Czekając z niepokojem, ale też z nadzieją na zapowiadane od dawna zmiany na stanowiskach dyrektorskich w Teatrze Wielkim-Operze Narodowej, bacznie obserwuję poczynania naszych południowych sąsiadów. Zarówno w Polsce, jak i w Czechach mocno trzymają się zwolennicy powierzania funkcji kierowniczych w instytucjach narodowych rodzimym artystom i menedżerom. Na tym jednak podobieństwa się kończą. W TW-ON dawno już porzucono model teatru repertuarowego, dysponującego stałym zespołem solistów – co moim zdaniem stawia pod znakiem zapytania zasadność nazywania tej sceny „Operą Narodową”. W dwóch najważniejszych teatrach czeskich – Narodowym w Pradze i Narodowym w Brnie – wszystko wygląda znacznie bardziej spójnie. Obydwa działają w formule wielkiej machiny organizacyjnej, obejmującej wszelkie rodzaje teatru, zarządzanej przez dyrektora naczelnego, któremu podlegają dyrektorzy artystyczni i administracyjni poszczególnych „oddziałów”. W obu miastach w struktury teatru narodowego wchodzi więcej niż jedna scena operowa. Repertuar jest potężny i wyraźnie nastawiony na pielęgnowanie rodzimej twórczości, ale zarówno w składzie dyrekcji, jak i stałych zespołów pojawiają się już nazwiska z zewnątrz – zwłaszcza w Pradze, gdzie kierownictwo Czeskiego Baletu Narodowego od 2017 roku piastuje Filip Barankiewicz, a na czele Opery Narodowej dwa lata później stanął reżyser Per Boye Hansen, uprzedni dyrektor artystyczny Den Norske Opera w Oslo.

Właśnie taka scena narodowa – wypełniająca swą misję estetyczną, społeczną i edukacyjną, a zarazem zasilana na co dzień, nie od wielkiego dzwonu, świeżymi pomysłami wybitnych artystów i realizatorów z całego świata – marzy mi się od dawna w Polsce. Teatr, który potrafi skusić swoją ofertą także przybyszów z zagranicy i wzbudzić zainteresowanie międzynarodowej krytyki: krótko mówiąc, teatr „narodowy” w najnowocześniejszym tego słowa znaczeniu, wyzbyty kompleksów, promujący kulturę swojego kraju mądrze i skutecznie, przede wszystkim po to, żeby wprowadzić ją na stałe do światowego obiegu.

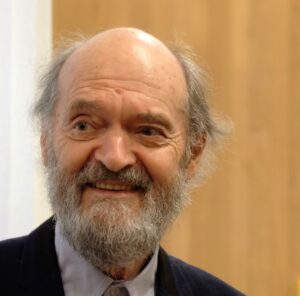

Medea w Pradze. Svetlana Aksenova w roli tytułowej i Arnheiður Eiríksdóttir (Neris). Fot. Petr Neubert

Pomarzyć zawsze sobie można, mając zarazem świadomość, że akceptacja takiego stanu rzeczy wymaga czasu i cierpliwości. Także w Pradze, gdzie poczynania norweskiej dyrekcji wciąż trafiają na opór publiczności i co bardziej konserwatywnych recenzentów. Podobnie było ze styczniową premierą Medei Cherubiniego w Teatrze Stanowym, chłodno przyjętą przez widzów, których oczekiwania wyraźnie rozminęły się z muzyczną i teatralną rzeczywistością spektaklu.

Rok temu warszawski TW-ON zaprzepaścił okazję zaprezentowania utworu w dobrze przygotowanej wersji pierwotnej. Médée – opera, a ściślej opéra comique z francuskim librettem François-Benoît Hoffmanna na motywach tragedii Eurypidesa i Corneille’a – powstała w 1797 roku i doczekała się prapremiery 13 marca w paryskim Théâtre Feydeau. Dzieło, w którym fragmenty śpiewane przepleciono ustępami recytowanymi aleksandrynem, jest wprawdzie klasyczne w formie i pod względem struktury muzycznej wyrasta z ducha reformy Glucka, niemniej w sposobie potraktowania głównej postaci wyprzedza epokę o dobre sto lat, zapowiadając wielkie operowe dramaty psychologiczne Verdiego, Wagnera, a nawet Ryszarda Straussa. Piekielnie trudna i najeżona mnóstwem pułapek technicznych partia tytułowa powstała z myślą o Julie-Angélique Scio, wybitnej sopranistce, a zarazem wielkiej aktorce, która włożyła w nią tyle serca i zapału, że podupadła na zdrowiu i wkrótce później zmarła. Warstwa orkiestrowa – bogata w nawracające motywy, gęsta, a mimo to płynna pod względem narracyjnym – przerosła możliwości percepcyjne wielu ówczesnych słuchaczy.

