Be This House Named Wahnfried

It’s been almost ten years and I still feel that one of the most inspiring projects I have encountered in my career as a critic was Wagner’s Ring in Karlsruhe – produced on the initiative of Peter Spuhler, the then director of the Badisches Staatstheater, by four directors, one for each part of the cycle, and complemented by a new opera, Wahnfried, commissioned especially for the occasion from the Israeli-American composer Avner Dorman. I wrote at the time that the theatre in Hermann-Levi-Platz – named after a descendant of a famous rabbinical family, Kapellmeister of the Karslruhe court opera and a great admirer of Wagner, who after many twists and turns entrusted him with the premiere of his Parsifal – would pave the theatrical way to Bayreuth for the four directors. And indeed: of the four “young and talented”, three have already reached the Green Hill, with Yuval Sharon’s Lohengrin enjoying an unprecedented return to the Festspielhaus stage this season.

There could hardly be better confirmation of the need to separate the work from its creator than the legacy of Spuhler’s directorship in Karlsruhe. His tenure – exceptionally successful in artistic terms – had a premature and turbulent ending following violent protests against his authoritarian managerial methods. Nevertheless, the four-director Ring made history and great reviews followed the premiere Wahnfried – its smallest detail honed by all the members of the creative team and artists involved, from the composer and authors of the Anglo-German libretto, Lutz Hübner and Sarah Nemitz; the conductor Justin Brown and the carefully selected cast, who included several soloists from the Ring he conducted; to the production team headed by Keith Warner.

The title of Dorman’s opera refers to the villa in Bayreuth in which Wagner spent the last years of his life and which he named Wahnfried – much to the delight of the town’s residents, who associated the word “Wahn” mainly with madness and delusion. Yet what the composer had in mind was the Schopenhauerian creative frenzy as well as refuge providing a respite from it. He probably did not anticipate that Haus Wahnfried would be transformed into a ghastly mausoleum, the seat of a degenerate cult of his person and oeuvre, a cult created by his grieving widow Cosima and her increasingly bizarre acolytes, including Houston Stewart Chamberlain, a man uprooted from his own culture, advocate of Arthur de Gobineau’s racist thought and ardent promoter of the völkisch ideology, which many believe had a fundamental impact on the development of the Nazi doctrine.

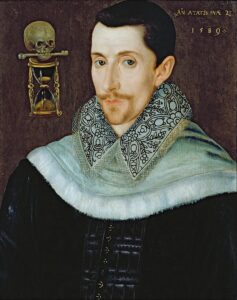

Mark Le Brocq (Houston Stewart Chamberlain). Photo: Matthew Williams-Ellis

Chamberlain is the protagonist of Dorman’s opera – in line with the intentions of the co-producers of the venture, which came at a time of historical reckoning for the Bayreuth clan, begun a few years before the bicentennial of the composer’s birth. Wahnfried was intended as something of a divertissement between the successive presentations of the Ring in Karlsruhe: a creative impression on the “dangerous liaisons” of the Wagner family, parallel to many educational initiatives at the time, like the famous “Verstummte Stimmen” exhibition, a part of which is still available on the Green Hill, and the documentary Wagner & Me, featuring the British actor, writer and Wagnerite Stephen Fry.

Wahnfried turned out to be an impression made all the more interesting by the fact that it was filtered through the experiences and sensibilities of a forty-year-old artist raised in Israel, where Wagner’s music still remains a taboo that cannot be broken even by prominent Jewish artists. This may be the reason why Dorman did not fall into the trap of Wagnerian pastiche, writing his first opera in the spirit of postmodern eclecticism – with numerous references to forms and genres of the past, a work seemingly comprising two acts, but in fact composed of a dozen separate episodes, juxtaposed to create an almost cinematic contrast of musical planes. Dorman is a very skilful polystylist. He builds the sound climate of his work – based on expressive melodic structures, and ostinato rhythms as if straight from Shostakovich – from references to jazz, salon waltzes, military marches, Weimar cabaret, individual leitmotifs from Wagner’s operas, klezmer music, and snippets of Protestant chorales. The solo parts oscillate between a declamatory style and poignant lyricism (Siegfried Wagner’s magnificent monologue at the beginning of Act Two), merging perfectly in the group scenes with the sound of the chorus and the colourful orchestral layer.

