Dom Wahnfried nazwany

Minęło prawie dziesięć lat, a wciąż mam poczucie, że jednym z najbardziej inspirujących przedsięwzięć, z jakimi zetknęłam się w swojej karierze krytycznej, był Wagnerowski Pierścień Nibelunga w Karlsruhe – zrealizowany z inicjatywy Petera Spuhlera, ówczesnego dyrektora Badisches Staatstheater, siłami czterech reżyserów, po jednym na każdą część cyklu, i uzupełniony nową operą Wahnfried, zamówioną specjalnie na tę okazję u izraelsko-amerykańskiego kompozytora Avnera Dormana. Pisałam wtedy, że teatr przy Hermann-Levi-Platz – nazwanym na cześć potomka słynnego rodu rabinackiego, kapelmistrza opery dworskiej w Karslruhe i wielkiego admiratora Wagnera, który po rozlicznych perypetiach powierzył mu premierę swego Parsifala – przetrze reżyserom szlak teatralny do Bayreuth. I rzeczywiście: z czwórki „młodych zdolnych” na Zielone Wzgórze dotarło już trzech, a Lohengrin w ujęciu Yuvala Sharona doczeka się w tym sezonie bezprecedensowego powrotu na scenę Festspielhaus.

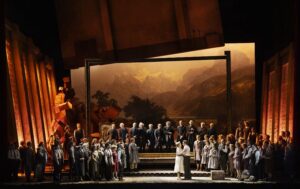

Trudno o lepsze potwierdzenie tezy o potrzebie oderwania dzieła od twórcy niż bilans dyrekcji Spuhlera w Karlsruhe. Jego kadencja – wyjątkowo udana pod względem artystycznym – zakończyła się przedwcześnie i burzliwie, po gwałtownych protestach przeciwko autorytarnym metodom rządzenia zespołem. Ring czterech reżyserów mimo to przeszedł do historii teatru, świetne recenzje zebrał też Wahnfried – dopracowany w najdrobniejszych szczegółach przez wszystkich zaangażowanych w przedsięwzięcie twórców i artystów, począwszy od kompozytora i autorów angielsko-niemieckiego libretta, Lutza Hübnera i Sarah Nemitz; przez dyrygenta Justina Browna i pieczołowicie dobraną obsadę, w której znalazło się kilku solistów Pierścienia pod jego batutą; skończywszy na ekipie realizatorów, na czele z Keithem Warnerem.

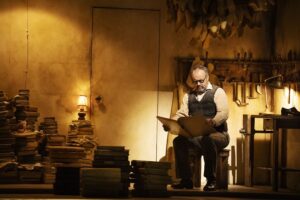

Mark Le Brocq (Houston Stewart Chamberlain). Fot. Matthew Williams-Ellis

Tytuł opery Dormana nawiązuje do willi w Bayreuth, w której Wagner spędził ostatnie lata życia i którą nazwał Wahnfried – ku wielkiej uciesze ówczesnych mieszkańców miasta, kojarzących słowo „Wahn” głównie z szaleństwem i urojeniem. Tymczasem kompozytor miał na myśli Schopenhauerowski szał twórczy i azyl, gdzie można zaznać od niego wytchnienia. Zapewne sam nie przewidział, że Haus Wahnfried przemieni się z czasem w upiorne mauzoleum, siedzibę zwyrodniałego kultu jego osoby i twórczości, kreowanego przez zastygłą w żałobie wdowę Cosimę i jej coraz dziwniejszych akolitów: wśród nich wyrwanego z korzeniami z własnej kultury Houstona Stewarta Chamberlaina, zwolennika rasistowskiej myśli Arthura de Gobineau i żarliwego propagatora ideologii volkistowskiej, która zdaniem wielu wywarła zasadniczy wpływ na rozwój późniejszej doktryny nazizmu.

Protagonistą opery Dormana jest właśnie Chamberlain – zgodnie z intencją współtwórców przedsięwzięcia, które przypadło na czas historycznych rozliczeń klanu z Bayreuth, zapoczątkowanych kilka lat przed jubileuszem dwusetlecia urodzin kompozytora. Wahnfried był z założenia czymś w rodzaju divertissement między kolejnymi prezentacjami Pierścienia w Karlsruhe: twórczą impresją na temat „niebezpiecznych związków” rodziny Wagnera, równoległą do wielu ówczesnych inicjatyw edukacyjnych, na czele ze słynną, częściowo wciąż dostępną na Zielonym Wzgórzu wystawą „Verstummte Stimmen”, oraz filmem dokumentalnym Wagner & Me, z udziałem brytyjskiego aktora, pisarza i wagneryty Stephena Fry’a.