Nic więc dziwnego, że Médée wkrótce zeszła z afisza. I jak często w takich przypadkach bywa, zaczęto ją „ulepszać”. W 1800 roku, wystawiona w przekładzie niemieckim, zyskała całkiem przychylne przyjęcie berlińskiej publiczności. Dwa lata później dotarła do Wiednia z librettem przetłumaczonym na włoski. W 1855 roku Franz Lachner wyrzucił z niej dialogi mówione i zastąpił je iście wagnerowskimi recytatywami, posiłkując się skróconą wersją wiedeńską, ale z niemieckim librettem. W roku 1909 Carlo Zangarini przetłumaczył wersję Lachnera na włoski: z myślą o premierze w La Scali. Medea w takiej postaci – najbardziej znanej współczesnym miłośnikom opery, a zarazem żałośnie niepodobnej do pierwowzoru – została „wskrzeszona” przez Marię Callas, która po występie we Florencji w 1953 roku śpiewała ją ze zmiennym powodzeniem aż do początku lat sześćdziesiątych.

I na tę wersję zdecydowano się w Pradze, co od początku było pomysłem dość ryzykownym z uwagi na nieuchronne porównania ze sztuką wokalną Primadonny Assoluta. Przyznam szczerze, że i ja miałam wątpliwości, jak z tą morderczą partią poradzi sobie Svetlana Aksenova, którą w 2018 roku słyszałam w partii Lizy w Damie pikowej i oceniłam jej głos jako urodziwy, ale wybitnie liryczny, wręcz dziewczęcy w wyrazie. Od tamtej pory zmatowiał, stracił pewność intonacyjną i nie rozwinął się w górze skali – w miarę stabilnie brzmiał tylko w średnicy. Śpiewaczka ewidentnie porwała się na rolę, która leży poza granicą jej możliwości, a że zabrakło jej także charyzmy, wielbiciele boskiej Callas istotnie mogli poczuć się rozczarowani. Znacznie lepiej wypadła Jana Sibera (Glauce), której zmysłowy, roziskrzony sopran miałam okazję podziwiać niedawno w Kleider machen Leute Zemlinsky’ego. Błędem było powierzenie roli Kreonta Marcellowi Bakonyiemu – jego bas, niewątpliwie dobrze prowadzony, okazał się zbyt jasny i nie dość szlachetny w barwie do tej królewskiej partii. Najjaśniejszymi punktami obsady okazali się Evan LeRoy Johnson, znakomity Jazon, obdarzony dużym, dźwięcznym, typowo spintowym tenorem i godną podziwu umiejętnością dynamicznego kształtowania frazy; oraz Islandka Arnheiður Eiríksdóttir w roli Neris – dysponująca nie tylko pięknym, mieniącym się alikwotami mezzosopranem, ale i świetnym warsztatem aktorskim. Nie dziwi mnie, że publiczność doceniła pracę chóru (przygotowanie Pavel Vaněk), nie do końca rozumiem, dlaczego tak chłodno przyjęła odpowiedzialnego za całość dyrygenta Roberta Jindrę, który dołożył wszelkich starań, by z tej „zwłoszczonej” partytury wydobyć jak najwięcej elementów świadczących o niezwykłości stylu Cherubiniego – osobliwości faktury, czające się niemal w każdym takcie napięcie dramatyczne, sugestywne, zapowiadające już symfonikę Beethovena obrazy orkiestrowe, w których klasyczna spójność formy i brzmienia ustępuje czasem miejsca gorączkowym dialogom poszczególnych grup instrumentalnych.

Svetlana Aksenova i Evan LeRoy Johnson (Jazon). Fot. Petr Neubert

Praskim widzom nie spodobała się też inscenizacja, przygotowana przez niemieckiego reżysera Rolanda Schwaba we współpracy z Paulem Zollerem (scenografia), Sabine Blickenstorfer (kostiumy) i Franckiem Evinem (światła). Schwab, który w czasie pandemii uratował honor Bayreuth oszczędną i funkcjonalną koncepcją Tristana, w podobnym duchu podszedł do Medei – moim zdaniem z zaskakująco dobrym rezultatem. Zachowując klasyczną jedność czasu i miejsca, rozegrał całość na dwóch poziomach – surowego, odartego z wszelkich ozdób pałacu Kreonta, malowanego jedynie światłem wpadającym przez wysokie okna, i podgryzającego go od spodu mrocznego świata Medei – wilgotnego, pełnego czarnych worków na śmieci, tchnącego zgnilizną, która wkrótce zacznie się wdzierać także w przestrzeń korynckiej rezydencji. Z każdą kolejną sceną w pałacu robi się coraz ciemniej – aż do chwili, kiedy dom niedoszłych nowożeńców stanie w płomieniach, a Jazon wyniesie z pożaru zwęglone ciało Glauce: tak zaślepiony rozpaczą po stracie ukochanej, by całkiem zapomnieć o swoich synach i dopiero w finale dostrzec ich wiszące pod sufitem zwłoki. Nie było w tej inscenizacji ani natrętnego psychologizowania, ani prób osadzenia klasycznej tragedii w bieżącym kontekście politycznym – prosty współczesny kostium tylko się przysłużył czystości przekazu.

