Zatapiając obrzędy dawnej niewinności

„Istnieje atmosfera zawieszonej w powietrzu zagadkowości, czegoś niewidzialnego, a przecież możliwego do zobaczenia innym wzrokiem, którym obdarzeni są jedynie wtajemniczeni? Istnieje na pewno, wiem o tym od pisarzy usiłujących opisać «inny wzrok», wrażliwych nań w sposób wyjątkowy, jak choćby Henry James w Obrocie śruby” – zastanawia się narrator Cmentarza Południa, „opowiadania otwartego” Gustawa Herlinga-Grudzińskiego, który właśnie w tym tekście z 1991 roku zaproponował nową polską wersję tytułu noweli Henry’ego Jamesa The Turn of the Screw. W porównaniu z tym prostym rozwiązaniem inne tłumaczenia, klasyczne W kleszczach lęku Witolda Pospieszały z 1959 roku i Dokręcanie śruby Jacka Dehnela z roku 2015, wydają się mniej fortunne. Pierwsze trąci horrorem klasy B, choć w gruncie rzeczy oddaje nastrój Jamesowskiej prozy. Drugie jest mylące, przywołuje bowiem skojarzenia z zadomowionym w polszczyźnie idiomem, który oznacza zwiększenie presji bądź rygorów. Do propozycji Herlinga-Grudzińskiego, którą wkrótce potem podchwycił też Piotr Kamiński, wróciła Barbara Kopeć-Umiastowska, w przekładzie opublikowanym między innymi przez PIW w zbiorze Historie drobnoziarniste (2019).

Trudno orzec, czy to wersja ostateczna, pozwoliła jednak tłumaczce w miarę dosłownie oddać wyjaśnienie narratora, które pojawiają się na samym początku noweli: „Zgadzam się w zupełności (…), że nawiedzenie małego chłopca, dziecka w tak niedojrzałym wieku, nadaje owej historii szczególny wyraz. Lecz nie po raz pierwszy słyszę o tego rodzaju uroczym zdarzeniu z udziałem dziecka. Jeżeli jedno dziecko przykręca śrubę efektu o kolejny obrót, to co powiecie na d w ó j k ę dzieci…? Powiemy oczywiście – zawołał ktoś – że dwoje dzieci to dwa obroty! A także, że chcemy o tym usłyszeć!”.

Wyjaśnienie to nie wyjaśnia jednak wszystkiego. Tytuł noweli Jamesa jest bowiem równie otwarty, jak ona sama. Po pierwsze chodzi o wzniesienie narracji na wyższy poziom, o niespodziewany obrót spraw, który straszną opowieść uczyni jeszcze straszniejszą – co trafnie, choć niezbyt zręcznie uchwycił w swej adaptacji Pospieszała. Po drugie, o nieubłaganą machinę opowieści, która z każdym obrotem śruby, niczym w dawnym narzędziu tortur, potęguje cierpienie ofiary i stawia ją w coraz rozpaczliwszej sytuacji – na co zapewne zwrócił uwagę Dehnel, gubiąc jednak po drodze wieloznaczność tytułu. Trudno też oprzeć się wrażeniu, że operatorem tej przerażającej machiny był sam Henry James, a instrukcję jej obsługi zabrał ze sobą do grobu, o czym świadczą niezliczone, często wzajemnie sprzeczne interpretacje noweli. Autor osiągnął swój cel – przeraził czytelnika i nie przyniósł mu ulgi w postaci logicznej i racjonalnej wykładni opisanych przez siebie zdarzeń.

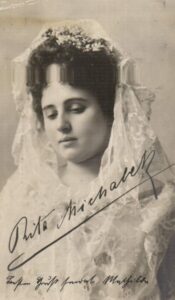

Peter Pears i Benjamin Britten przed Crag House, domem kompozytora w Aldeburghu, rok 1954

Niewykluczone, że kluczem do zrozumienia The Turn of the Screw jest to, co w noweli nie zostało opisane ani wypowiedziane. Bez tego nie sposób rozstrzygnąć, czy mamy do czynienia z opowieścią grozy, czy też szerszą metaforą. A jeśli metaforą, to czego? Szaleństwa? Potrzeby kontroli? Seksualnej frustracji? Czy duchy istnieją „naprawdę”, czy są tylko wytworem neurotycznej wyobraźni bohaterów? Czy Quint i Miles to dwa oblicza tej samej postaci? Czy panna Jessel jest tożsama z Florą? Henry James sugeruje we wstępie, że największą zaletą tej historii jest możliwość przedstawienia świata, w którym prawdziwe są tylko nasze wyobrażenia. Czytelnicy sięgają po arcydzieło Jamesa od przeszło stu lat. Żeby je wreszcie pojąć i przestać się bać, albo przeciwnie – by zgubić się na dobre w labiryncie zdarzeń i odurzyć ich grozą jak narkotykiem.

Britten potrzebował silnego impulsu do działania po lodowatym przyjęciu Gloriany w 1953 roku, zwłaszcza że mniej więcej w tym samym czasie otrzymał zamówienie na nową operę od Biennale w Wenecji. Temat, jak później wyznał, „najbliższy jego sercu”, wybrał wspólnie z Myfanwy Piper, żoną swego długoletniego przyjaciela, malarza, grafika i scenografa Johna Pipera. Tak zaczęła się ich współpraca, która zaowocowała jeszcze jedną adaptacją prozy Jamesa (Owen Wingrave) i osiągnęła kulminację w ostatnim arcydziele operowym Brittena, Śmierci w Wenecji.