Wahnfried okazał się impresją tym ciekawszą, że przefiltrowaną przez doświadczenia i wrażliwość zaledwie czterdziestoletniego twórcy wychowanego w Izraelu, gdzie muzyka Wagnera wciąż pozostaje tabu, niemożliwym do przełamania nawet przez wybitnych artystów pochodzenia żydowskiego. Być może dlatego Dorman nie wpadł w pułapkę wagnerowskiego pastiszu, tworząc swą pierwszą operę w duchu postmodernistycznego eklektyzmu – z mnóstwem odniesień do form i gatunków z przeszłości, niby dwuaktową, w rzeczywistości złożoną z kilkunastu odrębnych epizodów, zestawionych metodą niemal filmowego kontrastu planów muzycznych. Dorman jest bardzo sprawnym warsztatowo polistylistą. Klimat dźwiękowy utworu, oparty na wyrazistych strukturach melodycznych i ostinatowej, iście szostakowiczowskiej rytmice, buduje z nawiązań do jazzu, salonowych walców, marszów wojskowych, weimarskiego kabaretu, pojedynczych lejtmotywów z oper Wagnera, muzyki klezmerskiej, strzępów chorału protestanckiego. Partie solowe oscylują między stylem deklamacyjnym a przejmującym liryzmem (wspaniały monolog Siegfrieda Wagnera na początku II aktu), w scenach zbiorowych stapiając się idealnie z brzmieniem chóru i skrzącą się barwami warstwą orkiestrową.

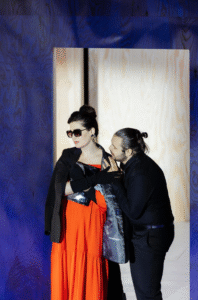

Pośrodku: Susan Bullock (Cosima Wagner). Fot. Matthew Williams-Ellis

Muzyka Wahnfried – wyrafinowana, a zarazem przystępna – ma w sobie coś nieodparcie „amerykańskiego”. Wielu krytykom przywodzi na myśl asocjacje z Johnem Adamsem, mnie kojarzy się raczej z Johnem Corigliano i typową dla jego twórczości fuzją stylów: niewolną od groteski i czarnego humoru, lawirującą między realizmem a światem ułudy, skutecznie burzącą konwencję, jak w odrobinę dziś zapomnianej operze Duchy Wersalu. Dorman i jego libreciści zbyt często jednak odwołują się do stereotypów: Chamberlain został żarliwym wagnerytą już w latach siedemdziesiątych XIX wieku; pierwszy raz gościł w Wahnfried dopiero w 1888 roku, pięć lat po śmierci uwielbianego kompozytora; dopiero wtedy dołączył do Bayreuther Kreis, w którym ziarno volkistowskiego nacjonalizmu i nowej, rasistowskiej odmiany antysemityzmu zdążył już posiać baron Hans von Wolzogen – człowiek, którego sam Wagner zaprosił do redagowania miesięcznika „Bayreuther Blätter” i wkrótce potem gorzko tego pożałował. Historia odsunięcia od wagnerowskiego dziedzictwa Isolde, pierwszego owocu miłości Cosimy i Richarda, jest znacznie bardziej tragiczna i wielowątkowa: Cosima sama żyła z piętnem nieślubnego dziecka Liszta, sprawy „skomplikował” jej ówczesny mąż Hans von Bülow, uznając ojcostwo Isolde. Na jej odrzuceniu przez matkę zaważyły też ówczesne konwenanse, piętnujące małżeństwa utrzymywane przez żonę – a to właśnie było udziałem Isolde, która wyszła za biednego jak mysz kościelna dyrygenta Fritza Beidlera. Chamberlain sam smalił cholewki do Isolde: jego późniejsze małżeństwo z Evą von Bülow, drugą córką Wagnera, było efektem wyrachowanej kalkulacji. O przedwczesnym zgonie Isolde Cosima dowiedziała się przypadkiem dziesięć lat po fakcie – i niecały rok przed własną śmiercią. Co jednak najważniejsze, zarówno Cosima, jak i Houston Stewart Chamberlain zmarli przed dojściem Hitlera do władzy, a główną winowajczynią późniejszych związków dyktatora z Bayreuth była naiwna i niezbyt inteligentna Winifred, której poczynania zasługują na osobną operę.