The music of Wahnfried – sophisticated yet accessible – has something irresistibly “American” about it. To many critics it brings to mind John Adams; to me it is associated more with John Corigliano and the fusion of styles typical of his oeuvre: not devoid of the grotesque and black humour, manoeuvring between realism and the world of delusion, effectively shattering convention, like in the now somewhat forgotten opera The Ghosts of Versailles. However, Dorman and his librettists too often resort to stereotypes: Chamberlain became an ardent Wagnerite as early as in the 1870s; his first visit to Wahnfried did not come until 1888, five years after the death of his beloved composer; only then did he join the Bayreuther Kreis, in which the seeds of völkisch nationalism and a new, racist strand of anti-Semitism had already been sown by Baron Hans von Wolzogen, whom Wagner himself had invited to edit the Bayreuther Blätter monthly, a decision he soon came to regret bitterly. The story of Isolde, the first fruit of Cosima and Richard’s love, who was denied her share of Wagner’s legacy, is much more tragic and multifaceted: Cosima herself lived with the stigma of being Liszt’s illegitimate child; matters were further “complicated” by her then husband Hans von Bülow, who acknowledged his paternity of Isolde. Isolde’s rejection by her mother was also influenced by the conventions of the day, which stigmatised marriages supported by the wife – and this was the case of Isolde, who married the penniless conductor Fritz Beidler. Chamberlain himself made advances to Isolde: his subsequent marriage to Eva von Bülow, Wagner’s second daughter, was the result of cold calculation. Cosima learned of Isolde’s untimely death by chance ten years after the fact – less than a year before her own death. Most importantly, however, both Cosima and Houston Stewart Chamberlain died before Hitler came to power, and the main culprit behind the dictator’s later association with Bayreuth was the naive and not very intelligent Winifred, whose actions deserve a separate opera.

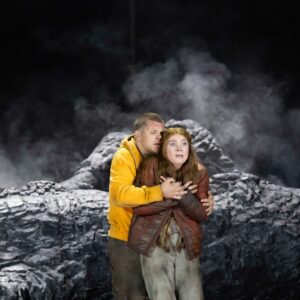

Mark Le Brocq and Oskar McCarthy (Wagner-Dämon). Photo: Matthew Williams-Ellis

The narrative oversimplifications and lack of psychological depth in Wahnfried were counterbalanced in Karlsruhe by singers who brought to mind the complex characters of the Ring. Wagner’s spectre haunting Chamberlain was played by the singer portraying the equally ambiguous character of Alberich. Hermann Levi, a man torn between his love for the composer and having to put up with his anti-Semitic taunts, was portrayed by the singer playing Wotan in the Karslruhe staging.

Polly Graham, the director of the Longborough production, followed a different path: she engaged in a dialogue with Keith Warner’s concept of the premiere, alternately arguing with it and refining the British director’s ideas. She deliberately juxtaposed Chamberlain’s grotesque figure with reality – Mark Le Brocq is much closer to the historical character than Matthias Wohlbrecht, who sang the role in Karlsruhe. Graham has preserved the vaudeville-cabaret feel of some of the episodes by casting the accomplished dancer and circus artist Tamzen Moulding as Acrobat. Wagner-Dämon – in Warner’s concept bringing to mind Jack Napier from Burton’s Batman – has been transformed into a green jester, a joker pulled from the deck in successive deals of history’s cards. The Master’s Disciple (Hitler) – made to look by the director of the premiere as the dictator from Chaplin’s film – is brought on stage as a Great War veteran, wearing a uniform decorated with a clown’s pompoms. Together with the set designer Max Johns and costume designer Anisha Fields, Graham has convincingly conveyed the ghastly atmosphere of the Bayreuth clan – manipulators controlled by Cosima, who distorted the composer’s ideas, controversial in any case from today’s point of view.

