Zakhor is no ordinary memory. It is an imperative to remember, a duty of every Jew, repeated in daily prayers – an absolute imperative, preceding knowledge, preceding comprehension. If we tried to explain it, using some mundane example, zakhor would be the cry of “Stop! Don’t touch it!” to a child marching confidently towards a bucket of boiling water. Remember before you comprehend. One day you will understand why you cannot put your hand into boiling water. In such an approach memory becomes an internalised norm imposed from outside. As years go by and new experiences are acquired, it will turn into an autonomous norm, lived through, understood and observed voluntarily. Since the destruction of the Second Temple and beginning of the diaspora zakhor has constituted the Jewish identity: treating history as a myth that helps to give sense to the present. History relived again and again is a guarantee of existence. If you forget, if you do not instil it in your sons – you will lose the way to the land which the Lord “swore to your ancestors”.

In this sense Weinberg’s The Passenger is an opera about memory. It is not about an all-consuming memory of the wrongs suffered, as Zofia Posmysz feared, interpreting Marta’s final monologue – featuring a fragment from a poem by Paul Éluard – as being against the Christian duty to forgive. Contrary to the doubts expressed by some Jewish communities after the American premiere of the work, The Passenger is indeed an opera about the Holocaust, although there are virtually no Jews in the libretto. They are not there, because Weinberg wrote the opera in circumstances precluding any direct references to the tragedy of the Shoah.

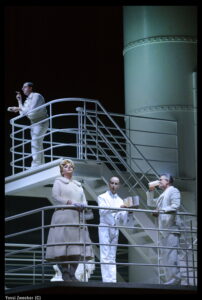

Photo: Yossi Zwecker

As early as in 1944, at a time of the Red Army’s impressive victories over the Third Reich, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee lost its raison d’être, having been established two years previously by the NKVD – mainly to win support of the Jewish diaspora for the USSR’s fight against Nazi Germany. Shortly after the war the Committee’s activities began to be denounced as “nationalistic” and “Zionistic”. January 1948 was marked by the death of the composer’s father-in-law: the chairman of the Committee, Solomon Mikhoels, an eminent actor and director, artistic director of the Moscow Jewish Theatre, who shortly after the founding of the Committee set out, on Stalin’s initiative, on a long overseas journey, during which he managed to persuade American Jews to allocate funds for the purchase of one thousand planes, five hundred tanks as well as food and other necessary provisions for the Soviet Army. The bodies of Michoels and the theatre critic Vladimir Golubov-Potapov were found by factory workers on their way to their morning shift. According to the investigators’ report, commissioned by Ivan Serov, future head of the KGB, the death “resulted from [the victims’] having been run over by a heavy goods vehicle. The deceased had all their ribs broken and pulmonary tissue torn, Michoels – broken spine, Golubov-Potapov – hip bone. (…) No data suggesting that Michoels and Golubov-Potapov had died as a result of a cause other than a hit-and-run accident were found in the course of the investigation”.

By the death of Stalin hundreds of intellectuals and artists of Jewish origin had been “liquidated” as a result of massive repressions. After the dictator’s death even his fierce opponent Nikita Khrushchev did not include his murderous provocations in violations of the “Leninist principles of the revolutionary rule of law”. The Passenger was written in the shadow of a new wave of Soviet anti-Semitism which was a response to Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War. A young radio engineer, Boris Kochubievsky, who sent a letter to Brezhnev declaring that he wanted to settle in the Jewish state, thus fulfilling the dream of hundreds of generations preceding him, was summoned to a KGB office and without any hearing was locked in psychiatric hospital. There began a smear campaign against real and alleged “Zionists”, with its repercussions affecting nearly all Jews in the USSR.

At that time Weinberg was locked in a painful battle with manifestations of memory and oblivion. In 1966 he left Moscow for the first time since the war – joining a delegation of Soviet composers going to the Warsaw Autumn Festival. His former colleagues from the conservatoire pretended they did not recognise him. He himself did not recognise Warsaw from his youthful memories. He did not want to return again. He came back from Poland with the melody of a recently discovered song to Mary, Angelus ad Virginem missus, echoed in the figure of the prisoner Bronka. In his opera only she has an unequivocally “Polish” sonic identity. In Act II Marta – the eponymous passenger from cabin 45 – uses the musical language of a Bessarabian shtetl, from which Weinberg’s future parents escaped. Debased, Tadeusz plays the chaconne from Bach’s Partita in D minor before an SS man, not only in an act of artistic defiance, but also as a tribute to the thousands of murdered Jewish violinists.