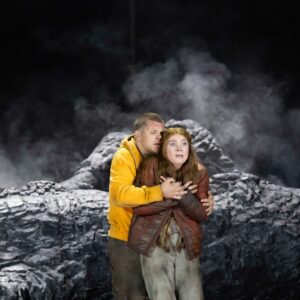

Narracyjne uproszczenia i niedostatki głębi psychologicznej Wahnfried zniwelowano w Karlsruhe udziałem śpiewaków wzbudzających bezpośrednie skojarzenia ze złożonymi postaciami Ringu. W prześladującą Chamberlaina zjawę Wagnera wcielił się wykonawca równie dwuznacznej postaci Alberyka. Rozdarty między miłością do kompozytora a koniecznością znoszenia jego antysemickich docinków Hermann Levi zyskał odtwórcę w osobie ówczesnego interpretatora roli Wotana.

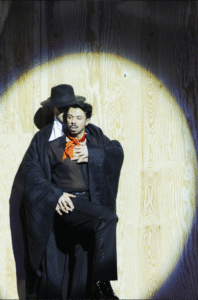

Polly Graham, reżyserka spektaklu z Longborough, poszła innym tropem: wdała się w dialog z prapremierową koncepcją Keitha Warnera, chwilami się z nią kłócąc, chwilami rafinując pomysły brytyjskiego inscenizatora. Groteskową figurę Chamberlaina świadomie przystawiła do rzeczywistości – Mark Le Brocq jest znacznie bliższy historycznemu pierwowzorowi postaci niż Matthias Wohlbrecht, kreujący tę rolę w Karlsruhe. Zachowała wodewilowo-kabaretowy nastrój części epizodów, angażując do przedsięwzięcia między innymi znakomitą tancerkę i artystkę cyrkową Tamzin Moulding w roli Akrobatki. Wagner-Dämona – w ujęciu Warnera przywodzącego na myśl skojarzenia z Jackiem Napierem z Burtonowskiego Batmana – przeistoczyła w zielonego błazna, dżokera wyciąganego z talii w kolejnych rozdaniach kart historii. Ucznia Mistrza – w domyśle Hitlera, ucharakteryzowanego przez reżysera prapremiery na dyktatora z filmu Chaplina – wprowadziła na scenę jako weterana Wielkiej Wojny, w mundurze przyozdobionym pomponami klauna. We współpracy ze scenografem Maxem Johnsem i projektantką kostiumów Anishą Fields przekonująco oddała upiorną atmosferę bayreuckiego klanu – sterowanych przez Cosimę manipulatorów, którzy wykoślawili i tak z dzisiejszego punktu widzenia kontrowersyjne idee kompozytora.

Oskar McCarthy (Wagner-Dämon). Fot Matthew Williams-Ellis

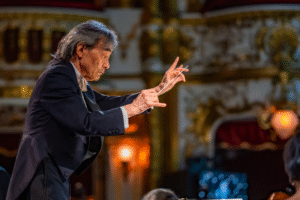

Pod względem muzycznym Wahnfried z Longborough w pełni dorównał spektaklowi z Karlsruhe. Wyrazy szczególnego uznania należą się Le Brocqowi za fenomenalny występ w roli Chamberlaina, wykraczający daleko poza pierwotne ramy partii charakterystycznej. Nie sposób pominąć mrożącej krew w żyłach interpretacji postaci Cosimy przez zaprawioną w wagnerowskich bojach Susan Bullock, która u schyłku kariery zdołała przekuć swe nieuchronne słabości w atuty godne najlepszych scen świata; popisu znakomitej techniki w wydaniu Alexandry Lowe, dysponującej sopranem niezwykle urodziwym, ekspresyjnym i pewnym intonacyjnie, co było do udowodnienia w podwójnej roli Isolde oraz Winifred; oraz wzruszającego ujęcia Siegfrieda Wagnera przez Andrew Wattsa, który wykreował tę partię w Karlsruhe – choć jego kontratenor od tamtej pory zmatowiał i zubożał w alikwoty, zdecydowanie zyskał na sile wyrazu. Świetnie sprawili się też sopranistka Meeta Raval (jako Anna i Eva, czyli kolejne żony Chamberlaina); Adrian Dwyer, pamiętny Mime z Pierścienia pod batutą Negusa, tym razem w złowieszczej roli Ucznia Mistrza; debiutujący w LFO baryton Edmund Danon (jako żywy i martwy Hermann Levi); oraz przybywający z nieco innego porządku Oskar McCarthy w barytonowej partii Wagner-Dämona – wszechstronny śpiewak, aktor i performer, który pewne niedostatki techniki wokalnej wynagrodził z nawiązką rzemiosłem teatralnym. Na życzliwą wzmiankę zasłużył też kubańsko-francuski bas-baryton Antoin Herrera-López Kessel w rolach cesarza Wilhelma II i anarchisty Bakunina. Nie zawiódł oczekiwań liczny jak na tę scenę zespół chórzystów, powiększony o kilkanaścioro członków Longborough Community Chorus. Całość poprowadził Justin Brown, powtarzając swój sukces z Karlsruhe i po raz kolejny dowodząc bywalcom LFO, że jest nie tylko skutecznym dyrygentem, lecz przede wszystkim bardzo wrażliwym muzykiem.