Ciekawe, czy spektakl z czasem okrzepnie i zyska bardziej przychylną publiczność. Moim zdaniem w pełni na to zasłużył – w porównaniu z innymi propozycjami teatru reżyserskiego koncepcje Schwaba sprawiają wrażenie wyjątkowo klarownych i przyjaznych śpiewakom. Przedstawienia opowiedziane równie oszczędnym i nowoczesnym językiem scenicznym są już od dawna codziennością w Brnie, gdzie spotykają się ze znacznie lepszym przyjęciem, zarówno ze strony widzów, jak i krytyki. Dlatego nazajutrz po praskiej premierze wybrałam się do Janáčkovego divadla na jedną z najgłośniejszych inscenizacji bieżącego sezonu: Rusałkę w reżyserii Davida Radoka, którego wcześniejsza Salome zrobiła na mnie piorunujące wrażenie.

Tym razem jednak wyszłam z teatru odrobinę skonfundowana. Po pierwsze, nie dość jasną deklaracją Radoka, że przywiózł do Brna nie tyle nową koncepcję sceniczną arcydzieła Dworzaka, ile rekonstrukcję przedstawienia, które wyreżyserował w 2012 roku w Göteborgu – w zjawiskowej urody dekoracjach Lars-Åkego Thessmanna, nawiązujących do obrazów duńskiego artysty Vilhelma Hammershøia, autora monochromatycznych, wypełnionych intymnym światłem widoków wnętrz. Radok, który w programie brneńskiego spektaklu figuruje też jako scenograf, przyznaje wprawdzie, że czerpał inspirację z dzieła Thessmanna – na scenie Janáčkovego divadla ujrzałam jednak niemal dosłowne odwzorowanie oprawy plastycznej spektaklu z Göteborgsoperan, może z wyjątkiem II aktu, gdzie Radok rozbudował scenerię w głąb, w pełni wykorzystując przestrzeń teatru w Brnie. Podobnie jest z kostiumami Zuzany Ježkovej, które odwołują się jednoznacznie do projektów Ann-Mari Anttili – owszem, czasem różnią się od nich kolorem i szczegółami kroju, zdarzało mi się jednak oglądać wznowienia legendarnych spektakli, w których kostiumografowie pozwalali sobie na znacznie dalej idące odstępstwa od pierwowzoru. Nie podejrzewam realizatorów ani dyrekcji teatru o złe intencje, wolałabym jednak, żeby tego rodzaju informacje były jasno zaznaczone w programach i na stronie internetowej – zwłaszcza że chodzi o przedstawienie, które przed laty odbiło się szerokim echem, nie tylko w wąskim światku operowym.

Rusałka w Brnie. Jan Šťáva (Wodnik) i Václava Krejčí (Ježibaba). Fot. Marek Olbrzymek

Po drugie, Radok zastosował w Brnie ten sam zabieg, co wcześniej w Göteborgu: proponując odczytanie Rusałki przez pryzmat archetypów Jungowskich i psychoanalizy Freuda, zdecydował się usunąć z dzieła wszelkie motywy ludowo-baśniowe, co w praktyce oznacza zredukowanie obsady o postaci Gajowego i Kuchcika, okrojenie partii Ježibaby i dodatkowe ingerencje w pozostały tekst. Tym samym z utworu ubyła mniej więcej jedna piąta materiału muzyczno-tekstowego. Rozumiem, gdyby reżyser pierwszy wpadł na pomysł freudowsko-ibsenowskiej Rusałki, ale realizowane w tym duchu spektakle pojawiają się na światowych scenach od blisko pół wieku, a twórcy najbardziej udanych inscenizacji – na czele z Pountneyem i McDonaldem – wykorzystali zawarty w operze „element baśniowy” z ogromną korzyścią dla swoich koncepcji. Libretto Jaroslava Kvapila czerpie przecież inspirację zarówno z baśniowo-naturalistycznych sztuk Hauptmanna, jak i z późnej, symbolistycznej twórczości Ibsena. Kvapil poruszał temat zderzenia dwóch porządków świata w swoich własnych dramatach. Był jednym z pionierów czeskiego teatru modernistycznego. Jego Rusałka, mistrzowsko skonstruowana w warstwie językowej i dramaturgicznej, jest odrębnym arcydziełem, zdradzającym pokrewieństwa z twórczością Oscara Wilde’a. Dworzak traktował ten tekst z nieomal nabożną czcią, o czym świadczy choćby jego korespondencja z Kvapilem. Radok, bądź co bądź Czech, dostrzegł w nim tylko pesymizm i dekadencję, całkowicie pomijając tak charakterystyczną dla środkowoeuropejskiego modernizmu groteskę i czarny humor.