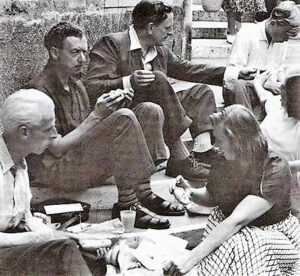

John Piper, Britten, Pears, David Hemmings, Olive Dyer i Myfanwy Piper w przerwie prób do weneckiej prapremiery The Turn of the Screw. Fot. Erich Auerbach

Libretto – konsultowane z Piper głównie przez telefon – oraz partytura The Turn of the Screw powstały w rekordowo krótkim czasie. Premiera na deskach weneckiej La Fenice odbyła się 14 września 1954 roku pod batutą kompozytora i zakończyła ogromnym sukcesem, do którego niewątpliwie przyczynił się fenomenalny odtwórca roli Milesa: trzynastoletni sopranista David Hemmings, ulubieniec Brittena od czasu występu w partii tytułowej na prapremierze Małego kominiarczyka, potem zaś jedna z ikon światowego kina, aktor znany między innymi z Powiększenia Antonioniego i Szarży lekkiej brygady Richardsona. Za tryumfem w Wenecji poszła październikowa inscenizacja w londyńskiej Sadler’s Wells Opera. Trzy lata później The Turn of the Screw dotarł za Ocean, dziś jest najczęściej wystawianą operą anglojęzyczną po Dydonie i Eneaszu Purcella.

Nie była to ani pierwsza, ani ostatnia adaptacja sceniczna noweli Jamesa. Cztery lata przed premierą utworu Brittena jednym z większych wydarzeń nowojorskiego sezonu okazała się sztuka The Innocents Williama Archibalda, która z czasem doczekała się wersji filmowej. Nikomu jednak nie udało się tak skutecznie oddać towarzyszącej noweli atmosfery strachu, niepewności i utraty poczucia bezpieczeństwa, jak uczynili to Piper z Brittenem – i to mimo licznych odstępstw od pierwowzoru, nie wspominając już o oczywistej konieczności „dopowiedzenia” pewnych wątków, które w prozie czytanej mogą pozostać otwarte. Troje narratorów z oryginału zastąpił jeden, pokrótce wprowadzający słuchaczy w akcję w Prologu (pierwszym wykonawcą tej tenorowej partii był Peter Pears). Zjawy przemówiły w operze głosem nieobecnym w noweli (dotyczy to między innymi złowieszczego dialogu Quinta i panny Jessel na początku II aktu). Zaadaptowany i rozbudowany tekst Jamesa librecistka uzupełniła materiałem zaczerpniętym z innych źródeł: słowami piosenek dziecięcych; mnemotechnicznym wierszykiem do nauki gramatyki łacińskiej, który staje się podstawą onirycznej, rozdzierającej serce arii-piosenki Milesa; nawracającą frazą o zatapianiu obrzędów dawnej niewinności, zaczerpniętą z wiersza Drugie przyjście Williama Butlera Yeatsa.

Peter Pears (Quint) i David Hemmings (Miles). La Fenice, 14 września 1954. Fot. Corbis

Główną dźwignią mechanizmu śrubowego, który raz po raz wznosi odbiorców na coraz wyższy poziom grozy, jest jednak muzyka Brittena, który mimo niewielkiej obsady dzieła (siedmioro śpiewaków i trzynastoosobowy zespół instrumentalny) stworzył jedną z najbardziej skomplikowanych partytur w swoim dorobku. Fundamentem całości jest dwunastodźwiękowy temat śruby, który pojawia się po raz pierwszy w Prologu, po czym w kolejnych piętnastu wariacjach sugeruje jej bezlitosne obroty. Wtedy właśnie wychodzi na jaw złudne podobieństwo tematu do szeregu dodekafonicznego: w rzeczywistości każda wariacja dąży w stronę określonego centrum tonalnego. Nastrój grozy potęgują mistrzowsko wykorzystane walory kolorystyczne instrumentów: rożka angielskiego w upiornej piosence Milesa, celesty skojarzonej z demonicznym Quintem, widmowej harfy, łkającej w tle ostatniej rozmowy Guwernantki z panią Grose. To właśnie Guwernantka okazuje się najlepiej skonstruowaną i najgłębszą psychologicznie spośród wszystkich postaci kobiecych w operach Brittena, a jej kołysanka dla martwego Milesa, w której rozpacz walczy o lepsze z wyrzutami sumienia, kończy dzieło akcentem bodaj dobitniejszym niż finałowy monolog kapitana Vere’a z Billy’ego Budda.

„Młodziutki bohater Obrotu śruby umiera co prawda w ramionach guwernantki, ale to nie jest epilog opowiadania. Pozostaje w nim dalej coś, czego nie da się (i nie trzeba) zdefiniować, coś nieskończonego, niedomkniętego na zawsze”, pisał Herling-Grudziński o noweli Jamesa. Niedomknięte, otwarte na zawsze pozostaje też arcydzieło Brittena, a z jakiej przyczyny, tego nie da się zdefiniować. I na szczęście nie trzeba.