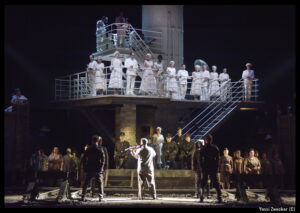

Photo: Yossi Zwecker

What many contemporary critics see as trivialisation of Zofia Posnysz’s message was, in fact, an attempt to outmanoeuvre Soviet censorship by Weinberg and his librettist Alexander Medvedev. It failed. In 1968 the opera was removed from the repertoire of Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, having been accused of “abstract humanism”, which in the Soviet newspeak meant that the spectators could see The Passenger as a veiled manifesto of Zionism or an allegory of the Gulag. Weinberg did not live to see the premiere: he died in 1996, ten years before a concert performance of his beloved composition. Its subsequent fate has been mentioned many times, especially in the context of David Pountney’s Warsaw production, which reached Teatr Wielki-Polish National Opera in October 2010, less than three months after the stage premiere in Bregenz. I wrote at the time that in Poland, which still could not shake off the memory of the Holocaust, it was difficult to accept a naturalistic, although at times “aestheticising” vision of Auschwitz. That we would prefer to transform this tragedy into a symbol or, even better, to remain silent about it.

Yet Poles treat the Shoah in historiographic terms, as a tragedy that has not been worked through, but fortunately is a thing of the past. The Jews experience the Holocaust as if it happened yesterday; they cultivate its memory in order to continue to live and to survive. They do not want any allegories. They want an experience. That is why I was so looking forward to the Israeli premiere of The Passenger, which took place – after years of efforts and thanks to considerable help from the Adam Mickiewicz Institute – at the New Israeli Opera in Tel Aviv, in Pountney’s now legendary staging. I had heard that during the preparations for the premiere the musicians, especially the singers, reacted very emotionally, entered into their roles with abandon, became their characters. The result exceeded all my expectations. The orchestra – conducted by Steven Mercurio, who had conducted The Passenger several times in the United States, for example at the Michigan Opera Theatre in Detroit – did have its weak moments, but there were miracles happening on stage. This was undoubtedly largely due to the three protagonists (Adrienn Miksch as Marta, Daved Karanas as Liza and David Danholt as Walter), who had triumphed in earlier productions of Weinberg’s opera. Yet the old troupers had managed to share their experience with their Israeli colleagues so effectively that already in the middle of the first act I could no longer sense who had been singing their roles for years and who was making their debut in roles which often required them facing the memory of the tragedy of their own ancestors. Applauded thunderously in the middle of Act II, Alla Vasilevitsky (Katia) is a recent graduate of the Meitar Opera Studio, a programme for young artists affiliated with the local opera company. Zlata Khershberg was harrowing Bronka. After the final performance the artist hopped on a plane and flew to Warsaw to take part in the Stanisław Moniuszko competition. The audience gave the premiere cast a standing ovation. There were tears. There were questions. There were long conversations after leaving the theatre.

Photo: Yossi Zwecker

In recent years I have heard a lot of Weinberg’s music and seen a lot of productions of The Passenger. Not once did it cross my mind that Pountney’s staging – greeted with mixed feelings in Poland nearly a decade ago – would grow so much, would get new meanings, would turn out to be a vehicle of history tangled up in the present. One day after the Israeli premiere, a few hours before Yom HaShoah – the Holocaust Remembrance Day, which begins at sunset and since 1951 has been celebrated on the 27th day of the month of Nisan – I took advantage of the courtesy of the company’s management and sneaked onto the empty stage with sets ready for subsequent performances in the run. I walked along the theatrical railway tracks leading to the Gate of Death. I stopped to look at the remains of Tadeusz’s broken violin. I remembered. I did not take it in yet. Perhaps one day I will understand.

Translated by: Anna Kijak

Original article available at: https://www.tygodnikpowszechny.pl/pasazerka-z-bydlecych-wagonow-158779