Koncepcja Radoka znalazła wielu zwolenników, także wśród wielbicieli Rusałki. Mnie – paradoksalnie – chwilami dłużyła się ta narracja, realizowana monotonnie, na jednym poziomie emocji, bez chwil dramatycznej przeciwwagi, które u Kvapila i Dworzaka pełnią nie tylko funkcję przerywników, ale też istotnych, dopełniających kontekst komentarzy. Pod względem wizualnym jest to jednak spektakl naprawdę olśniewający – malarska opowieść o tysiącu odcieni samotności, pustki i osamotnienia, balansująca na granicy dwóch światów, które tylko pozornie się przenikają. Zwiastuny nieszczęścia kryją się wszędzie. Trzciny porastające brzegi pomostów łączących wnętrze z zewnętrzem są pożółkłe już w pierwszym akcie, izba jest pusta i szara, ale w porównaniu z aktem trzecim, gdzie resztki opadniętych źdźbeł walają się po zalanej wodą podłodze, istotnie może się wydać przytulnym schronieniem. Zamkowy ogród rozświetlają zawieszone pod czarnym niebem żyrandole, w których blasku niczego nie widać: weselni goście zdają się nie dostrzegać ani niemej rozpaczy Rusałki, ani udręki Wodnika, ani tego, co dzieje się między Księciem a Obcą Księżniczką. Radok mocno wyeksponował wagnerowskie aspekty tej opowieści: przekomarzanki leśnych nimf ze złaknionym bliskości Wodnikiem wzbudzają nieodparte skojarzenia z początkiem Złota Renu i upokorzeniem Alberyka, zimna i niedostępna Ježibaba nabiera pewnych cech Erdy, śmierć Księcia i powrót Rusałki w świat wodnej nocy przypomina finał Tristana i Izoldy.

Peter Berger (Książę) i Jana Šrejma Kačírková (Rusałka). Fot. Marek Olbrzymek

Przedstawienie było też doskonale przygotowane pod względem muzycznym. Jana Šrejma Kačírková wyśpiewała swym dźwięcznym, rozmigotanym sopranem całą nadzieję, ból i rezygnację tytułowej bohaterki. Peter Berger po raz kolejny dowiódł, że w arcytrudnej partii Księcia – bohaterskiej, ale wymagającej dużej dozy liryzmu i przede wszystkim bardzo rozległej skali – niewielu ma sobie równych na współczesnych scenach. Wspaniałym Wodnikiem okazał się Jan Šťáva – typowo „czeski” bas, imponujący głębią brzmienia, fenomenalną dykcją, lekkością frazy i przenikliwością w budowaniu tej niejednoznacznej postaci. Obdarzona pewnym, świetnie prowadzonym mezzosopranem Václava Krejčí zarysowała przekonującą sylwetkę chłodnej i pryncypialnej Ježibaby. Odrobinę mniej podobała mi się Eliška Gattringerová w partii Obcej Księżniczki, wykonanej sopranem o wolumenie godnym Brunhildy, chwilami jednak zbyt ostrym, zwłaszcza w górze skali. Niezwykłą muzykalnością wykazali się pozostali soliści: trzy Leśne Nimfy (Doubravka Novotná, Ivana Pavlů i Monika Jägerová) oraz Tadeáš Hoza (Myśliwy). Całość – wraz ze znakomitym chórem Opery NdB – poprowadził Marko Ivanović, chwilami w zbyt statecznych jak na mój gust tempach, za to z ogromną dbałością o detale tej intymnej, nieodparcie zmysłowej partytury.

Ponarzekałam sobie, pozachwycałam się i oświadczam, że to dobry znak. Za południową granicą dzieje się prawdziwy teatr operowy. Niezwykle aktywny, imponujący rozległością repertuaru, stabilnym poziomem muzycznym i odwagą w realizowaniu ambitnych przedsięwzięć, które nie zawsze kończą się pełnym sukcesem. Teatr, którego spektakli nie trzeba wstydliwie przemilczać ani chwalić na wyrost, bo na tym etapie potrafi się także zmierzyć z krytyką. Jakże mi tego brakuje na co dzień – na szczęście do Czech niedaleko.