Brytyjska premiera Wahnfried, mimo wspomnianych już niedociągnięć utworu doskonale przyjęta przez krytykę i publiczność, okazała się przedsięwzięciem ważnym i potrzebnym. Tym istotniejszym, że za jego realizację wzięła się LFO – teatr stworzony z czystej i bezinteresownej miłości do Wagnera, udowadniający raz po raz, że dba o jego spuściznę mądrzej, niż błądzący po wielu manowcach bayreuccy spadkobiercy. Dlatego dziwią mnie pojedyncze głosy, jakoby wystawienie opery Dormana w „angielskim Bayreuth” było aktem straceńczej odwagi, inicjatywą obarczoną ryzykiem przewartościowania dotychczasowych osiągnięć wiejskiej opery w Gloucestershire. Dlatego zaniepokoił mnie zamieszczony w programie esej, którego autor, Michael Spitzer – być może w najlepszej woli – dopuścił się manipulacji w drugą stronę. Świat znów się pogrąża w piekle hipokryzji, znów odradzają się ideologie, które po klęsce Hitlera miały na zawsze odejść w niebyt. Lepiej więc nie powtarzać dawno skompromitowanej legendy o porcelanowych małpach Mosesa Mendelssohna, dziadka kompozytora Feliksa – upokarzającym zakupie, którego filozof musiał dokonać, by zyskać pozwolenie na małżeństwo. Spitzer powiela wyświechtaną clichée, jakoby figurki ze zbioru Mendelssohnów były przykładem tak zwanej Judenporzellan, wykupywanej przez Żydów pod przymusem, w zamian za prawo do założenia rodziny i posiadania legalnego potomstwa. Owszem, Fryderyk Wielki ogłosił to haniebne zarządzenie – jedno z wielu, które miały zwiększyć sprzedaż wyrobów jego berlińskiej manufaktury – ale dopiero w 1769 roku, kiedy Moses był już dawno żonaty. Mało tego, ten sam Fryderyk nadał mu sześć lat wcześniej status Schutzjude, chroniący uczonego przed prześladowaniami, które rzeczywiście dotykały jego uboższych i mniej uprzywilejowanych pobratymców – czyli w praktyce większość społeczności żydowskiej w Prusach. Jakkolwiek figurki z kolekcji Mendelssohnów wydają się dziś szkaradne, w czasach Mosesa uchodziły za symbol luksusu i zamożności. Feliks nie mógł więc traktować odziedziczonej po dziadku pamiątki jako „rasistowskiego memento mori”. Cała ta opowieść jest anachronicznym konstruktem, odrzuconym przez badaczy niemal pół wieku temu.

Co nie oznacza, że w czasach Wagnera nie było w Niemczech antysemityzmu. Co nie oznacza, że Wagner nie był antysemitą. Nie oznacza wreszcie, że Chamberlain nie wlał w ten zaczyn rasistowskiej trucizny – z katastrofalnym skutkiem, o czym coraz częściej zdarza się nam zapominać. Żeby wprowadzić odbiorców w dzieło Dormana, nie wolno manipulować historią. Trzeba szukać prawdy, a ta wcale nie leży pośrodku. „Prawda leży tam, gdzie leży”, jak mawiał Władysław Bartoszewski, członek prezydium Żegoty i Sprawiedliwy wśród Narodów Świata. Człowiek, który doskonale rozumiał sens zwrotu „niedźwiedzia przysługa”.