Musically, the Longborough Wahnfried was on a par with the Karlsruhe production. Special credit should go to Le Brocq for his phenomenal portrayal of Chamberlain, going far beyond the original framework of a character role. It is impossible to forget the chilling interpretation of Cosima by the seasoned Wagnerian Susan Bullock, who, approaching the end of her career, managed to turn her inevitable weaknesses into assets worthy of the world’s best stages; the superb technique of Alexandra Lowe, a singer blessed with a soprano of great beauty, expressive and secure intonation-wise, which was evident in the dual roles of Isolde and Winifred; and the touching portrayal of Siegfried Wagner by Andrew Watts, who sang the role in Karlsruhe – although his countertenor has since become dull and lost some of its harmonics, it has definitely gained in strength of expression. Excellent performances also came from the soprano Meeta Raval (as Anna and Eva, Chamberlain’s wives); Adrian Dwyer, a memorable Mime from the Ring conducted by Negus, this time in the sinister role of the Master’s Disciple; the baritone Edmund Danon, making his LFO debut (as the living and dead Hermann Levi); and Oskar McCarthy, coming from a slightly different order, in the baritone part of Wagner-Dämon. McCarthy, a versatile singer, actor and performer, more than made up for some shortcomings in his vocal technique with his theatrical craftsmanship. Another singer deserving a favourable mention is the Cuban-French bass-baritone Antoin Herrera-López Kessel as Kaiser Wilhelm II and the anarchist Bakunin. I was not disappointed either by the chorus, larger than usual for this company, augmented by members of the Longborough Community Chorus. The whole thing was conducted by Justin Brown, repeating his Karlsruhe success and once again showing the LFO regulars that he is not only an effective conductor, but primarily a very sensitive musician.

Adrian Dwyer (Master’s Disciple). Photo: Matthew Williams-Ellis

The British premiere of Wahnfried, which was met with favourable reception from both the critics and the audience, despite the work’s shortcomings, proved to be an important and necessary venture. All the more important given that it was undertaken by LFO, a company established out of pure and disinterested love for Wagner, demonstrating again and again that it cares for his legacy more wisely than his Bayreuth heirs, who often go astray. That is why I am surprised by some voices claiming that staging Dorman’s opera in the “English Bayreuth” was a reckless act, an initiative fraught with the risk of undermining the achievements of the rural opera company from Gloucestershire. That is why I was alarmed by the essay included in the programme, the author of which, Michael Spitzer – perhaps with the best of intentions – engaged in manipulation in the other direction. The world is once again plunging into the hell of hypocrisy; ideologies that were supposed to be gone forever after Hitler’s defeat are on the rise again. So it is better not to repeat the long-discredited legend about the porcelain monkeys of Moses Mendelssohn, grandfather of the composer Felix – a humiliating purchase the philosopher had to make to be granted permission to marry. Spitzer repeats the hackneyed cliché that the figurines in Mendelssohn’s collection are an example of the so-called Judenporzellan, items purchased by Jews under duress in exchange for the right to start a family and have legitimate offspring. True, Frederick the Great did promulgate this disgraceful decree – one of many intended to boost sales of products from his Berlin manufactory – but not until 1769, when Moses had long been married. Not only that – six years earlier the same Frederick had granted Moses the Schutzjude status, protecting the scholar from the persecution that indeed affected his poorer and less privileged brethren, that is, practically most of the Jewish community in Prussia. However hideous the figures in the Mendelssohn collection may seem today, in Moses’ times they were regarded as a symbol of luxury and affluence. Therefore, Felix could have not treated the heirlooms inherited from his grandfather as a “racist memento mori”. The whole story is an anachronistic construct rejected by researchers almost half a century ago.

This does not mean that there was no anti-Semitism in Germany in Wagner’s days. This does not mean that Wagner was not an anti-Semite. Finally, this does not mean that Chamberlain did not pour racist poison into this leaven – with disastrous consequences, as we increasingly tend to forget. History must not be manipulated to introduce audiences to Dorman’s work. It is necessary to seek the truth and truth does not lie in the middle at all. “The truth lies where it lies”, as Władysław Bartoszewski, a member of the Żegota presidium and a Righteous Among the Nations, used to say. He was a man who understood perfectly the meaning of the phrase “to do more harm than good”.

Translated by: Anna Kijak