tej partii stentorowych Heldentenorów, myślę jednak, że zyskałby uznanie samego Wagnera, który cenił w śpiewakach przede wszystkim inteligencję i wyczucie muzycznej dramaturgii. Obydwu tych cech nie zabrakło Jonesowi w wielkim monologu z III aktu, od pierwszych taktów spowitym w mrok upragnionej nocy śmierci. U boku rannego bohatera czuwał jeden z najwspanialszych Kurwenali, jakich słyszałam w ostatnich sezonach – David Stout, który z taką wrażliwością i z tak mądrze prowadzonym, doskonale rozwiniętym w dole skali barytonem mógłby już wkrótce zacząć rozważać debiut w którejś z cięższych partii wagnerowskich. Na tym nie koniec olśnień. Matthew Rose dostarczył mi kolejnego argumentu na potwierdzenie tezy, że w finale II aktu Tristana Wagner sięgnął najbliżej sedna antycznej tragedii. W fenomenalnie zinterpretowanym przez Rose’a monologu Króla Marka nie było ani furii, ani wstydu: tylko spokojna, pełna goryczy konstatacja faktu, którego nie da się już odwrócić. Myślę, że angielski bas świadomie podbarwił swój śpiew odrobinę verdiowskim odcieniem: nie tylko ja zaczęłam się zastanawiać nad ewentualnym pokrewieństwem Don Carlosa z wcześniejszym o kilka lat Tristanem. Równie wybitną odtwórczynię zyskała Brangena – w osobie Christine Rice, jednej z najznakomitszych mezzosopranistek swego pokolenia, a zarazem świetnej aktorki. W pomniejszych rolach dobrze wypadli Sam Utley (Pasterz) i Thomas Isherwood (Sternik). Na osobne wyrazy uznania zasłużył Mark Le Brocq, obsadzony w roli, w której Edwards scalił w jedno postaci Melota i Młodego Żeglarza. Pomysł bez sensu, wykonanie przepyszne: w pamięć zapadło mi zwłaszcza szyderstwo przebijające z żeglarskiej piosenki o „Irische Maid, du wilde, minnige Maid”, w pełni uzasadniające późniejszy wybuch wściekłości Izoldy.

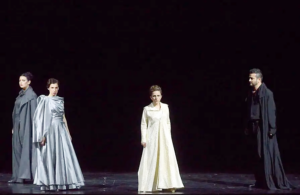

Tristan i Izolda, GPO. Rachel Nicholls (Izolda). Fot. Marc Brenner

W tę zaś, po raz kolejny w swojej karierze, wcieliła się Rachel Nicholls, śpiewaczka niezwykle muzykalna, obdarzona żywym temperamentem scenicznym i wyrazistą osobowością. Głos ma równie pełny jak Bisset, ale ostrzejszy, bardziej dziewczęcy, skrzący się odmiennymi barwami. W jej gniewie jest więcej frustracji i buntu, w okazywanych przez nią uczuciach – więcej porywczego żaru niż spokojnej, intymnej bliskości. W inscenizacji Edwardsa przyszło odgrywać jej rolę niespełnionej mieszczki, która dopiero w finałowym przemienieniu docenia potencjał swej kobiecości. Nicholls celnie odczytała ten trop jako zwrot w stronę modernizmu, także muzycznego. Swoją interpretację nasyciła niedawnymi doświadczeniami w repertuarze Straussowskim, budując postać chwilami bardziej ludzką niż Tristan, a w każdym razie lepiej zrozumiałą dla współczesnego odbiorcy. Stworzyła Izoldę pamiętną, jak sądzę, także własnym wysiłkiem, bo w jej śpiewie i grze aktorskiej dopatrzyłam się wielu gestów zapamiętanych z wcześniejszych inscenizacji.

A my tu narzekamy na zmierzch wagnerowskich bożyszcz. Może czas już podpalić tę zmurszałą Walhallę i zacząć wszystko od nowa?